On a Friday afternoon in November 2010, the ground shook near Greymouth. It wasn't an earthquake. Deep inside the Paparoa Range, a massive methane explosion ripped through the Pike River coal mine. Twenty-nine men were trapped. They never came home.

Most people remember the headlines. They remember the agonizing wait and the grainy footage of the second blast that ended all hope. But if you look closer at the Pike River mine disaster, you realize it wasn't just a "freak accident." It was a systemic collapse. For years, the story has been buried under legal jargon and shifting blame, yet the raw facts are actually way more haunting than the media soundbites suggest.

Honestly, the tragedy started long before the first spark. It started with a company that was broke, desperate, and cutting corners to hit targets that were basically impossible.

The Warning Signs Nobody Wanted to See

Pike River Coal Ltd was under immense pressure. They were behind schedule. They were bleeding cash. When a business is in that kind of hole, safety usually takes a backseat to "meters gained." It’s a classic, tragic pattern.

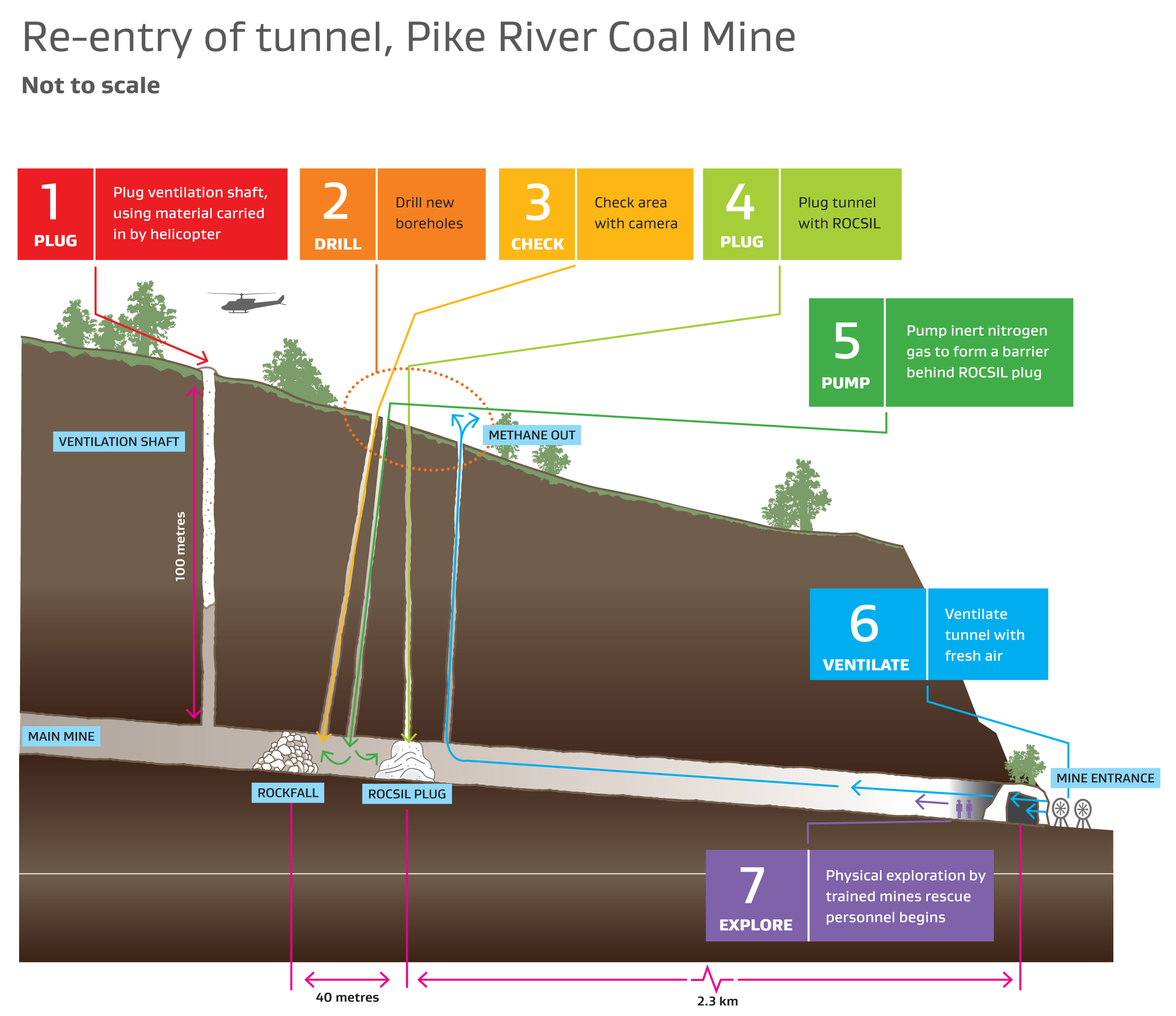

The geology of the Brunner coal seam is notoriously difficult. It’s gassy. Really gassy. To mine there safely, you need world-class ventilation. Pike River didn't have that. They had a single exit point—the main 2.3-kilometer drift—and a ventilation shaft that was also supposed to serve as an emergency escape ladder. Think about that for a second. The "fire escape" was the same hole blowing out all the explosive gas.

