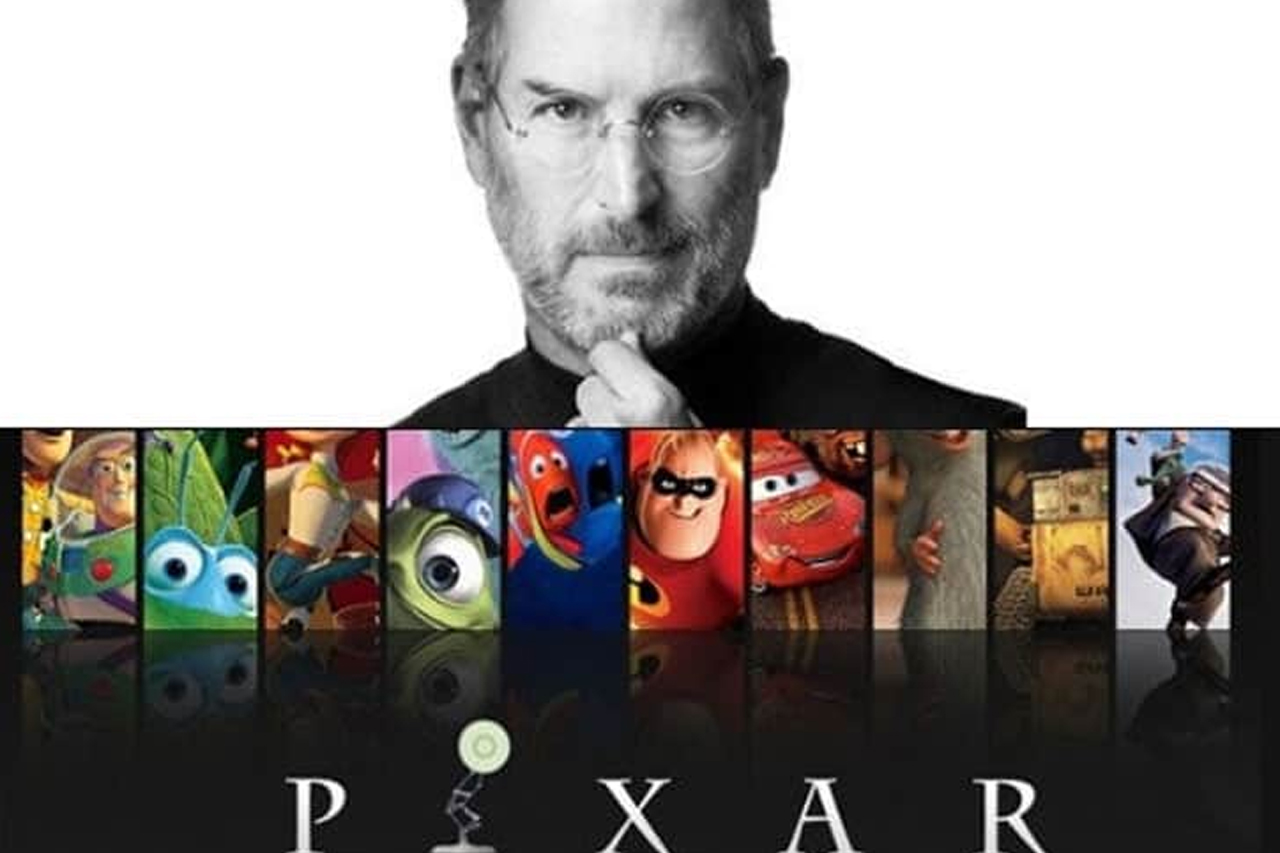

Everyone loves to talk about the iPhone. Or the Mac. But honestly? The most interesting thing he ever did wasn't even at Apple. It was the decade he spent wandering in the wilderness, trying to make a high-end computer hardware company work, and accidentally birthing a movie studio. When people look back at pixar by steve jobs, they usually see a seamless transition from one genius idea to the next.

That’s a lie.

It was messy. It was expensive. It was a money pit that almost broke him. Jobs didn’t buy Pixar because he wanted to make Toy Story. He bought it because he was obsessed with high-end graphics workstations. He thought he was buying a hardware company. He ended up with a bunch of animators and a guy named John Lasseter who just wanted to make a lamp hop around on a desk.

The $5 Million "Mistake"

In 1986, George Lucas was going through a costly divorce and needed cash. He had this "Graphics Group" at Lucasfilm that was doing incredible things, but it was bleeding money. Jobs, freshly ousted from Apple and fueling his new venture, NeXT, saw an opportunity. He paid $5 million to Lucas and put another $5 million into the company’s treasury.

He renamed it Pixar.

At the time, the core product wasn't a movie. It was the Pixar Image Computer. It cost $135,000. It was meant for scientists and doctors. Guess how many they sold? Not many. It was a total flop. Jobs was losing millions of dollars every year, pouring his own personal fortune—the money he made from the Apple IPO—into a company that had no clear path to profitability.

