You’ve probably seen those glossy magazine photos where a thick, bone-in chop sits under a glistening amber glaze. It looks easy. It looks like autumn on a plate. But then you try making pork chops with apple butter at home and things go south fast. Maybe the pork is dry as a desert. Or maybe—and this is the most common crime—the apple butter burns into a black, acrid crust before the meat is even warm in the middle.

It’s frustrating.

✨ Don't miss: Air Fryer Brussels Sprouts Recipes: Why Your Veggies Are Soggier Than They Should Be

The truth is that sugar is both your best friend and your worst enemy in the kitchen. Apple butter is packed with it. We’re talking concentrated fruit sugars and often added granulated sugar or cider. When that hits a screaming hot cast iron skillet, it doesn't just caramelize; it carbonizes. To get this right, you have to understand the thermal relationship between fruit pectin and muscle fiber.

Honestly, most people treat the apple butter like a marinade. That’s a mistake. If you soak a raw chop in apple butter and then toss it in a pan, you’re basically asking for a kitchen full of smoke.

The Science of the Sear and the Sugar

Pork is lean. Modern farming has actually made pork much leaner than it was forty years ago, which means there is very little intramuscular fat (marbling) to protect the meat from drying out. When you add a high-sugar component like apple butter, you're dealing with two different cooking temperatures. The meat needs to reach an internal temperature of about 145°F ($63^\circ C$) to be safe and juicy, according to USDA guidelines. However, the sugars in the apple butter start to burn at around 350°F ($177^\circ C$).

If you're searing in a pan that's 450°F ($232^\circ C$), that apple butter is toast before the pork is even close to done.

You need a strategy. I usually recommend the "hard sear, late glaze" method. You season the pork with just salt and pepper first. Get that Maillard reaction—the browning of the proteins—without the interference of the fruit sugar. Only in the last two minutes of cooking do you introduce the apple butter. This allows the butter to melt, emulsify with the pan juices (fond), and create a lacquered finish that sticks to the meat rather than burning onto the pan.

Why Quality Apple Butter Matters

Don't just grab the cheapest jar on the shelf. A lot of mass-produced apple butters are basically just applesauce with brown food coloring and a ton of high-fructose corn syrup. You want something thick. If you tip the jar and it runs like water, it's not going to cling to your pork chops. Look for brands that list "apples, cider, spices" as the primary ingredients.

Some people, like the folks over at Serious Eats, argue that making your own is the only way to control the acidity. They aren't wrong. A hit of apple cider vinegar or lemon juice in the butter helps cut through the heaviness of the pork fat. It balances the palate.

Choosing the Right Cut

Not all chops are created equal. You have the choice between boneless and bone-in. Choose the bone. Always. The bone acts as an insulator, slowing down the cooking process near the center and keeping that section of the meat tender while the exterior develops a crust.

Thickness is your second variable. A thin, half-inch chop is nearly impossible to cook perfectly with a glaze. By the time you’ve got a sear, the inside is overcooked. You want "Double-Cut" chops—roughly 1.5 inches thick. This gives you a massive margin for error.

- Center-Cut Loin Chops: These look like T-bone steaks. You get a bit of the loin and a bit of the tenderloin. They are lean and require a gentle hand.

- Rib Chops: These have more fat. Fat equals flavor. Fat also buys you time.

If you're at a local butcher, ask for "heritage breed" pork like Berkshire or Duroc. These breeds haven't had the fat bred out of them for the "other white meat" marketing campaigns of the 90s. They actually taste like pork.

✨ Don't miss: 1 libra a kg: Why Your Kitchen Scale Might Be Lying to You

The Maillard Reaction vs. Caramelization

It’s easy to confuse these two. Maillard is the reaction between amino acids and reducing sugars that happens when you brown meat. Caramelization is the oxidation of sugar. When making pork chops with apple butter, you are trying to bridge these two chemical processes.

If you put the apple butter on too early, the water content in the butter creates steam. Steam is the enemy of a sear. You’ll end up with grey, boiled-looking meat that has a sticky, burnt coating. Gross. Instead, sear the meat until it's about 10 degrees away from your target temperature, then pull the pan off the heat. Add the apple butter, a splash of bourbon or chicken stock to deglaze, and a knob of cold butter. Swirl it. The residual heat will finish the pork and create a sauce that looks like liquid gold.

