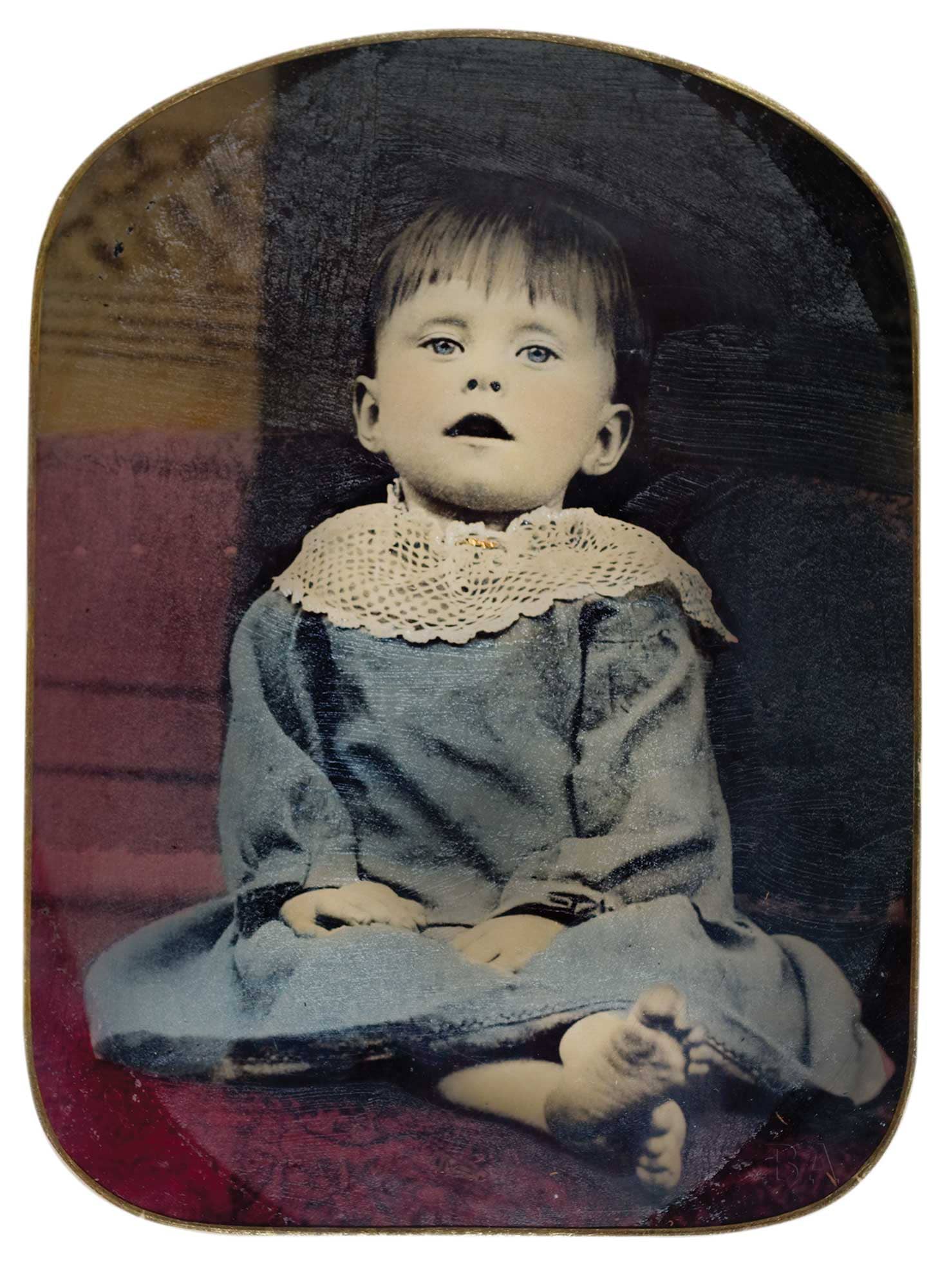

You’ve seen the photos. Those eerie, sepia-toned images on Pinterest or Reddit where a Victorian child looks just a little too stiff, or a woman stares into the camera with eyes that seem... off. The caption usually screams something about how Victorians loved propping up their dead and painting eyes on their eyelids to make them look alive.

Honestly? Most of that is total nonsense.

The internet has turned post mortem photography victoria into a gothic horror show, but the reality was much more tender. It was about grief, not ghouls. In a time when scarlet fever or consumption could wipe out half a nursery in a week, a photograph wasn't a creepy hobby. It was often the only proof that a person had ever existed.

The "Standing Dead" Myth

Let’s tackle the biggest lie first. You will see countless articles claiming those iron posing stands (the ones with the heavy bases and vertical poles) were used to hold up corpses.

