Ever tried sketching the plot of log x by hand and ended up with a line that looks like it just gave up? It happens. Most people treat logarithms like some mystical math beast that only exists to ruin their GPA, but honestly, the graph is one of the most elegant things in mathematics once you stop overthinking it. It’s the visual representation of how things grow when they’re constantly being "scaled down" by a factor of ten. Or $e$, if you’re into natural logs.

The Shape That Never Quite Hits Zero

The first thing you’ll notice when you look at a plot of log x is that it’s incredibly picky about its neighborhood. It refuses to hang out on the left side of the y-axis. Why? Because you can’t take the log of a negative number in the real number system. Even trying to find $\log(0)$ is a recipe for a "Math Error" on your calculator. The graph approaches the y-axis like a shy kid at a party—getting closer and closer but never actually touching it. This is what we call a vertical asymptote.

Think about it. $10^y = x$. If $x$ is zero, what could $y$ possibly be? There’s no power you can raise 10 to that results in zero. It’s impossible. So, the curve dives down into a bottomless pit as $x$ gets closer to 0. It’s dramatic. It’s infinite. It’s literally the definition of "getting close but no cigar."

The Magic Point: (1, 0)

Every standard plot of log x (assuming no fancy shifts or stretches) passes through the point $(1, 0)$. This is the universal truth of logs. Whether it’s $\log_{10}$ or $\ln$, the log of 1 is always 0. It’s the anchor. If your graph doesn't hit that point, you’ve probably shifted the function left or right.

But then something weird happens. The graph starts to grow, but it’s lazy. It’s the opposite of an exponential curve. While an exponential graph like $y = 10^x$ explodes toward the ceiling, the log graph starts to flatten out. It’s still going up—it never stops going up—but it takes its sweet time. To get the y-value from 1 to 2, you need $x$ to jump from 10 to 100. To get to 3? You need $x$ to hit 1000. That’s a massive amount of horizontal "work" for a tiny vertical "gain."

📖 Related: Why the Official Cable Lightning 2m Apple Still Wins Despite the USB-C Switch

Why the Base Matters (But Also Doesn't)

