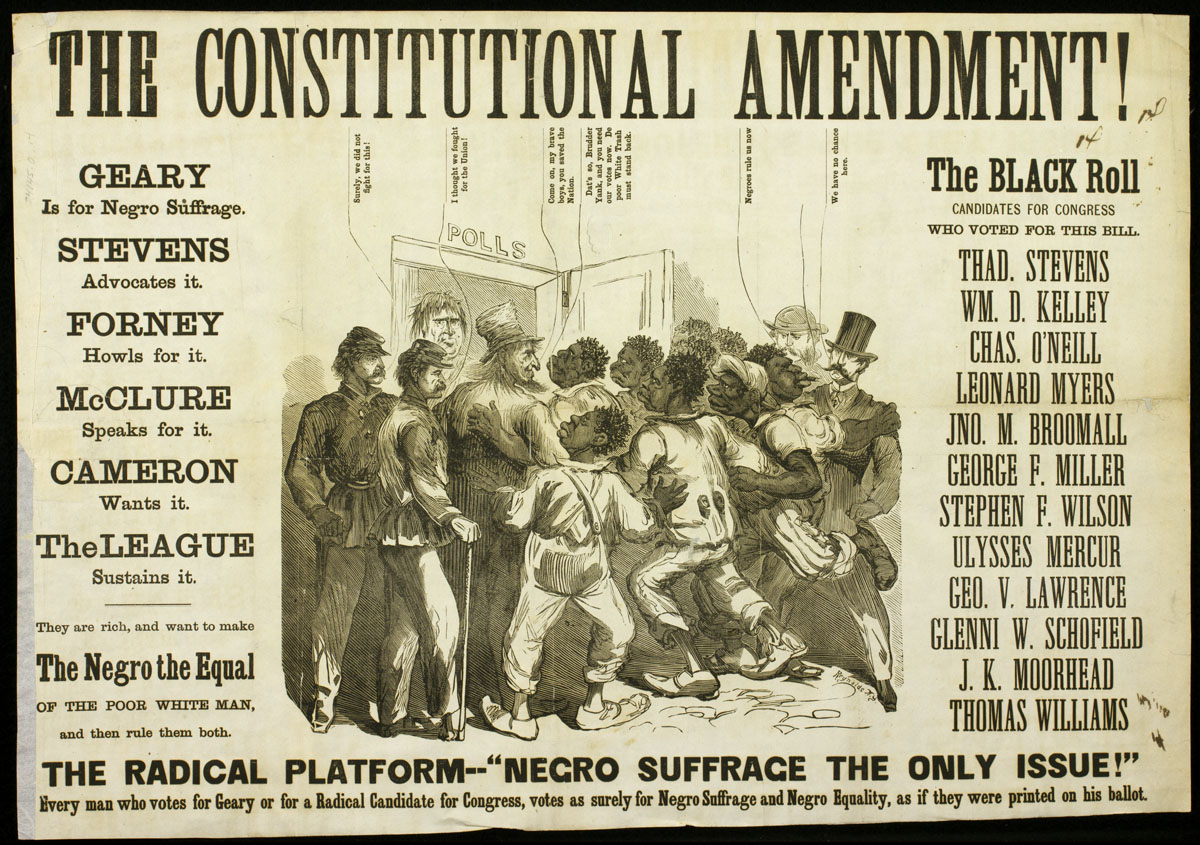

You’ve seen them in history textbooks or flickering across a screen during a cable news segment on constitutional crises. Those scratchy, ink-heavy drawings from the 1800s—or maybe the sharp, digital satires of today. Honestly, a political cartoon 14th amendment focus is usually about one thing: the massive gap between what the law says and what actually happens on the ground.

It's kinda wild when you think about it. The 14th Amendment is the "Big One." It’s the bedrock of birthright citizenship, due process, and equal protection. But since its ratification in 1868, artists have used it as a weapon to mock, defend, or expose the messy reality of American democracy.

✨ Don't miss: Are They Doing a Recount? What’s Actually Happening with Election Audits Right Now

The Thomas Nast Era: Drawing a New Republic

If you want to understand how the 14th Amendment first hit the public consciousness, you have to look at Thomas Nast. People call him the father of American political cartooning for a reason. He didn't just draw funny pictures; he basically invented the visual language of the Republican Party (the elephant) and the Democratic Party (the donkey).

Nast was a true believer in the Reconstruction Amendments. In his famous 1869 piece, “Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner,” he captures the idealistic hope of the era. You see a massive table where people of all races—Black, White, Chinese, Native American—sit as equals. On the wall, portraits of Lincoln and Grant hang near the words "Universal Suffrage."