And the gas sensors? They were a joke. Records later showed that in the weeks leading up to the Pike River mine disaster, methane levels had spiked to explosive volumes dozens of times. Each time, the alarms would go off, and instead of a total shutdown and rethink, the sensors were often treated like a nuisance. Workers reported that the ventilation fan would fail frequently. Imagine being hundreds of meters underground, knowing the air keeping you alive is glitchy, but feeling the pressure to keep digging because the company's stock price depends on it.

The Royal Commission of Inquiry eventually laid it all out. They found that the Department of Labour—the very people meant to be the watchdogs—basically failed to bark. They didn't have the expertise to inspect a mine this complex. It was a perfect storm of corporate negligence and regulatory weakness.

✨ Don't miss: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

November 19: The Day the Mountain Fired

At 3:44 PM, the methane found an ignition source. We still don't know exactly what the spark was. It could have been an electrical fault; it could have been a localized rockfall. It doesn't really matter. Once that gas ignited, the tunnel became a cannon.

Only two men survived. Daniel Rockhouse and Russell Smith were near the entrance, knocked unconscious but somehow managed to stumble out through the thick smoke. The other 29—ranging from a 17-year-old on his first week to seasoned veterans—were much deeper in.

The next five days were a masterclass in heartbreak. The police took over the operation, treating it like a crime scene rather than a rescue mission, which frustrated the local West Coast mining community. "Coasters" know mines. They wanted to go in. They thought they could save their mates. But the gas levels were off the charts. High levels of carbon monoxide and low oxygen meant that any rescue attempt was basically a suicide mission.

Then, on November 24, a second explosion hit.

That was the "official" end. If anyone had survived the first blast, they certainly didn't survive the second. It was a gut-punch to a nation that had been holding its breath. New Zealand is a small place; twenty-nine men is a huge hole in the fabric of a community like Greymouth.

The Re-entry Battle and the Fight for Justice

For years after the Pike River mine disaster, the families were told it was too dangerous to go back in. The mine was sealed. The government basically said, "Sorry, it's a graveyard now."

🔗 Read more: Passive Resistance Explained: Why It Is Way More Than Just Standing Still

But the families didn't buy it. Led by figures like Anna Osborne and Sonya Rockhouse, they fought for a decade. They protested, they lobbied, and they eventually forced a change in government policy. In 2017, the newly elected Labour-led government stayed true to a campaign promise and formed the Pike River Recovery Agency.

They actually did it. They re-entered the drift.

In 2019, teams finally broke the seal and spent months meticulously exploring the 2.2-kilometer access tunnel. They found evidence—abandoned machines, personal gear—but they didn't reach the "workings" where the men are believed to be. The rockfall at the end of the drift was too unstable. The project ended in 2021, and the mine was sealed again, this time with much more closure for the families, even if the remains of their loved ones weren't recovered.

Why does this matter? Because the re-entry proved that the initial "it’s impossible" narrative was partly about avoiding liability. It showed that with enough political will, you can prioritize people over the "too hard" basket.

Health and Safety: The Legacy of the 29

If there is any "silver lining"—though that feels like the wrong word for 29 deaths—it’s the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015. New Zealand’s safety laws were archaic before Pike River. Now, they’re some of the strictest in the world.

Directors can now be held personally liable for safety failures. You can't just hide behind a shell company anymore. The "she'll be right" attitude that defines a lot of Kiwi culture was officially killed in that mine. It had to be.

💡 You might also like: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

But has justice been served? Not really. No one went to jail. Peter Whittall, the CEO at the time, had charges against him dropped after a controversial deal where money was paid to the families. The Supreme Court later ruled that deal was unlawful, but the damage was done. You can't put the toothpaste back in the tube.

Practical Lessons for the Modern Workplace

We often think of the Pike River mine disaster as a mining-specific tragedy, but the lessons apply to anyone running a business or working in a high-stakes environment.

- Normalize Dissent: If your employees are afraid to tell you that something is broken, your business is a ticking time bomb. The Pike River miners knew the gas was bad. They talked about it in the locker rooms. They just didn't feel they could stop the machine.

- Audit Your Regulators: Don't assume that because you passed a government inspection, you are "safe." The inspectors might not know your specific risks as well as you do.

- Infrastructure Over Opticals: Pike River spent a lot of money on branding and "looking" like a world-class mine while their actual ventilation system was fundamentally flawed. Focus on the bones of the operation.

- The Cost of "Soon": When deadlines drive safety decisions, people die. If you’re a manager and you find yourself saying "we'll fix that after this shipment goes out," stop. That’s exactly what happened at Pike.

Moving Forward

The site of the mine is now part of the Paparoa Track, one of New Zealand’s "Great Walks." It’s beautiful. It’s quiet. It’s a strange juxtaposition to the violence of 2010.

To truly honor the men of Pike River, it’s not enough to just remember their names. You have to look at your own environment—whether it’s a construction site, a kitchen, or a corporate office—and ask: "Is there a 'ventilation fan' in my life that I'm ignoring because it's too expensive to fix?"

The best way to prevent the next Pike River mine disaster is to stop accepting "good enough" when lives are on the line.

Next Steps for Further Understanding:

- Read the Royal Commission Report: It is a dense but vital document that outlines the failure of both the company and the state.

- Visit the Pike River 29 Memorial: If you are ever on the West Coast of the South Island, the memorial at the mine entrance site offers a visceral sense of the scale of the loss.

- Audit Your Safety Culture: Use the "Pike Test"—can the lowest-ranking person in your organization stop a major operation immediately if they see a hazard, without fear of retribution? If the answer is no, you have work to do.