Plutonium is the heavyweight champion of the periodic table, but not in a way that makes you want to invite it over for dinner. It’s sitting right there at atomic number 94. It’s dense. It’s silvery. It’s also arguably the most controversial substance humans have ever pulled out of a reactor. When you find plutonium in periodic table charts, it’s tucked away in the actinide series, that "island" of elements at the bottom that most people ignore in high school chemistry. But ignoring it is a mistake.

It glows. Sorta. Not the cartoonish neon green you see in The Simpsons, but it generates enough internal heat from radioactive decay that a large piece of it feels warm to the touch, like a living creature. If you have enough of it in one place, it can literally boil water. Honestly, it’s a bit unsettling.

The Identity Crisis of Element 94

Plutonium didn't just appear. It was "born" in 1940 at the University of California, Berkeley. Glenn T. Seaborg and his team hit uranium with deuterons. They were looking for something new, and they found a beast.

The thing about plutonium in periodic table classifications is that it belongs to the transuranium elements. These are the elements with atomic numbers greater than 92 (uranium). Almost all of them are synthetic. You won’t find a plutonium mine in the Rockies. It exists in nature only in vanishingly small traces within uranium ores, where it’s created by natural neutron capture. Basically, if you want plutonium, you have to make it.

The chemistry is a nightmare. Most elements behave themselves. Carbon likes four bonds. Oxygen likes two. Plutonium? It has six different allotropes (solid forms) at standard pressure, and it changes between them with the slightest nudge in temperature. It expands and contracts wildly. When it oxidizes, it can increase in volume by up to 70%, which is a terrifying trait if you're trying to store it in a sealed container. It’s like trying to keep a shape-shifting ghost in a box.

🔗 Read more: Turning off group messaging iPhone: Why it is actually harder than it looks

Why We Actually Care About It

Most people hear "plutonium" and think "bomb." They aren't wrong. The Fat Man bomb dropped on Nagasaki used a plutonium-239 core. It’s the go-to material for nuclear weapons because it has a lower critical mass than uranium. You need less of it to make a big bang.

But there’s a flip side that’s actually pretty cool.

- Space exploration would be dead in the water without it.

- We use Plutonium-238 (a different isotope) as a heat source.

- It powers Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs).

Think about the Voyager probes. They’ve been flying for nearly 50 years. They are billions of miles away where the sun is just a bright star. Solar panels are useless out there. Those probes are still talking to us because of the steady, decaying heat of a few kilograms of plutonium. It’s the ultimate long-life battery. The Mars Curiosity and Perseverance rovers use it too. Without plutonium in periodic table applications like these, we’d know basically nothing about the outer solar system.

The Isotope Shuffle

Not all plutonium is created equal. This is where people get confused.

Plutonium-239 is the fissile stuff. You get it by "breeding" uranium-238 in a nuclear reactor. It’s the backbone of the global nuclear arsenal.

Plutonium-240 is the "contaminant." It’s highly radioactive and undergoes spontaneous fission. If you have too much 240 in your 239, the bomb might "fizzle"—it explodes prematurely and with much less force. This is why "weapons-grade" plutonium is a specific, highly refined thing.

Then there’s Plutonium-238. You can’t make a bomb with it. It just gets really, really hot. This is the "space battery" isotope. It’s expensive to make, and we actually ran low on it for a while, causing a minor panic at NASA about a decade ago.

The Toxic Reputation

Is it the "most toxic substance known to man"?

👉 See also: Why Every Picture of a Robot Looks Different (and Why it Matters)

Probably not.

Botulinum toxin is technically more lethal by weight. But plutonium is uniquely scary because of how it hurts you. It’s an alpha emitter. Alpha particles are heavy and slow; they can be stopped by a sheet of paper or your skin. You could probably hold a puck of plutonium in your hand and be fine (though I wouldn't recommend it).

The danger starts if you breathe it in.

If a microscopic speck of plutonium dust gets lodged in your lung tissue, those alpha particles hit the same few cells over and over again. It’s like a tiny machine gun firing at your DNA. That’s how you get cancer. It also mimics calcium in the body. If it gets into your bloodstream, your bones "think" it's calcium and pull it into the marrow. Once it’s in your bones, it stays there for decades, irradiating you from the inside out.

Managing the Legacy

Since the end of the Cold War, we’ve had a massive problem: what do we do with all the leftover plutonium? We have hundreds of tons of the stuff sitting in vaults.

📖 Related: EU Data Privacy News Today: Why Your "Anonymous" Data Just Got a New Label

Some of it is being turned into MOX fuel—Mixed Oxide fuel. You mix plutonium oxide with uranium oxide and burn it in a commercial nuclear power plant. It’s a "swords into plowshares" situation. But it’s expensive and politically messy. Some countries, like France, are big on it. The U.S. has struggled to get its MOX programs off the ground due to massive cost overruns at sites like Savannah River.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you’re looking to understand the role of plutonium in periodic table dynamics more deeply, don't just look at the chemical symbol (Pu). Look at the geopolitics.