Common Misconceptions About Fruit and Meat

A lot of people think fruit sauces are just for "fancy" dinners or the holidays. That's a bit of a myth. In reality, acidity and sugar have been used to preserve and complement fatty meats for centuries. Think about applesauce with latkes or cranberry sauce with turkey. The malic acid in apples specifically helps break down the perception of "greasiness" on the tongue.

There's also this weird idea that you have to use "sweet" apples. Actually, a tart apple butter made from Granny Smith or Braeburn apples provides a much better contrast to the savory pork. If your apple butter is too sweet, stir in a teaspoon of Dijon mustard. It sounds weird, but the mustard acts as an emulsifier and adds a spicy back-note that makes the whole dish taste more "adult."

The Equipment Factor

You need a heavy-bottomed pan. Stainless steel or cast iron. Non-stick pans are for eggs. They can't handle the high heat required to get a proper crust on a pork chop, and they certainly won't help you build a "fond"—those little brown bits stuck to the bottom of the pan that make the best sauces.

I’ve seen people try to do this on a sheet pan in the oven. It works, sorta, but you miss out on the textural contrast. If you must use an oven, sear them on the stovetop first, then move the whole pan into a 375°F ($190^\circ C$) oven to finish. This is the "sear-roasting" technique used by professional chefs like Gordon Ramsay and Thomas Keller.

A Simple Strategy for Success

Start by patting your pork chops bone-dry with paper towels. Moisture is the enemy of the sear. Season them aggressively with kosher salt. Let them sit for 15 minutes. This creates a mini-brine on the surface.

🔗 Read more: Why Bright Air Odor Eliminator Actually Works When Others Just Smell Like Cheap Perfume

Heat your oil until it just starts to shimmer. Lay the chops in, moving them away from you so you don't get splashed with hot fat. Don't touch them. Let them sit for 3 to 4 minutes until they release easily from the pan. Flip them.

Now, here is the secret.

Take a half-cup of apple butter. Mix it with a tablespoon of apple cider vinegar and maybe a pinch of red pepper flakes. Once the second side of the pork has been searing for about 3 minutes, spoon this mixture over the top of each chop. Toss in a sprig of rosemary or sage if you're feeling fancy.

Turn the heat down to medium-low. Flip the chops one more time—glaze side down—for just 30 seconds. This "sets" the glaze. Flip them back over, remove from the pan, and let them rest.

Why You Must Rest Your Meat

I cannot stress this enough. If you cut into that pork chop the second it leaves the pan, all those beautiful juices you worked so hard to keep inside will run out onto the plate. You’ll be left with a piece of dry wood.

Wait five minutes. The muscle fibers, which tightened up during cooking, will relax and reabsorb the moisture. This is when the apple butter glaze thickens and really adheres to the crust.