Most people would have quit.

🔗 Read more: Price of Tesla Stock Today: Why Everyone is Watching January 28

Jobs stayed. Why? Maybe it was ego. Maybe it was a genuine belief that the intersection of "art and technology" was where the future lived. He kept the animation department alive almost as a hobby, or a way to show off what the hardware could do. While the hardware sales cratered, the tiny team of animators was winning Oscars for short films like Tin Toy.

How the Disney Deal Changed Everything

By the early 90s, the hardware dream was dead. The software dream (RenderMan) was okay, but not "change the world" okay. Pixar by Steve Jobs was essentially a failing startup that had survived on his stubbornness for five years.

Then came the Disney deal.

Jeffrey Katzenberg at Disney saw the potential in these computer-animated shorts. They signed a three-picture deal. The first was Toy Story. But here is where the "Business Steve" really showed up. He knew that if Toy Story was a hit, Disney would own everything. He needed leverage.

So, he did something incredibly ballsy.

He decided to take Pixar public one week after Toy Story premiered in 1995. It was a massive risk. If the movie bombed, the IPO would fail, and he’d be out of money. If the movie was a hit? He’d have the cash to stand toe-to-toe with Disney.

💡 You might also like: GA 30084 from Georgia Ports Authority: The Truth Behind the Zip Code

The movie was a phenomenon. The IPO was the biggest of the year. Suddenly, the guy who got kicked out of his own company was a billionaire. Not because of Apple, but because of a toy cowboy and a space ranger.

The Culture of "The Braintrust"

One thing people get wrong is thinking Jobs ran Pixar like he ran Apple. He didn't. At Apple, he was a micromanager. At Pixar, he realized he didn't know anything about storytelling.

He stayed out of the story room.

Instead, he focused on the environment. He designed the Pixar headquarters in Emeryville with a central atrium. Why? Because he wanted the computer scientists to bump into the animators. He wanted people to have "unplanned encounters." He believed that creativity happened in the hallway, not the boardroom.

This led to the "Braintrust"—a group of directors who would give brutally honest feedback to each other. It was a culture of "radical candor" before that was a buzzword. Jobs protected this culture. He provided the shield that allowed Ed Catmull and John Lasseter to make mistakes, iterate, and eventually create a string of hits that is statistically impossible in Hollywood.

Why the Disney Merger Was the Final Act

By 2005, the relationship between Pixar and Disney was toxic, mostly because Jobs and Disney CEO Michael Eisner couldn't stand each other. When Bob Iger took over for Eisner, the first thing he did was call Steve.

📖 Related: Jerry Jones 19.2 Billion Net Worth: Why Everyone is Getting the Math Wrong

Iger realized Disney Animation was dying. Pixar was the only thing working.

In 2006, Disney bought Pixar for $7.4 billion. Think about that return on investment. Jobs turned a $10 million investment and a lot of headaches into $7.4 billion and a seat on the Disney board. It made him the largest individual shareholder of Disney.

It also gave him the blueprint for his return to Apple. The lessons he learned about patience, building a brand, and high-stakes negotiation at Pixar were exactly what he used to launch the iPod and the iPhone.

Lessons From the Pixar Years

If you're looking at the history of pixar by steve jobs for business insights, ignore the "visionary" tropes. Look at the grit.

- Keep the lights on for the talent. Jobs funded the animation department even when it made zero financial sense. He recognized talent long before he recognized a business model.

- Pivot when the wall won't move. He wanted to be a hardware king. When the market said no, he didn't die with the hardware; he pivoted to the content.

- Design for serendipity. If you’re building a team, don't just give them tasks. Give them a space where they have to talk to each other. Physical architecture dictates social architecture.

- Wait for your leverage. The 1995 IPO is a masterclass in timing. Don't sell your soul when you're desperate; wait until you have the "hit" to back up your price.

The real story of Pixar isn't about 3D rendering. It's about a man who was humbled by failure, learned to trust people who were smarter than him in their specific fields, and had the deep pockets to wait out a decade of losses. Without those "lost years" at Pixar, the Apple we know today—the trillion-dollar giant—simply wouldn't exist. It was his finishing school. It turned a brash entrepreneur into a corporate statesman.

Next time you watch Toy Story or Finding Nemo, remember that it wasn't just a movie. It was the most expensive, most successful "Plan B" in the history of business.

To apply this to your own projects, start by auditing your "sunk costs." Jobs stopped selling the Pixar Image Computer because it was a loser, even though he loved it. He doubled down on the "shorts" because they were winning awards, even though they didn't make money yet. Follow the excellence, not the original plan. Focus on building a "Braintrust" in your own circle—people who can tell you your idea sucks without making you feel like you suck. That is how you build something that outlasts you.