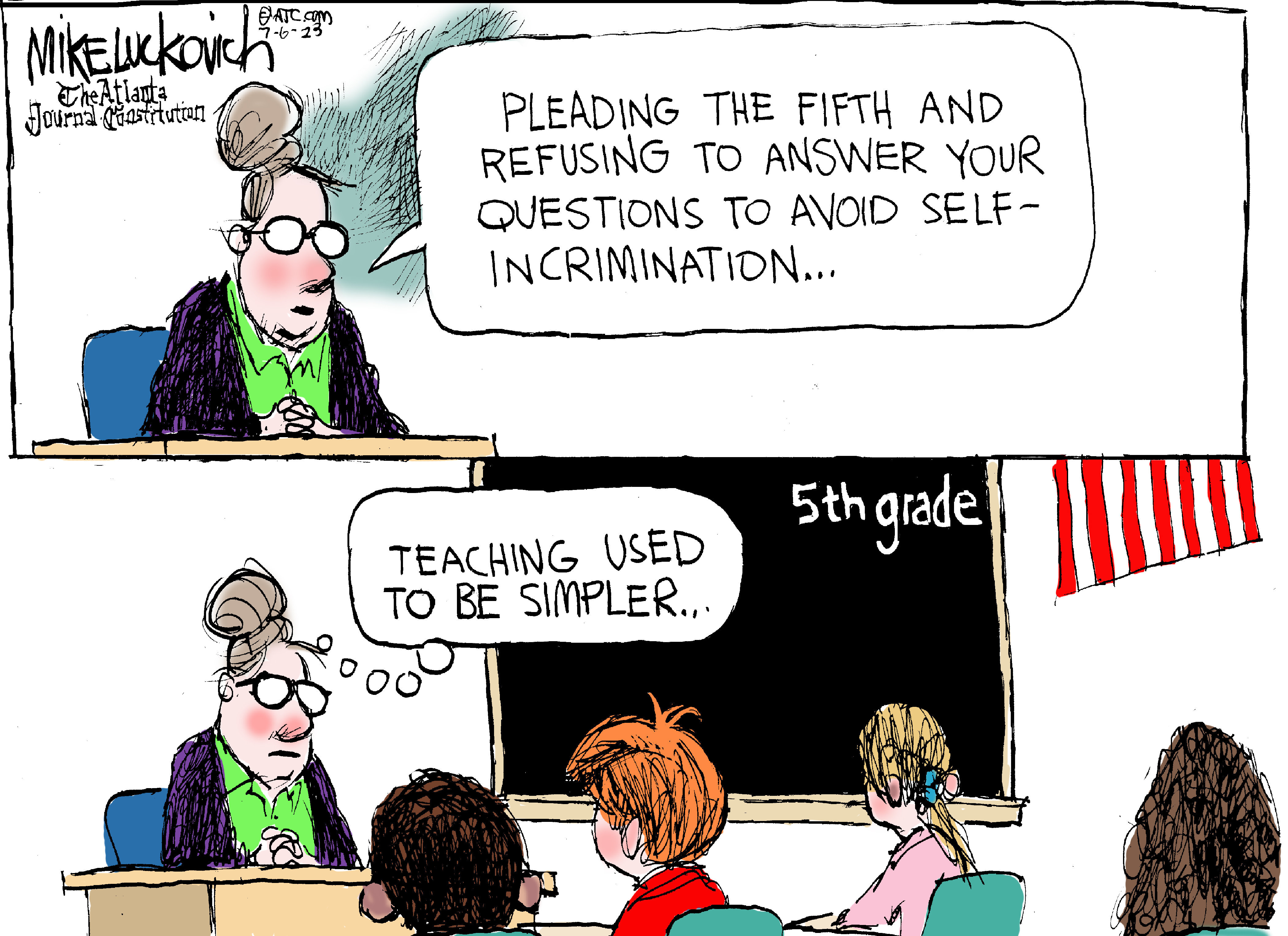

You’ve seen it a thousand times in movies. A witness sits behind a microphone, sweating under fluorescent lights, and mutters, "I refuse to answer on the grounds that it may incriminate me." We usually assume they're hiding something juicy. Honestly, most of us think the definition of plead the fifth is basically just "legal-speak for I did it."

But the law doesn't see it that way.

The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is one of the most misunderstood pieces of paper in history. It isn't a "get out of jail free" card, and it definitely isn't an admission of a crime. It’s a shield. It exists because the Founding Fathers were genuinely terrified of the government using "star chamber" tactics—basically, torturing or bullying people until they confessed to things they didn't even do.

What is the Actual Definition of Plead the Fifth?

At its most basic level, the definition of plead the fifth refers to the act of invoking your right against self-incrimination. This right is found in the Fifth Amendment, which states that no person "shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself."

It sounds simple. It isn't.

First off, you can't just "plead the fifth" because you're embarrassed. You also can't do it because you want to protect your best friend or your shady uncle. The privilege is personal. It only applies if the testimony you are about to give could reasonably lead to you being prosecuted for a crime. If a prosecutor asks you what color your car is, and your car isn't stolen, you can't plead the fifth just to be difficult.

The "Innocent Man's" Problem

Why would an innocent person ever stay silent? Justice Robert Jackson—a former U.S. Supreme Court Justice and a guy who literally led the Nuremberg trials—explained it best. He noted that even the most innocent person can get tripped up by a clever prosecutor. You might get a date wrong. You might misremember a detail. Suddenly, you aren't just a witness; you’re a defendant facing perjury charges.