- Check out the IAEA reports: The International Atomic Energy Agency tracks "significant quantities" of plutonium. It’s the best way to see who has what.

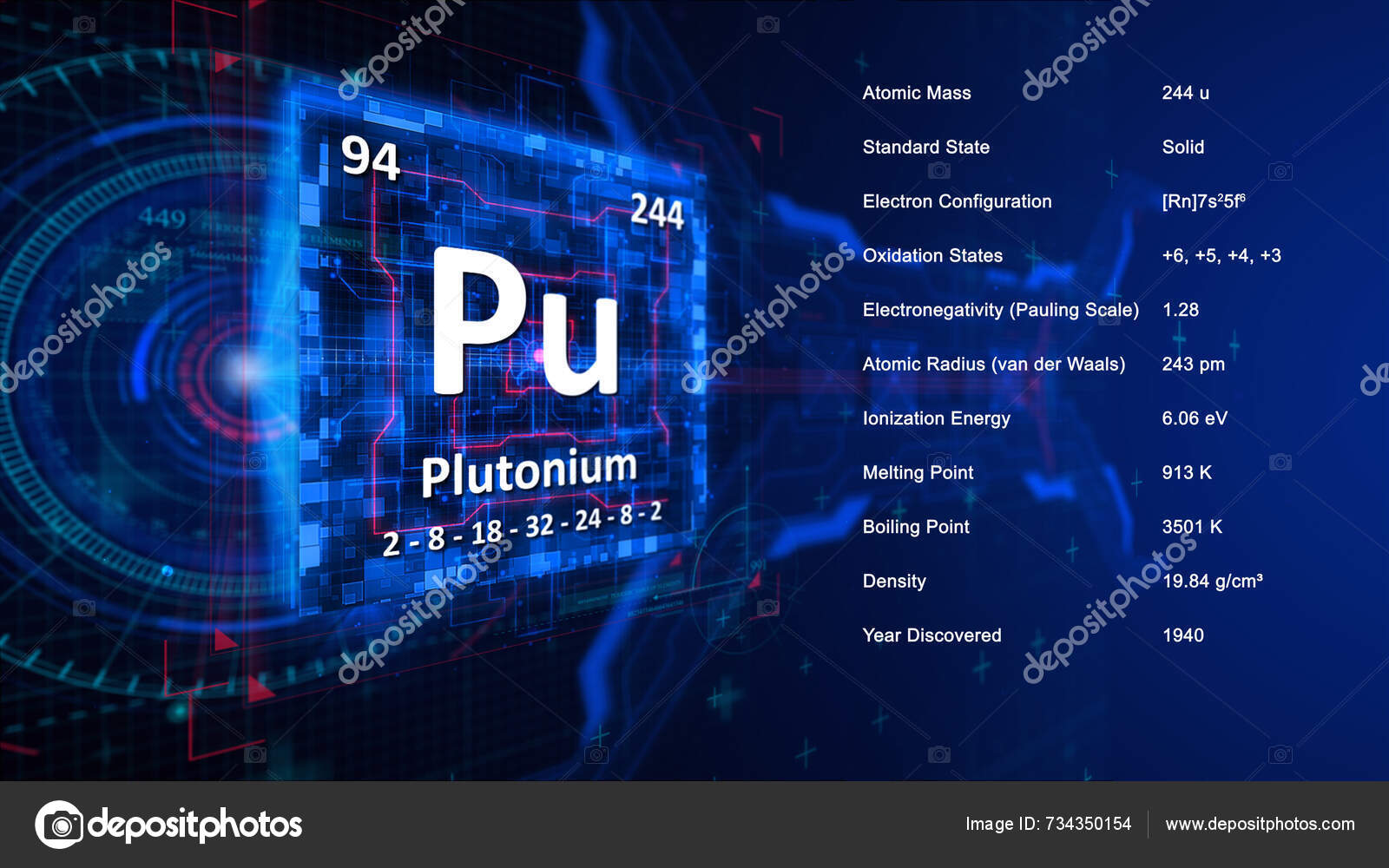

- Study the actinide contraction: If you’re a chemistry nerd, look up why the atomic radius of elements in this row shrinks as you add protons. It explains why plutonium’s density is so weird ($19.84 g/cm^3$).

- Monitor NASA’s RPS program: The Radioisotope Power Systems program is always looking for new ways to use Pu-238 for deep-space missions.

- Look at the WIPP site: The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico is where the U.S. stores its transuranic waste. Their "long-term warning" signs are a fascinating study in semiotics—how do you tell someone 10,000 years from now that a place is dangerous?

Plutonium isn't just a square on a chart. It’s a mirror. It shows our highest aspirations in the stars and our darkest capabilities here on Earth. It’s a volatile, complicated, and strangely warm metal that we’re stuck with for the next 24,000 years (its half-life). We might as well understand it.

To truly grasp the scale of this element, research the "demon core" incidents at Los Alamos. It provides a sobering look at how a few centimeters of material can change the course of lives in a fraction of a second when criticality is reached.