Think about that for two seconds.

A human body in rigor mortis is stiff as a board, and a body past that stage is essentially dead weight. An adjustable, skinny metal rod meant to help a living person keep their head still for a 30-second exposure is not going to support a 150-pound adult. If you tried to lean a body against one of those, it would just slide right off or topple the whole thing over.

📖 Related: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

Experts like Mike Zohn and various historians from the Burns Archive have been trying to debunk this for years. Those stands were for the living. Because early camera shutter speeds were so slow, even a slight breath could blur your face. The "still" person in the photo is the one who is breathing. The person who is perfectly sharp? Well, they aren't moving because they can't.

Why the Obsession with "The Last Sleep"?

Victorians didn't want their loved ones to look like zombies. They wanted them to look peaceful. This led to the "Last Sleep" style of post mortem photography victoria.

The deceased was usually laid out on a sofa or a bed, tucked in with flowers, looking like they were just napping. It was a way to domesticate death. Since most people died at home back then—not in sterile hospital wings—death was a part of the household furniture.

- Infants: They were often cradled by their mothers.

- Children: Posed with favorite toys, like a hoop or a doll.

- Adults: Usually shown in "repose" in their Sunday best.

There are some cases where photographers tried to mimic life. They might tint the cheeks pink on a daguerreotype to hide the pallor of death. Sometimes they did paint eyes on the final print, but it wasn't some weird occult ritual. It was a desperate attempt by a parent to see their child's eyes one last time.

It Was a Luxury, Then a Commodity

Photography wasn't cheap in the 1840s. A daguerreotype could cost a week's wages for a laborer. Because of that, many families never bothered to get a portrait of their children while they were healthy. Why spend the money when the kid might not make it to age five?

👉 See also: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

But when death finally came, the panic set in.

The realization that you were about to bury your child and you had no way to remember their face—that’s what drove the market for post mortem photography victoria. It was the "last chance" portrait.

By the 1860s, with the invention of the carte de visite (basically small, paper-mounted photos), the price dropped. You could order dozens of copies and mail them to relatives. It sounds morbid to us to send a "death photo" in the mail, but to a grandmother three towns away who never met the baby, it was a precious gift.

Spotting the Real Deal

If you’re looking at an old photo and trying to figure out if it’s an actual memorial portrait, look for these clues:

- The Coffin: By the late Victorian era, the "living" poses went out of style. Most photos started showing the person in a casket. If there’s a casket, it’s definitely a post mortem.

- The Eyes: If the eyes are open and look glassy or bulging, it might be a death photo. But more often than not, it’s just a living person who blinked or had blue eyes that didn't react well to the chemicals.

- The Setting: Real death photos were almost always taken at home. Studio portraits of "dead" people are extremely rare because hauling a body to a photography studio was a logistical nightmare.

The "Hidden Mother" photos are another thing people confuse. That’s where a mother is covered in a rug or cloth to hold a squirming (living!) baby still. People love to say the baby is dead. No. If the baby was dead, it wouldn't be squirming, and you wouldn't need a mother hidden under a rug to hold it.

✨ Don't miss: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

The Cultural Shift

So why did we stop doing this?

By the early 20th century, the funeral industry started to take over. Death moved from the parlor to the "funeral parlor." We became more removed from the physical reality of dying. What was once a loving tribute started to feel "creepy" as society grew more death-phobic.

Also, Kodak happened. Once everyone had a Brownie camera and a shoebox full of snapshots of their kids playing in the yard, there was no need for a "last chance" photo. The memory was already captured.

Actionable Insights for Collectors and Historians

If you are interested in the history of post mortem photography victoria, don't just trust social media captions.

- Check the provenance: Real memorial photos often have notes on the back—names, dates, and sometimes a lock of hair tucked into the frame.

- Study the chemistry: Daguerreotypes (metal) and Ambrotypes (glass) are earlier and more likely to feature the "lifelike" poses. Later paper prints (Cabinet Cards) usually show the casket.

- Consult the pros: Look at the work of Stanley B. Burns or the archives at the Missouri Historical Society. They have the largest collections of authentic memorial photography in the world.

The next time you see one of these photos, try to look past the "spooky" filter our modern brains put on it. Imagine you’re a parent in 1870. You’ve just lost your daughter. This little piece of glass is the only thing you have left of her. It wasn't about the macabre—it was about the love that stays behind when the breathing stops.

Next Steps for You

- Verify your sources: If you're researching a specific image, use a reverse image search to see if it has been debunked by historians.

- Visit a museum: Many local history museums have Victorian mourning collections that include authentic photos you can see in person.

- Read the literature: Pick up "Sleeping Beauty: Memorial Photography in America" by Stanley B. Burns for the most accurate visual history of the practice.