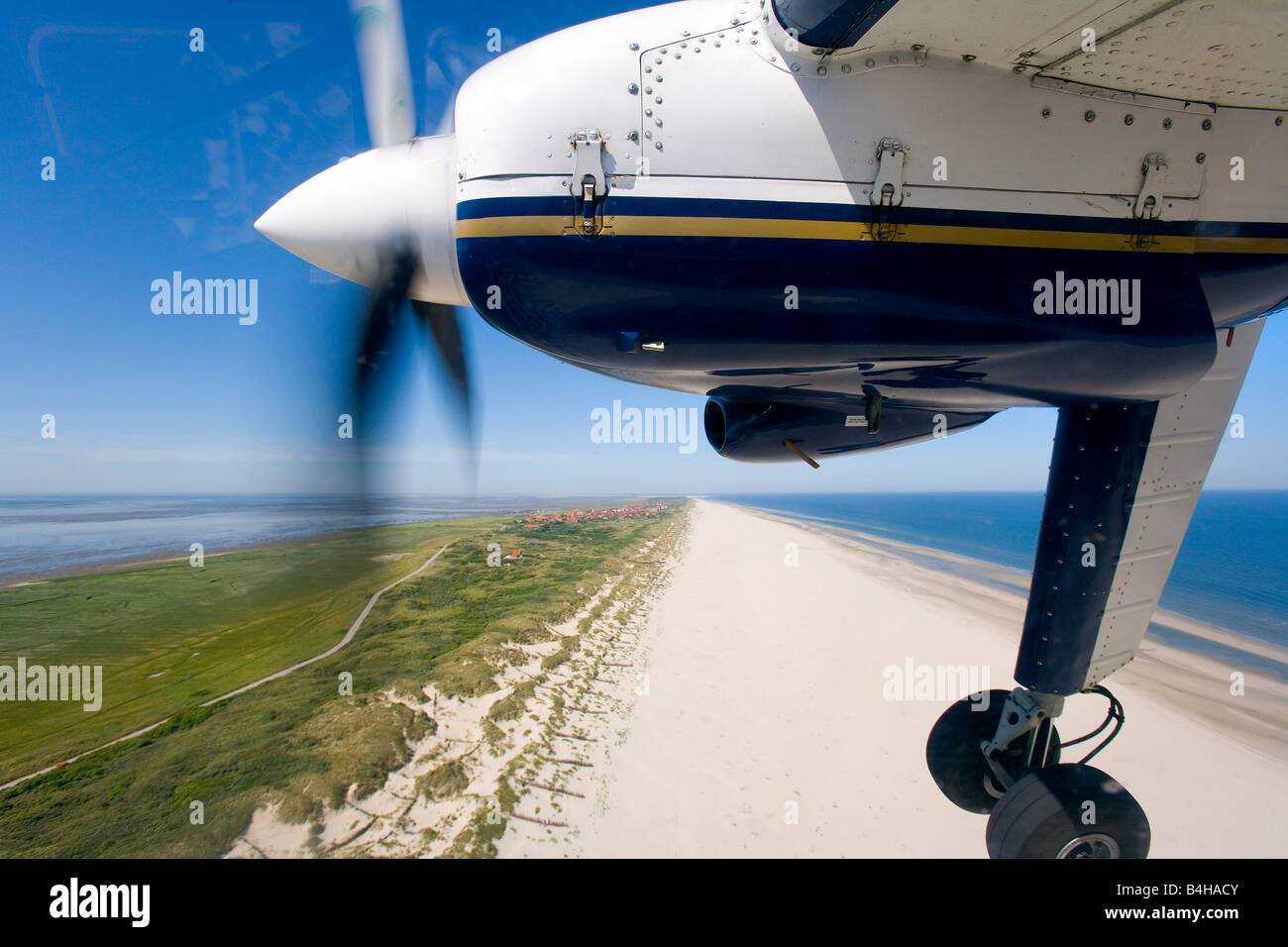

You’re laying there. Sand is everywhere—in your shoes, your hair, probably your sandwich. The sun is hitting just right, and then you hear it. That low-frequency drone that starts as a hum and ends as a rattling roar. You look up and see a plane flying over beach goers, trailing a banner for a local happy hour or maybe just a Cessna 172 sightseeing.

It feels like a classic summer vibe. But honestly, the logistics behind that flight are way more complicated than they look from your towel.

Most people assume these pilots are just out for a joyride. In reality, flying low over a shoreline is one of the most regulated, technically demanding, and—lately—controversial types of aviation. Whether it's advertising, search and rescue, or just "general aviation" (GA) transit, that plane is navigating a legal and physical minefield.

The Law of the Shoreline: How Low Can They Really Go?

When you see a plane flying over beach crowds, your first thought might be: "Is that even legal?"

The FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) is pretty picky about this. Under 14 CFR § 91.119, there are very specific "minimum safe altitudes." Generally, over "congested areas" like a packed South Beach or Santa Monica, pilots have to stay 1,000 feet above the highest obstacle.

But beaches are weird.

If the area isn't considered "congested," the limit drops to 500 feet. And if the pilot is over open water? They just have to stay 500 feet away from any person, vessel, or structure. This is why you’ll see banner planes seemingly "skimming" the water. They are legally allowed to be much lower if they stay a certain horizontal distance from the shoreline.

It’s a loophole. Sorta.

Actually, banner towers (the folks pulling the "Buy One Get One Margarita" signs) have specific waivers. According to the FAA's Volume 5, Chapter 9 of the Flight Standards Information Management System (FSIMS), these pilots get "Certificates of Waiver" that let them operate in ways your average private pilot can't. They’re professionals. They have to be. Dragging a giant mesh sign creates massive drag, changes the plane's center of gravity, and makes an engine failure a nightmare scenario.