Elevating the Dish

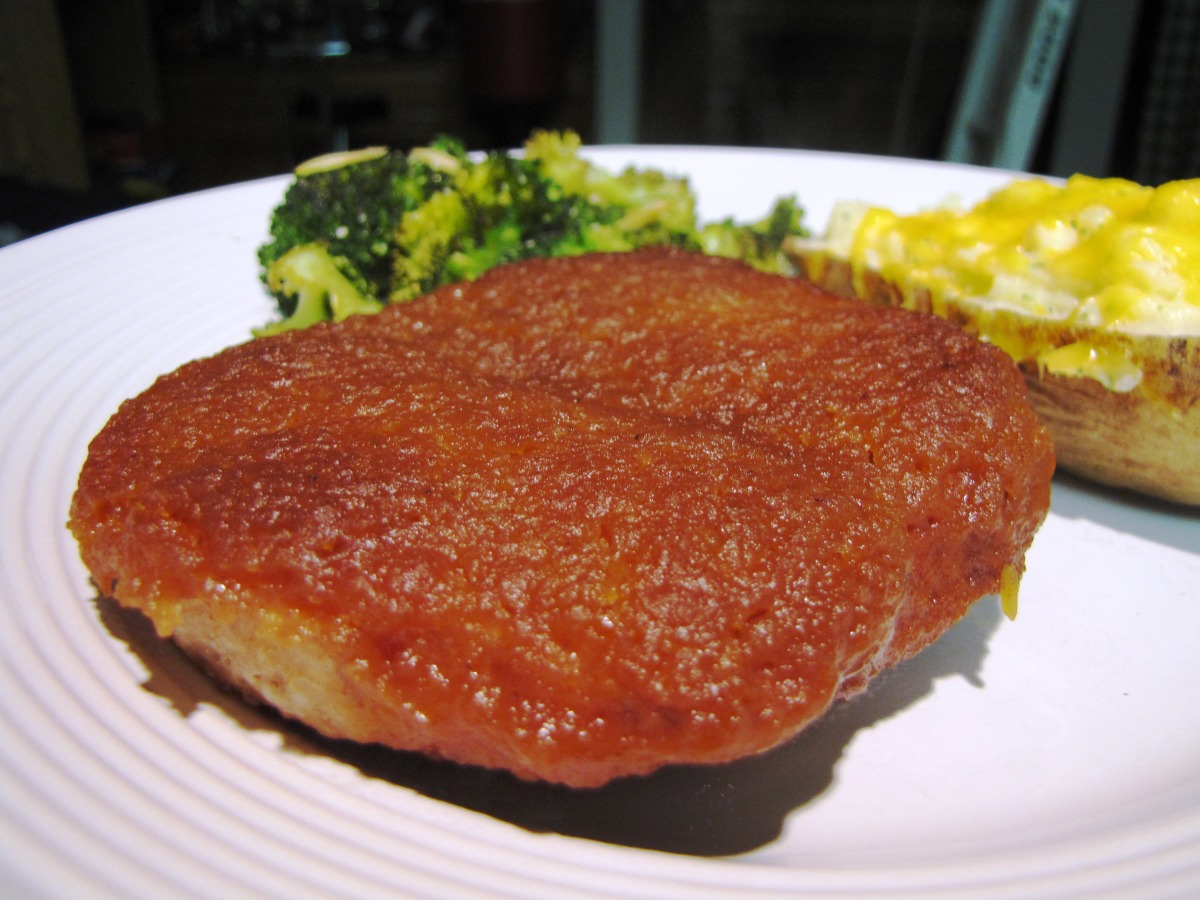

If you want to take your pork chops with apple butter to the next level, think about your sides. You need something to soak up the extra sauce but also something to provide crunch.

- Polenta or Grits: The creamy texture is a perfect foil for the sticky glaze.

- Roasted Brussels Sprouts: The bitterness of charred sprouts balances the sweetness of the apple.

- Crispy Sage: Fry a few sage leaves in the pork fat before you plate. It adds a professional touch and a concentrated herbal punch.

Some people add toasted walnuts or pecans at the very end. The earthiness of the nuts works exceptionally well with the "harvest" flavor profile of the apple butter.

Addressing the "Pink" Fear

For a long time, people were told to cook pork until it was white and chalky. This was due to fears of trichinosis. However, modern agricultural standards in the US have virtually eliminated this risk in commercial pork. A little bit of pink in the middle of your pork chop is not only safe but preferred. Aim for a rosy medium. It will be significantly more tender and will carry the flavor of the apple butter much better than an overcooked grey chop.

Final Practical Steps

To master this dish today, start by checking your pantry. Ensure your apple butter isn't expired and hasn't separated. If it has, give it a vigorous whisk before using.

- Procurement: Buy bone-in chops at least 1 inch thick.

- Prep: Salt the meat early; let it reach room temperature for 20 minutes before cooking to ensure even heat penetration.

- Execution: Use the "late glaze" technique to avoid burning the sugars.

- Acidity: Always check the balance; if the sauce tastes one-dimensional, add a drop of vinegar or a squeeze of lemon.

- Monitoring: Use an instant-read thermometer. Pull the pork at 140°F ($60^\circ C$); the carry-over heat will bring it to the perfect 145°F ($63^\circ C$) while it rests.

The difference between a mediocre meal and a restaurant-quality dinner is often just a matter of timing and temperature management. By treating the apple butter as a finishing element rather than a cooking medium, you preserve the bright fruit flavors and avoid the bitter notes of burnt sugar. This approach transforms a simple weeknight staple into a sophisticated, balanced plate.