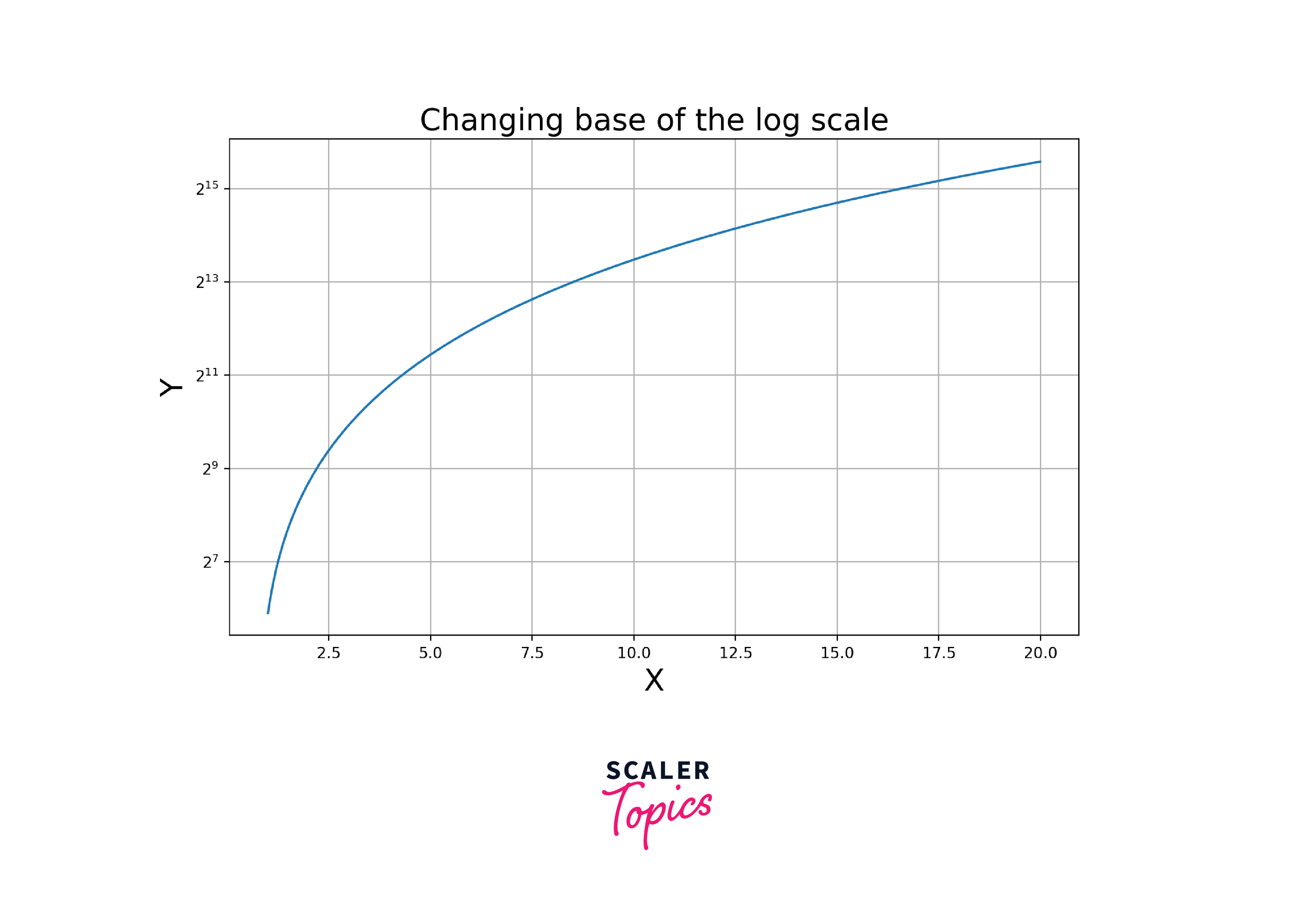

Most students get hung up on whether they are plotting $\log_{10}(x)$ or $\ln(x)$. Here is the secret: they look almost identical. Seriously. If you didn’t have the axes labeled with specific numbers, you couldn’t tell them apart at a glance. They both have that same "swoosh" shape. They both cross through $(1, 0)$. They both have that vertical asymptote at $x = 0$.

The only difference is the "steepness." A natural log ($\ln$) grows slightly faster because its base is $e$ (about 2.718), which is smaller than 10. A smaller base means the "scaling down" effect is less aggressive. Imagine two hikers. One is hiking a $\log_{10}$ hill and the other a $\log_2$ hill. The $\log_2$ hiker is going to feel like they are climbing a much steeper cliff because the numbers don't need to get nearly as big to push the output higher.

Common Mistakes When Sketching

- Drawing it like a square root: People often confuse the two. A square root graph $y = \sqrt{x}$ actually starts at $(0, 0)$. The plot of log x never touches the origin.

- The Flatliner: Some people draw the tail end so flat it looks like a horizontal line. It’s not. It will eventually reach a billion, a trillion, and infinity. It just needs a lot of room on the x-axis to get there.

- Crossing the line: Don’t let your pen slip into the negative x-zone. That’s a "straight to jail" offense in the world of calculus.

Real World Vibes: Where This Graph Actually Lives

We don't just draw the plot of log x to pass midterms. It’s everywhere. Ever heard of the Richter scale for earthquakes? That’s a logarithmic scale. When you see a "magnitude 7" versus a "magnitude 8," the graph tells you the latter is actually ten times more powerful. Our ears even hear sound logarithmically. That’s why decibels are a thing. If sound was linear, a rock concert would literally explode your eardrums compared to a whisper. The logarithmic nature of our hearing "compresses" the range so we can process both a pin drop and a jet engine.

In finance, we use log scales to look at stock prices over decades. If a stock goes from $1 to $2, that’s a 100% gain. If it goes from $100 to $101, that’s a 1% gain. A standard linear plot makes that $1 jump look the same in both cases. But a plot of log x (or a semi-log plot) shows you the percentage change. It’s the only way to see the "truth" of long-term growth.

🔗 Read more: How to Fix the Right Click in Laptop Problem (Even If Your Trackpad Is Broken)

Working With Transformations

If you see $y = \log(x - 3)$, the whole graph just slides three units to the right. The "forbidden zone" now starts at $x = 3$. If you see $y = \log(x) + 5$, the whole thing jumps up. It’s like moving a piece of furniture around a room; the shape of the chair doesn't change, just where you put it.

The hardest one for people is usually the negative sign: $y = -\log(x)$. This flips the whole thing upside down. Instead of a bottomless pit at $x = 0$ and a slow rise, you get a towering skyscraper at $x = 0$ that crashes down and slowly sinks forever. It’s the "reflection" over the x-axis.

Technical Nuance: The Derivative

If you’re in a calculus class, you know the slope of this graph is $\frac{1}{x}$. This explains everything about the shape. When $x$ is small (like 0.1), the slope is huge (10). That’s why the graph is so steep near the y-axis. When $x$ is huge (like 1,000), the slope is tiny (0.001). That’s why it looks like it’s flattening out. The math and the picture match up perfectly. It’s rare when things in life are that consistent.

👉 See also: Why Your SO4 2- Lewis Structure Is Probably Wrong (and How to Fix It)

Actionable Steps for Perfect Graphs

- Identify the asymptote first. Draw a dashed vertical line where the "inside" of the log equals zero. This is your "no-go" zone.

- Mark the x-intercept. Unless there is a horizontal shift, it’s always $(1, 0)$.

- Pick one easy power. If it's base 10, plot $(10, 1)$. If it's base 2, plot $(2, 1)$. This gives you the scale.

- The Swoosh. Connect these with a smooth curve that dives down along the asymptote and gently curves away into the distance.

- Check for reflections. If there’s a negative sign in front, flip it. If there’s a negative sign on the $x$, flip it over the y-axis (though that's rare in basic problems).

The plot of log x isn't trying to trick you. It’s just a way of showing how the world looks when you care more about orders of magnitude than simple addition. Once you get the "swoosh" right, everything else in algebra starts to click. Use a graphing tool like Desmos if you really want to see the nuance of how changing the base affects the curve in real-time. It's oddly satisfying to watch.