🔗 Read more: Finding Alta West Virginia: Why This Greenbrier County Spot Keeps People Coming Back

The Physics of Salt, Sand, and Engines

Flying near the ocean is basically a slow death sentence for an airplane.

Salt air is a chemical monster. Most of these planes—like the ubiquitous Piper Pawnee or the Cessna 150—are made of aluminum. When you mix salt spray with humidity and heat, you get "filiform corrosion." It’s this spider-web-looking decay that eats through the airframe.

I talked to a mechanic at a small strip near Kitty Hawk once. He told me they have to wash the engines of their coastal fleet every single day. If they don't, the salt crusts on the cylinder fins and the engine overheats. Or worse, the salt gets sucked into the intake and starts pitting the internal valves.

Then there’s the wind.

Beaches have "sea breezes." During the day, the land heats up faster than the water. This creates a pressure differential that sucks cool air off the ocean. This air hits the dunes or hotels and creates "mechanical turbulence." A plane flying over beach areas isn't just gliding through smooth air; the pilot is likely fighting constant, invisible bumps caused by the very hotels you’re staying in.

The Privacy Panic: Drones vs. Planes

Lately, the "creep factor" has changed.

Ten years ago, a plane was just a plane. Now, everyone thinks there’s a high-res camera pointed at them. While some police departments use "fixed-wing" aircraft for surveillance—notably in places like Baltimore or during large protests in coastal cities—most small planes you see are too loud and too high to be effective "peeping toms."

The real privacy threat isn't the Cessna. It’s the drone.

💡 You might also like: The Gwen Luxury Hotel Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong About This Art Deco Icon

Drones are silent. They can hover at 100 feet. A plane flying over beach traffic has to keep moving at 60 to 100 knots just to stay in the air. They don't have time to look at your tan lines. However, the optics have shifted. People are more sensitive to being watched, and the sight of a low-flying aircraft now triggers a "surveillance" reflex that didn't exist in the 90s.

Why Banner Towing is Dying (and Why it Matters)

You’ve probably noticed fewer banners lately.

It’s expensive. Between 2022 and 2026, the cost of AvGas (aviation gasoline) has fluctuated wildly, often hovering around $6 to $8 a gallon at coastal FBOs (Fixed Base Operators). When a plane burns 8 to 12 gallons an hour just to pull a sign for a local nightclub, the math stops working.

Digital ads are winning. Why pay a pilot to fly a banner over 10,000 people when you can geofence a Facebook ad to everyone’s phone on that exact same beach for a fraction of the cost?

But here is the catch: humans are "ad-blind" to their phones. We aren't blind to a loud, yellow plane.

Marketing experts like those at Van Wagner Aerial Media argue that aerial advertising has a "recall rate" significantly higher than digital ads. You remember the plane because it’s an event. It’s a physical presence in your space.

Real World Dangers: When Beach Flights Go Wrong

It isn't all sunset photos and cool breezes.

Engine failures over water are a pilot's biggest fear. If the engine quits while a plane flying over beach crowds is at 500 feet, the pilot has maybe 30 seconds to make a decision.

📖 Related: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

- They can't land on the crowd (obviously).

- They can't land in deep water (the plane might flip and sink).

- They have to find "the soft stuff" near the water's edge where people aren't standing.

In 2023, a banner plane crashed into the surf at Huntington Beach, California, during a junior lifeguard competition. It was terrifying. The pilot survived because he ditched in the water rather than hitting the sand. This is the "silent contract" these pilots sign: if things go south, they go into the water to save the people on the shore.

How to Spot What’s Actually Flying Over You

If you want to be "that person" who knows everything on the beach, download a flight tracking app like FlightRadar24 or ADS-B Exchange.

Most GA planes are required to carry an ADS-B Out transponder. If you see a plane flying over beach sand, pull up the app. You can see:

- The N-Number (the plane's "license plate").

- The altitude (watch how it changes as they hit the shoreline).

- The owner (often a local flight school or a small LLC).

If the plane doesn't show up on the app? It might be a military craft or a government-operated flight. Or just a pilot with an old-school plane and a broken transponder (which is a big FAA no-no in busy coastal airspace).

Actionable Takeaways for Your Next Beach Trip

Stop worrying about the "spying" aspect of a standard propeller plane. They are mostly just trying not to hit a bird or a kite. Instead, use these insights to actually enjoy the view or stay safe:

- Watch the Kites: If you are flying a heavy-duty kite or a drone, keep it under 400 feet. Pilots flying over beaches are often lower than they should be, and a kite string can slice through a wing flap like a cheese wire.

- Identify the "Go-Around": If you see a plane circling the same spot three times, they aren't looking at you. They are likely waiting for a "landing slot" at a nearby coastal airport or checking the water for a search and rescue mission.

- Check the Tail: If the tail looks like it has a "hook" or a "bumper" on it, that's a banner plane. Even if it isn't pulling a sign right now, it's headed to a nearby grass strip to "pick up" a banner.

- Listen for the Engine: A "surging" sound usually means the pilot is adjusting the mixture for the humid sea-level air. It’s a sign of a pro, not an engine failure.

The next time you see a plane flying over beach umbrellas, remember the pilot is likely working harder than you are. They are navigating salt, wind, strict FAA rules, and the constant threat of a bird strike—all so you can have a slightly more interesting view of the horizon.

Keep your eyes on the horizon. The math of aviation is always more interesting than the tan lines.