If you grew up watching Julie Andrews twirl with a parasol or Emily Blunt slide up a banister, you don't actually know Mary Poppins. Honestly. The cinematic version is a sugary confection, a "practically perfect" nanny who uses magic to fix broken families. But when you crack open the original P.L. Travers Mary Poppins books, you find someone else entirely. She’s vain. She’s prickly. She’s occasionally downright terrifying.

Travers didn't write for children. Not really. She wrote for herself, weaving together Eastern mysticism, Celtic folklore, and a very personal, very sharp-edged view of what it means to be a child in a world governed by adults.

The Woman Behind the Umbrella

Pamela Lyndon Travers was a piece of work. Born Helen Lyndon Goff in Queensland, Australia, she reinvented herself in London as a poet, actress, and journalist. She was obsessed with myths. She studied under the mystic G.I. Gurdjieff. She was a friend to W.B. Yeats.

When the first of the P.L. Travers Mary Poppins books arrived in 1934, it wasn't a cozy bedtime story. It was a sensation because it was strange. Travers' Mary Poppins doesn't love the children. At least, she’d never admit it. She’s more like a Zen master who hits you with a stick to wake you up. She snaps. She huffs. She looks in every mirror she passes because she’s deeply in love with her own reflection.

Wait. That sounds mean, doesn't it?

It’s not. It’s honest. Travers knew that children don't want a "buddy." They want a boundary. They want someone who knows the secrets of the universe but still insists they eat their toast.

Why the P.L. Travers Mary Poppins Books Are Not Bedtime Stories

The structure of these books is episodic. There isn't some grand, sweeping plot about saving Mr. Banks from his soul-crushing job at the bank. In the books, Mr. Banks is just... there. He's a bit of a grump, sure, but the cosmic drama happens in the nursery.

Take the "Bad Tuesday" chapter from the first book. Or the "Christmas Shopping" chapter. In the world of the P.L. Travers Mary Poppins books, the boundaries between the mundane and the mythic are paper-thin. In one moment, Mary is buying fish; in the next, she's conversing with the Pleiades—specifically the star Maia, who has come down to earth to do some shopping for her sisters.

The Darkness You Forgot

Disney would never show you the "Full Moon" chapter. In it, the children go to the zoo at night. But the roles are reversed. The humans are in the cages, and the animals are the observers. The king of this realm is a giant Hamadryad (a king cobra). He calls Mary Poppins his "cousin."

There is a deep, underlying philosophy here about the oneness of all things. Travers was heavily influenced by theosophy. She believed that babies understand the language of the wind and the trees until they grow "too old" and forget. Mary Poppins is the only one who never forgot.

💡 You might also like: Roll Safe: Why the Man Touching Face Meme Still Rules the Internet

- The Vanity: Mary isn't kind. She’s "stern and thin."

- The Magic: It’s never explained. It just is.

- The Departure: She leaves when she wants to. No sentimental goodbyes. She just floats away when the wind changes, leaving the children heartbroken but changed.

The War with Walt Disney

The story of the movie's creation is almost as famous as the book itself, thanks to Saving Mr. Banks. But that movie makes Travers look like a fussy aunt who just needed a hug. In reality, she hated the 1964 film. She wept at the premiere, and they weren't tears of joy.

She hated the animation. She hated the songs. She particularly hated the softening of Mary's character. For Travers, the P.L. Travers Mary Poppins books were about the "Great Exception"—a being who exists between worlds. Turning her into a singing governess felt like a betrayal of the occult roots of the character.

A Reading Order That Makes Sense

If you’re diving in, don't expect a linear narrative. You can basically jump in anywhere, though starting at the beginning helps you ground yourself in the Banks household.

- Mary Poppins (1934) – The one that started it all.

- Mary Poppins Comes Back (1935) – Features the memorable "Bad Day" where Jane gets trapped inside a Royal Doulton bowl.

- Mary Poppins Opens the Door (1943) – My personal favorite, where she arrives via a firework on Guy Fawkes Night.

- Mary Poppins in the Park (1952) – The adventures become more surreal and philosophical.