This wasn't just a "nice" picture. It was a radical political statement. By including the phrase "Free and Equal" alongside images of diverse families, Nast was visually translating the Equal Protection Clause for a public that was still incredibly divided.

When the Tone Shifted

But hope doesn't always last. By 1874, Nast’s work got darker. His cartoon “The Union As It Was” is haunting. It shows a member of the White League shaking hands with a KKK member over a cowering Black family. The shield between them says "The Lost Cause."

This is where the political cartoon 14th amendment narrative gets real. The drawing isn't about the law itself, but about the failure to enforce it. It mocks the idea that the "Union" was restored when, in reality, the 14th Amendment was being systematically dismantled by domestic terrorism and Supreme Court rulings that narrowed its scope.

✨ Don't miss: East Bay Earthquake Today: Why San Ramon Keeps Shaking

Section 2 and the Sleeping Giant

Most people focus on the first section of the 14th Amendment—the "all persons born or naturalized" part. But cartoonists have a weird obsession with Section 2, which is basically the "penalty clause." It says that if a state denies the right to vote to its citizens, that state should lose some of its seats in Congress.

Basically, it's a "use it or lose it" rule for political power.

There’s this famous 1902 drawing by E.W. Kemble. It shows Congress as a giant, bloated man sleeping in a hammock labeled "Law Enforcement." At his feet lies a broken gun labeled "14th Amendment, 2nd Section." A small child walks by with a drum, but the GOP elephant whispers, “Don’t wake him up!”

It’s a brutal critique. It shows that even forty years after the Civil War, the government was perfectly happy to ignore the 14th Amendment’s teeth to keep the peace with Southern legislators.

The Modern Revival: Insurrection and Section 3

Fast forward to the 2020s. Suddenly, everyone is talking about Section 3. This is the "Insurrectionist Clause." It bars anyone from holding office if they’ve previously taken an oath to the Constitution and then engaged in "insurrection or rebellion."

Modern cartoonists like Patrick Chappatte or Matt Wuerker have had a field day with this. You’ll see images of the Constitution being used as a literal gate to block candidates, or the 14th Amendment depicted as an old, dusty "In Case of Emergency" glass box that’s finally being smashed open.

The debate in these cartoons usually centers on whether the amendment is a self-executing "shield" for democracy or a "weapon" being used for lawfare. Sorta depends on which side of the aisle the artist sits on.

Why These Drawings Actually Matter

Why do we care about a political cartoon 14th amendment archive? Because law is dry. The 14th Amendment is a wall of text that can be hard to parse. Cartoons do something the law can't: they show the human stakes.

- Simplification: They take a complex concept like "Privileges or Immunities" and turn it into a physical object—a ballot, a home, a seat at a table.

- Hypocrisy: They are the ultimate "receipts." When a politician claims to support the Constitution while undermining the 14th, a cartoonist is there to draw them literally stepping on the document.

- Emotional Weight: A cartoon of a Black veteran being denied a vote (like Nast’s 1866 “Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction”) hits harder than a 50-page legal brief.

How to Analyze a 14th Amendment Cartoon

If you’re looking at one of these for a class or just out of curiosity, don't just look at the middle. Look at the corners.

1. Check the date. A cartoon from 1868 (ratification) looks very different from one in 1896 (the year Plessy v. Ferguson essentially gutted the amendment).

2. Identify the symbols.

- Columbia: Usually represents the "soul" or "ideal" of America.

- Uncle Sam: Represents the government or the law.

- The Shield: Often represents the protections of the Constitution.

3. Look for the "But."

Most 14th Amendment cartoons have a "But." As in, "The law says X, but the reality is Y." Find the Y, and you’ve found the artist's message.

Actionable Next Steps for Enthusiasts

If you want to go deeper into this, don't just Google "funny 14th amendment pictures." Use real archives.

First, head over to the Library of Congress digital collections. Search for "Reconstruction political cartoons." You'll find high-res scans of original Harpers Weekly pages where you can see the ink bleeds. It's much more visceral than a grainy thumbnail.

📖 Related: What Really Happened with the Bowling Green Tornado 2021

Second, compare a historical cartoon with a modern one. Find a drawing from the Civil Rights Movement—like the ones about Brown v. Board of Education—and put it next to a 2024 cartoon about Section 3. You’ll notice that while the faces change, the arguments about "states' rights" versus "federal authority" are almost identical.

Finally, visit the National Constitution Center website. They have a "Drafting Table" tool that shows how the language of the 14th Amendment changed before it was finalized. Seeing the "rejected" versions of the law helps you understand why cartoonists chose specific images to represent the final version.