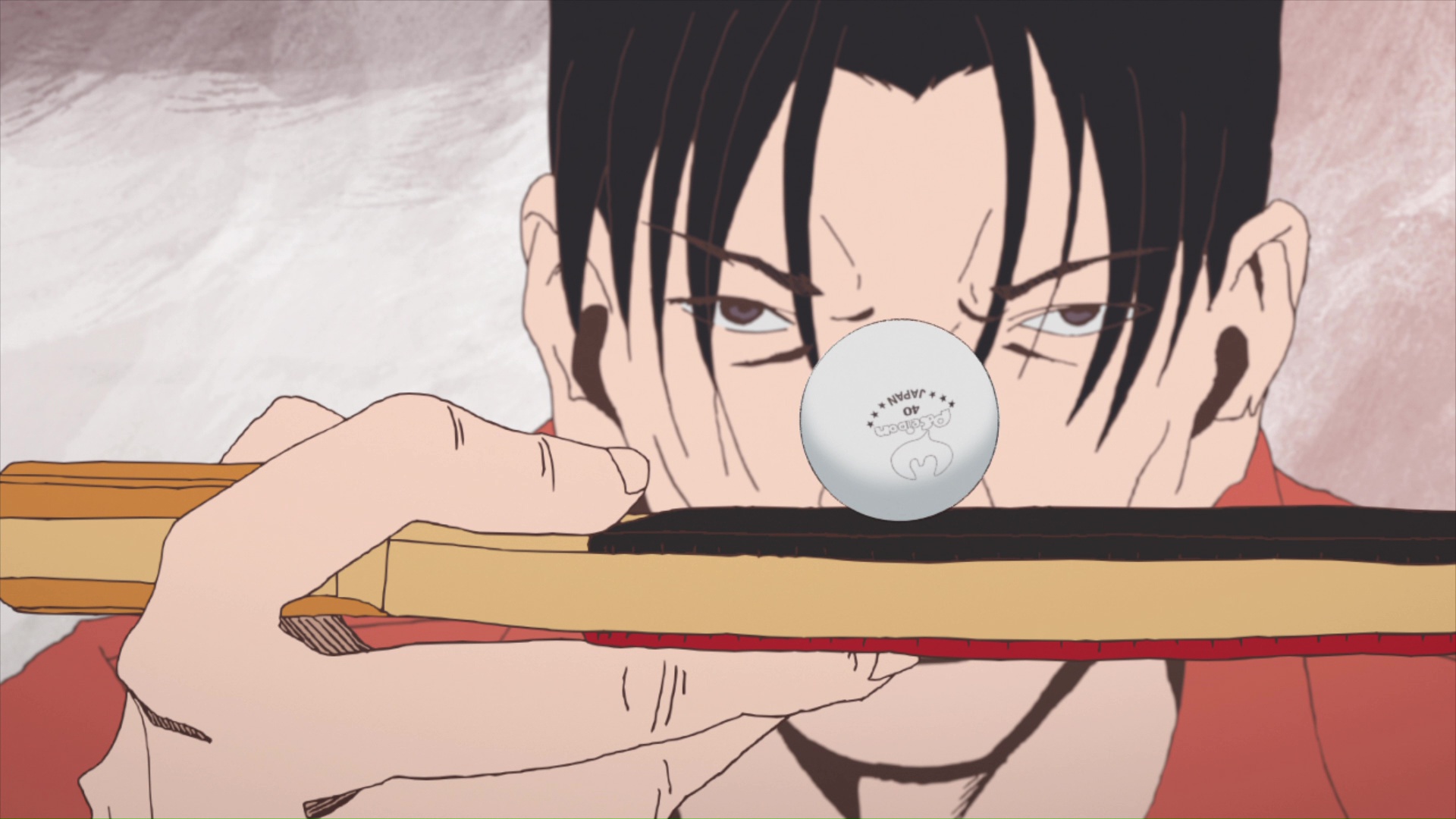

Most people turn off Ping Pong the Animation within the first three minutes. Honestly, it’s hard to blame them. If you’re used to the polished, hyper-saturated aesthetics of Demon Slayer or Jujutsu Kaisen, Masaaki Yuasa’s 2014 adaptation of Taiyo Matsumoto’s manga looks like a collection of crude scribbles. The lines are shaky. The characters have weirdly long limbs. Perspective is treated as a suggestion rather than a rule. But here’s the thing: those people are missing out on what is arguably the most tight, emotionally resonant, and structurally perfect sports anime ever made.

It’s about table tennis. Sorta.

✨ Don't miss: Kenan and Kel Show: What Most People Get Wrong

Actually, it’s about the crushing weight of talent and the even heavier burden of lacking it. It’s about why we try at all when we know someone else is just fundamentally "better" than us. By the time the credits roll on the eleventh episode, you realize the jagged art style wasn't a budget constraint. It was a choice. It’s visceral. It captures the frantic, sweaty, heart-pounding reality of a match better than any "pretty" show ever could.

The Hero and the Robot

The story centers on two childhood friends, Smile (Makoto Tsukimoto) and Peco (Yutaka Hoshino). They are opposites in every way that matters. Peco is loud, arrogant, and lives for the glory of the game. He wants to be the best in the world. Smile, on the other hand, is a defensive specialist who plays with robotic efficiency—hence the nickname—but he lacks "drive." He treats ping pong like a job he didn’t ask for. He’s actually more talented than Peco, but he holds back because he doesn't want to hurt his friend's ego.

This dynamic is the engine of the show. We’ve seen the "talented but lazy" trope before, but Ping Pong the Animation treats it with a level of psychological depth that feels almost uncomfortably real.

