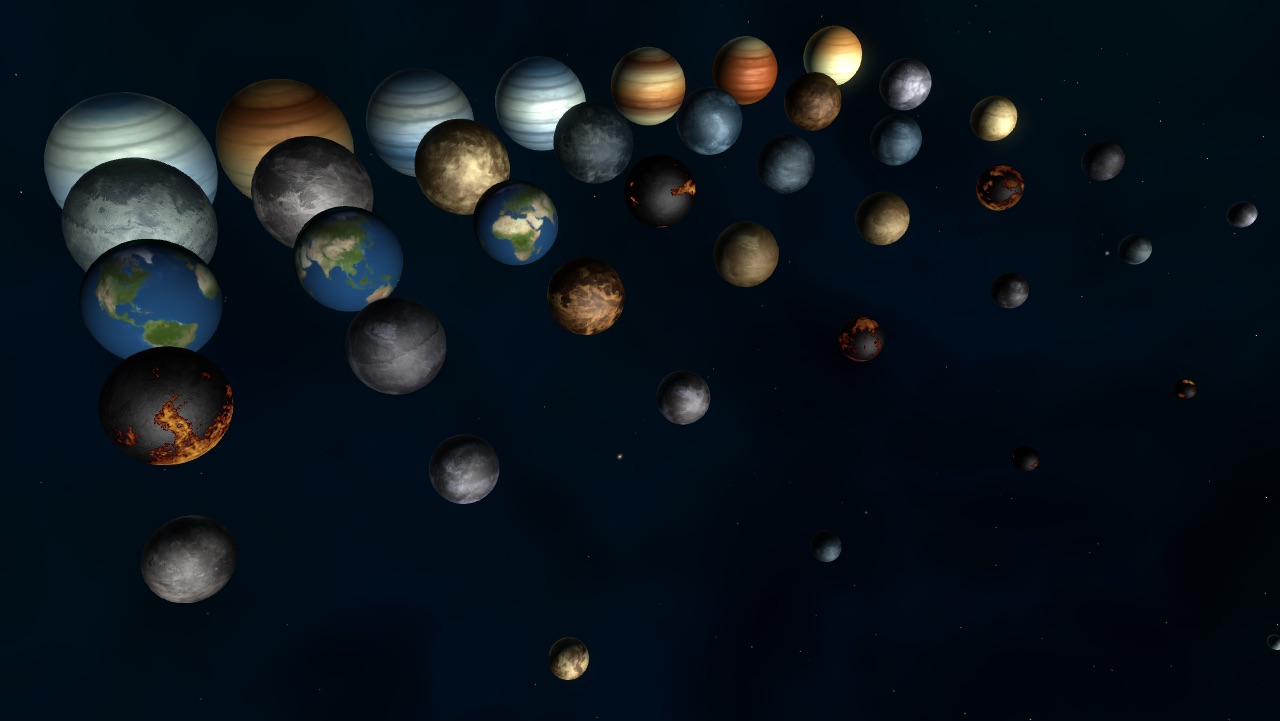

Space is big. Really big. You’ve probably heard that before, but it’s hard to actually wrap your head around how many planets of the universe are out there spinning in the dark. Honestly, it’s kinda terrifying. For a long time, we thought our solar system was the blueprint, a neat little collection of eight planets (sorry, Pluto) orbiting a middle-aged star. Then we started looking closer.

We found out we were wrong.

The universe doesn't care about our "blueprint." Since the launch of the Kepler Space Telescope and now the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), we’ve realized that the variety of worlds out there is basically infinite. We're finding planets made of diamond, planets where it rains glass sideways, and "puffy" planets with the density of cotton candy. It’s not just about finding "Earth 2.0" anymore. It's about realizing how weird physics can get when you give it billions of years and a whole lot of empty space to play with.

Why the Planets of the Universe Don't Look Like Ours

Most people assume that every star system looks like a mirror of our own. Small rocky things near the sun, big gas giants further out. That's the logic, right? Actually, no. One of the first big shocks for astronomers like Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz—who won a Nobel Prize for finding the first exoplanet around a sun-like star—was the discovery of "Hot Jupiters."

Imagine a planet bigger than Jupiter, but it’s sitting closer to its star than Mercury is to our Sun. It’s screaming around its orbit in just a few days. The heat is so intense that the atmosphere literally boils off into space. This threw a massive wrench into our theories of how planets form. We thought gas giants had to form in the cold, outer reaches of a system. 1995 changed everything. It turns out planets migrate. They move. They’re born in one place and pushed into another by gravitational chaos.

The Mystery of the Super-Earths

Here is a weird one: the most common type of planet we find in the galaxy doesn't even exist in our solar system. We call them Super-Earths. They are bigger than Earth but smaller than Neptune.

Why don't we have one? Nobody knows. It’s like a cosmic missing link. Some are rocky, some are "mini-Neptunes" with thick, suffocating gas layers. Dr. Natalie Batalha, a leading researcher in the field, has pointed out that these worlds might be the best place to look for life because they can hold onto thicker atmospheres than Earth. But honestly, they might also be water worlds where the ocean is hundreds of miles deep and the pressure at the bottom turns water into exotic "ice VII," which stays solid even at high temperatures.