🔗 Read more: The Brutal Reality of the Russian Mail Order Bride Locked in Basement Headlines

The Supreme Court reinforced this in Ohio v. Reiner (2001). They explicitly stated that the privilege serves the innocent as well as the guilty. It’s a protection for the "innocent who otherwise might be ensnared by ambiguous circumstances."

How It Actually Works in Court (and Why TV Gets It Wrong)

On Law & Order, someone pleads the fifth and the jury looks at them like they're the devil. In a real criminal trial, that’s not allowed.

If a defendant chooses not to testify in their own criminal trial, the judge gives the jury a very specific instruction: you cannot use that silence against them. Period. You can't even talk about it in the jury room. In the eyes of the law, silence is neutral. It's a "no comment" that carries zero legal weight toward a conviction.

However—and this is a big "however"—civil cases are a whole different ball game.

If you’re being sued for money (a civil trial) and you plead the fifth, the judge is allowed to let the jury draw an "adverse inference." Basically, the jury can say, "Well, if they won't answer if they embezzled the money, they probably did." It’s a brutal distinction that catches a lot of people off guard.

The "Waiving" Trap

You can't pick and choose halfway through a story. Legal experts often talk about "waiving" the privilege. If you start answering questions about a specific event, a judge might decide you've opened the door. You can't tell the "good" part of your story and then suddenly go silent when the questions get tough. Once the door is open, you’re usually stuck walking through it.

💡 You might also like: The Battle of the Chesapeake: Why Washington Should Have Lost

This is why defense attorneys often tell their clients to stay completely silent from the jump.

Beyond Just Talking: What the Fifth Doesn't Cover

People think the Fifth Amendment is a blanket of privacy. It’s not.

The definition of plead the fifth only covers "testimonial" evidence. This means things you say or write that communicate a thought. It does not cover physical evidence. The police can legally force you to:

- Give a DNA sample (a cheek swab).

- Provide fingerprints.

- Put on a piece of clothing (like a hat or a glove) to see if it fits.

- Stand in a lineup.

- Give a blood sample (usually with a warrant).

None of that is considered "testifying" against yourself because your body isn't "talking." It’s just existing.

The Modern Frontier: Passcodes and FaceID

Can the police force you to unlock your phone? This is where the law is currently screaming to catch up with 2026 technology.

In many jurisdictions, a passcode is considered "testimonial" because it’s something you know in your mind. Pleading the fifth might work there. But your thumbprint or your face? That’s physical. Some courts have ruled that police can force you to put your thumb on a sensor because it’s no different than taking a fingerprint. It’s a messy, evolving area of law that keeps civil liberties lawyers up at night.

📖 Related: Texas Flash Floods: What Really Happens When a Summer Camp Underwater Becomes the Story

Why We Should Care About the Definition of Plead the Fifth Today

In a world of "cancel culture" and social media trials, silence is often seen as an admission of something terrible. But the legal definition of plead the fifth remains a cornerstone of a fair system. Without it, the burden of proof shifts. Instead of the government having to prove you’re guilty, you would be forced to prove you’re innocent by answering a barrage of questions designed to trap you.

Think about the sheer power dynamic. It’s you versus the entire weight of the Department of Justice or a state's attorney's office. They have the labs, the investigators, and the guns. You have your words. The Fifth Amendment ensures those words can't be turned into a noose around your neck unless you choose to speak.

Real-World Stakes: The Grand Jury

Grand juries are notoriously secretive and one-sided. There’s no judge in the room, and your lawyer usually can't come in with you. In this "shark tank" environment, pleading the fifth is often the only thing keeping a person from being indicted on a whim. Prosecutors often use grand juries to "fish" for information. Without the right to remain silent, a witness could be bullied into providing the very evidence the state needs to lock them up.

Practical Steps If You Ever Find Yourself in a Legal Bind

The law is dense. Even for people who study it, the nuances of the Fifth Amendment are tricky. If you are ever in a situation where you think you need to invoke your rights, keep these things in mind:

- You must say it out loud. You can't just stay silent. The Supreme Court ruled in Salinas v. Texas (2013) that you have to explicitly state you are invoking your Fifth Amendment rights. If you just shut up without saying why, that silence can sometimes be used against you.

- Don't try to be your own lawyer. If the police are questioning you, the best phrase is: "I am invoking my right to remain silent and I want a lawyer." Once you say that, they have to stop.

- Wait for the immunity deal. Sometimes, a prosecutor really wants your testimony to catch a "bigger fish." They might offer you "use immunity." This means nothing you say can be used to prosecute you. Once you have immunity, you cannot plead the fifth anymore because you are no longer in danger of incrimination. If you refuse to talk then, you can be thrown in jail for contempt.

- Civil vs. Criminal. Remember the "adverse inference." If you're in a lawsuit over a car accident or a business deal, pleading the fifth might save you from jail but cost you millions of dollars in the verdict.

- Check the jurisdiction. While the Fifth Amendment is federal, state courts sometimes have their own additional protections (or specific ways they want you to invoke them).

Understanding the definition of plead the fifth isn't about learning how to be a better criminal. It's about understanding the boundaries of power. It's a reminder that in the United States, the government doesn't own your thoughts or your voice. You do.

The right to remain silent is actually the right to be left alone until the state can prove its case with independent evidence. That’s a pretty big deal, regardless of whether you have something to hide or not.

Actionable Insights:

- Memorize the phrase: "I am invoking my Fifth Amendment right to remain silent." Do not rely on "I don't want to talk."

- Understand the scope: Know that this right does not protect you from producing physical documents or biological samples if a valid subpoena or warrant exists.

- Consult an expert: Never attempt to navigate a Grand Jury subpoena or a police interrogation without a qualified criminal defense attorney who can advise when to speak and when to stay quiet.