Think about it. We’ve all been Peco. You’re the big fish in a small pond, you think you’re a god, and then you hit the real world. You meet a Kong Wenge—an elite player from China who was kicked off his national team and sees playing in Japan as a humiliating exile. When Wenge absolutely demolishes Peco 21-0, the show doesn't just show a loss. It shows a soul breaking. Peco stops playing. He starts eating junk food. He gives up. That’s a human reaction, not a shonen protagonist reaction.

Realism Over Spectacle

Most sports anime rely on "super moves." You know the ones—the ball turns into a dragon, the court disappears into a nebula, someone discovers a secret technique that defies the laws of physics. Ping Pong the Animation rejects all of that.

The "moves" here are real. You see the difference between a shakehand grip and a penhold grip. You see how a chopper plays compared to an attacker. Director Masaaki Yuasa uses split-screen panels (borrowing heavily from the manga's layout) to show the technicality of the sport. You’ll see the ball’s trajectory, the coach’s facial expression, and the opponent’s footwork all at once.

It’s chaotic. It’s fast.

But it’s grounded in the actual mechanics of table tennis. When the animation goes "off-model"—like when a character grows to the size of a mountain or turns into a bird—it’s not a literal power-up. It’s a visual metaphor for how they feel in that moment. When you’re playing someone who is fundamentally better than you, they do feel like a mountain. The show uses its "ugly" art to communicate internal states that "clean" animation simply can't reach.

The Supporting Cast Isn't Just Background Noise

You have to talk about Kong Wenge. He’s one of the best "antagonists" in anime because he isn't a villain. He’s a guy who failed his country’s insanely high standards and is desperately trying to claw his way back. His journey from arrogant outsider to a mentor figure who finds a home in Japan is more moving than the main plot of most other shows.

Then there’s Ryuichi "Dragon" Kazama. He’s the peak of the pyramid. He’s the character everyone fears. But the show lets us inside his head, and it’s a dark place. He’s paralyzed by the fear of losing. He locks himself in a bathroom stall before matches just to breathe. It’s a deconstruction of the "invincible champion" archetype. It asks: is being the best even fun? Or is it just a cage?

Why the Music Matters

Kensuke Ushio’s soundtrack is the secret weapon of Ping Pong the Animation. Before he did the haunting scores for A Silent Voice and Chainsaw Man, he created this pulsing, electronic, industrial masterpiece.

The music often syncs with the sound of the ping pong ball hitting the table. Puck-nick. Puck-nick. It builds a rhythm that becomes hypnotic. In the final matches, the soundtrack takes over, heightening the tension until you’re literally leaning toward your screen. It’s not just background noise; it’s the heartbeat of the series.

Addressing the "Bad Art" Criticism

If you’re still struggling with the visuals, look at the character designs by Nobutake Ito. Yes, they look weird. But they are incredibly expressive. In a traditional anime, characters often have "same-face syndrome" where only their hair changes. In this show, every character has a distinct body type, a distinct way of moving, and a face that actually looks like it has bone structure.

The animation is handled by Science SARU, and it’s remarkably fluid. While the drawings are rough, the motion is top-tier. There is a sense of weight and momentum in the rallies that makes you feel the physical exhaustion of the players. By episode six, you won't even notice the "roughness" anymore. You’ll just see the soul.

The Message You Weren't Expecting

The core of the show is a rejection of the "hard work beats talent" lie. Sometimes, hard work isn't enough. Sometimes, the gap is too wide. And that’s okay.

Ping Pong the Animation argues that your value as a human being isn't tied to your ranking in a tournament. It’s a brave stance for a sports show to take. It suggests that finding joy in the effort, or finding a different path entirely, is just as valid as winning the gold medal.

How to Experience it Best

If you’re going to watch it, don’t binge it in one sitting. Give the episodes room to breathe. The show is only 11 episodes long—it’s a perfect "weekend watch."

- Watch the Sub: While the dub is decent, the original Japanese voice acting (especially for Kong Wenge, who speaks actual Mandarin) adds a layer of authenticity that’s hard to beat.

- Pay Attention to the Backgrounds: The cityscapes and gyms are often painted with a watercolor-like texture that contrasts beautifully with the sharp, jagged character lines.

- Look for the Hero: Keep an eye out for the "Hero" motif. It pays off in one of the most satisfying finales in the history of the medium.

Actionable Takeaways for New Viewers

If you've been on the fence about starting this series, here is how to approach it for the best experience:

- Give it the 3-Episode Rule: The first episode is jarring. The second sets the stakes. By the third, you’ll understand the visual language.

- Focus on the Sound: Use headphones. The foley work (the sounds of the paddles and shoes squeaking) is as important as the dialogue.

- Research Masaaki Yuasa: If you find you like the style, check out The Tatami Galaxy or Devilman Crybaby. He’s a director who prioritizes "feeling" over "perfection."

- Don't Google Spoilers: The tournament bracket has some genuine surprises. The winner of the final match isn't who you’d expect from a standard anime.

This isn't just a show about sports. It’s a show about growing up and realizing that the world is bigger than the table in front of you. It’s messy, it’s loud, and it’s beautiful. Go watch it.

To get the most out of your viewing, try to find the Blu-ray or a high-bitrate stream. The fast motion of the matches can sometimes suffer from compression artifacts on lower-quality sites, which does a disservice to the intricate line work of the animation team. Once you finish, look up the original manga by Taiyo Matsumoto to see how faithfully the "feeling" was translated to the screen.