🔗 Read more: Why the Gun to Head Stock Image is Becoming a Digital Relic

The Weirdest Worlds We've Actually Found

Let's get specific. When we talk about planets of the universe, we aren't just talking about dots on a graph. We're talking about real, physical places with environments that sound like fever dreams.

Take HD 189733b. At first glance, it’s a beautiful, deep cobalt blue. It looks like a peaceful ocean world. It isn't. That blue color comes from silicate particles in the atmosphere. The wind speeds hit 5,400 mph—seven times the speed of sound. Because of the heat and the silicates, it literally rains molten glass, and it rains it horizontally. You wouldn't just melt there; you’d be shredded.

Then there's 55 Cancri e. This thing is a "diamond planet." It's twice the size of Earth but has eight times the mass. It's so rich in carbon and so pressurized that a significant fraction of its interior is likely pure diamond. It’s worth more than the entire global GDP by a factor of trillions, but the surface temperature is nearly 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Good luck with the mining expedition.

- WASP-12b: A planet being eaten by its star. It’s stretched into an egg shape by gravity.

- Kepler-16b: The real-life Tatooine. It orbits two stars. If you stood there, you’d have two shadows and two sunsets.

- TrES-2b: The darkest planet ever found. It reflects less than 1% of the light that hits it. It’s blacker than coal, glowing with a faint, angry red heat.

The Goldilocks Zone and the Habitability Myth

We talk a lot about the "Habitable Zone." You've heard it: the area around a star where it's not too hot and not too cold for liquid water. But being in the Goldilocks zone doesn't make a planet "Earth-like."

Venus is technically in a habitable-ish area, and it’s a literal hellscape of sulfuric acid and crushing pressure. Mars is in it too, and it’s a frozen desert. When we look at planets of the universe, we have to look at the atmosphere. This is where the JWST comes in. By looking at the light filtering through a planet's atmosphere—a process called transmission spectroscopy—scientists can see the "fingerprints" of molecules like methane, carbon dioxide, and water vapor.

Recently, the detection of K2-18b made waves. It’s a planet in the habitable zone where JWST found carbon-bearing molecules, including methane and CO2. There’s even a faint hint of dimethyl sulfide (DMS). On Earth, DMS is only produced by life—specifically phytoplankton in the ocean. Does that mean we found aliens? Not yet. But it means the search is moving from "Is there a rock there?" to "Is something breathing there?"

💡 You might also like: Who is Blue Origin and Why Should You Care About Bezos's Space Dream?

Rogue Planets: The Orphans of the Cosmos

This is the part that creeps me out. Not all planets orbit stars. There are billions of "rogue planets" drifting through the void of interstellar space. They were kicked out of their home systems by gravitational tug-of-wars during their formation.

They are pitch black. Frozen. Silent.

Scientists estimate there might be more rogue planets in the Milky Way than there are stars. Think about that. For every sun you see in the sky, there might be two or three dark, lonely worlds wandering the empty space between them. Some might even have internal heating from radioactive decay in their cores, potentially keeping subsurface oceans liquid. Life could exist in total darkness, miles beneath a crust of ice, on a planet that hasn't seen a sunrise in five billion years.

The Scale of the Search

We have confirmed over 5,500 exoplanets. That sounds like a lot until you realize there are 100 to 400 billion stars in our galaxy alone. And there are at least two trillion galaxies in the observable universe.

The math is staggering.

$N = R_* \cdot f_p \cdot n_e \cdot f_l \cdot f_i \cdot f_c \cdot L$

📖 Related: The Dogger Bank Wind Farm Is Huge—Here Is What You Actually Need To Know

That’s the Drake Equation. It’s used to estimate the number of active, communicative civilizations in the Milky Way. Even if you’re a pessimist and plug in tiny numbers, the sheer volume of planets of the universe suggests we are almost certainly not alone. The problem isn't the existence of other worlds; it's the distance. Even the closest star, Proxima Centauri, is 4.2 light-years away. With current chemical rockets, it would take us 73,000 years to get there.

Actionable Insights for Amateur Stargazers

You don't need a billion-dollar telescope to appreciate the complexity of the cosmos. If you want to dive deeper into the world of exoplanets and the search for other worlds, here’s how to actually get involved:

1. Follow the NASA Exoplanet Archive

This is the "official" count. It’s updated constantly. They have a "Eyes on Exoplanets" tool that lets you fly through a 3D visualization of discovered systems. It really puts the scale into perspective.

2. Join a Citizen Science Project

You can actually help find planets. Projects like "Planet Hunters TESS" (via Zooniverse) let regular people look at light curves from the TESS satellite. Humans are still better than AI at spotting certain subtle patterns. People have literally discovered planets from their living rooms.

3. Use Augmented Reality Apps

Download apps like SkyGuide or Night Sky. Many now include overlays for where known exoplanets are located. When you look at a random star in the night sky, you can see if we’ve already found a world orbiting it.

4. Keep an Eye on "Biosignatures"

The next five years will be the era of the atmosphere. Watch the news for the term "biosignature" rather than just "Earth-like planet." A biosignature—like the presence of oxygen and methane together—is the "smoking gun" for life.

The universe is much messier, more violent, and more creative than we ever imagined. Our eight planets are just one tiny, relatively quiet corner of a galaxy teeming with worlds we are only beginning to understand. We used to look at the stars and wonder if there were planets. Now we know they’re everywhere. The new question is: who, or what, is looking back?

---