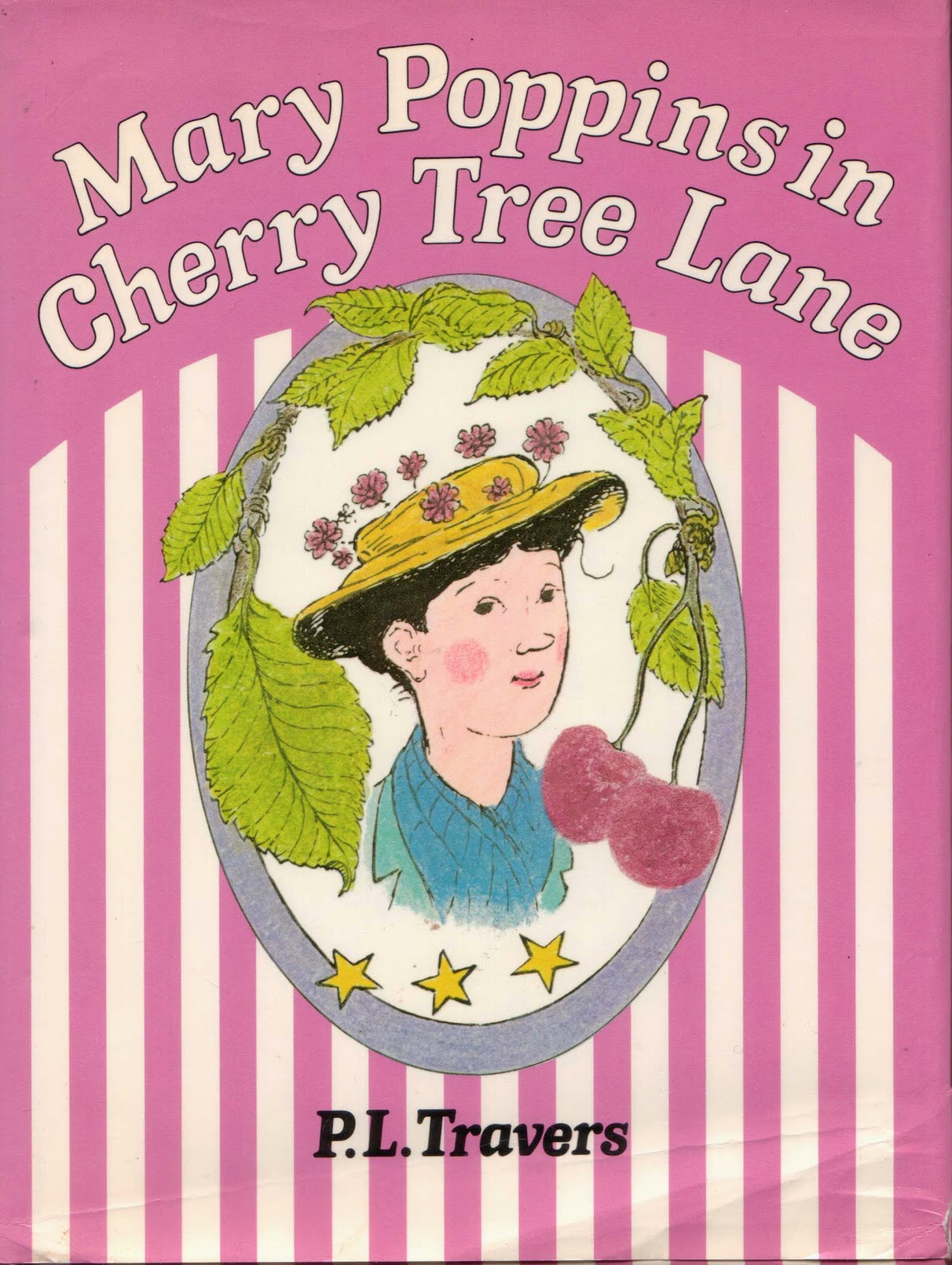

- Mary Poppins in Cherry Tree Lane (1982) – Written much later, focusing on the Midsummer Eve.

- Mary Poppins and the House Next Door (1988) – The final installment, written when Travers was nearly 90.

Most people stop after the first three. That's a mistake. The later books, like Mary Poppins in the Park, contain some of the most profound writing on the nature of reality and shadow. Travers was getting older, and her focus shifted further away from the "nanny" aspect and more toward the "myth."

The Controversy of the Original Text

We have to talk about the "Bad Tuesday" chapter. In the original 1934 version, Mary Poppins uses a compass to take the children to the four corners of the world. The depictions of the people they met—Africans, Chinese, Eskimos, and Native Americans—were based on the most reductive, offensive stereotypes of the 1930s.

Travers didn't change it for a long time. She defended it as "nature" until 1981, when she finally revised the chapter. In the modern version, they meet animals instead of people. It’s a rare instance where the revision actually makes the book better, removing a jarring piece of racism that didn't fit the transcendental themes of the rest of the work.

Why You Should Read Them Now

We live in a world of "sanitized" content. Everything is focus-grouped. Everything has to have a clear moral. The P.L. Travers Mary Poppins books offer something different: a sense of the uncanny.

The books are weirdly comforting precisely because they aren't nice. Mary Poppins is a bit of a bully, but she’s a bully who protects you from the truly terrifying things. She’s the bridge between the nursery and the stars.

If you want to experience the real Mary Poppins, stop watching the movies for a second. Pick up the 1934 original. Read the chapter "The Dancing Cow." It’s a story about a cow who can't stop dancing because a star fell on her horn. It’s beautiful, tragic, and strange.

Actionable Next Steps for Fans

If you're ready to go beyond the movies, here is how to actually engage with the source material:

- Track down the Mary Shepard illustrations. She was the daughter of E.H. Shepard (who drew Winnie the Pooh). Her drawings of Mary Poppins are angular, stiff, and perfect. They capture the "Dutch doll" look Travers intended.

- Read "Mary Poppins in the Park" for the philosophy. If you think these are just kids' books, this volume will change your mind. It deals with concepts of the "Self" that would make a psychology major sweat.

- Listen to the BBC Radio adaptations. They tend to keep the "bite" that the Disney versions filed away.

- Visit the Ashmolean Museum. They hold some of Travers' papers and artifacts. Seeing her handwriting makes the connection to the magic feel a lot more real.

The real Mary Poppins doesn't care if you like her. She doesn't need a spoonful of sugar. She is the wind, the shadow, and the "Great Exception." And she's waiting in the pages of those old books to show you something much more interesting than a cartoon penguin.

To truly understand the legacy of the P.L. Travers Mary Poppins books, you have to accept that magic isn't always kind. Sometimes, magic is a sharp-tongued woman in a blue coat who refuses to explain how she got there.

Pick up a copy of the first book today. Skip the "Introduction" and go straight to Chapter One. Look for the moment she slides up the banister. It's the only thing Disney got exactly right.