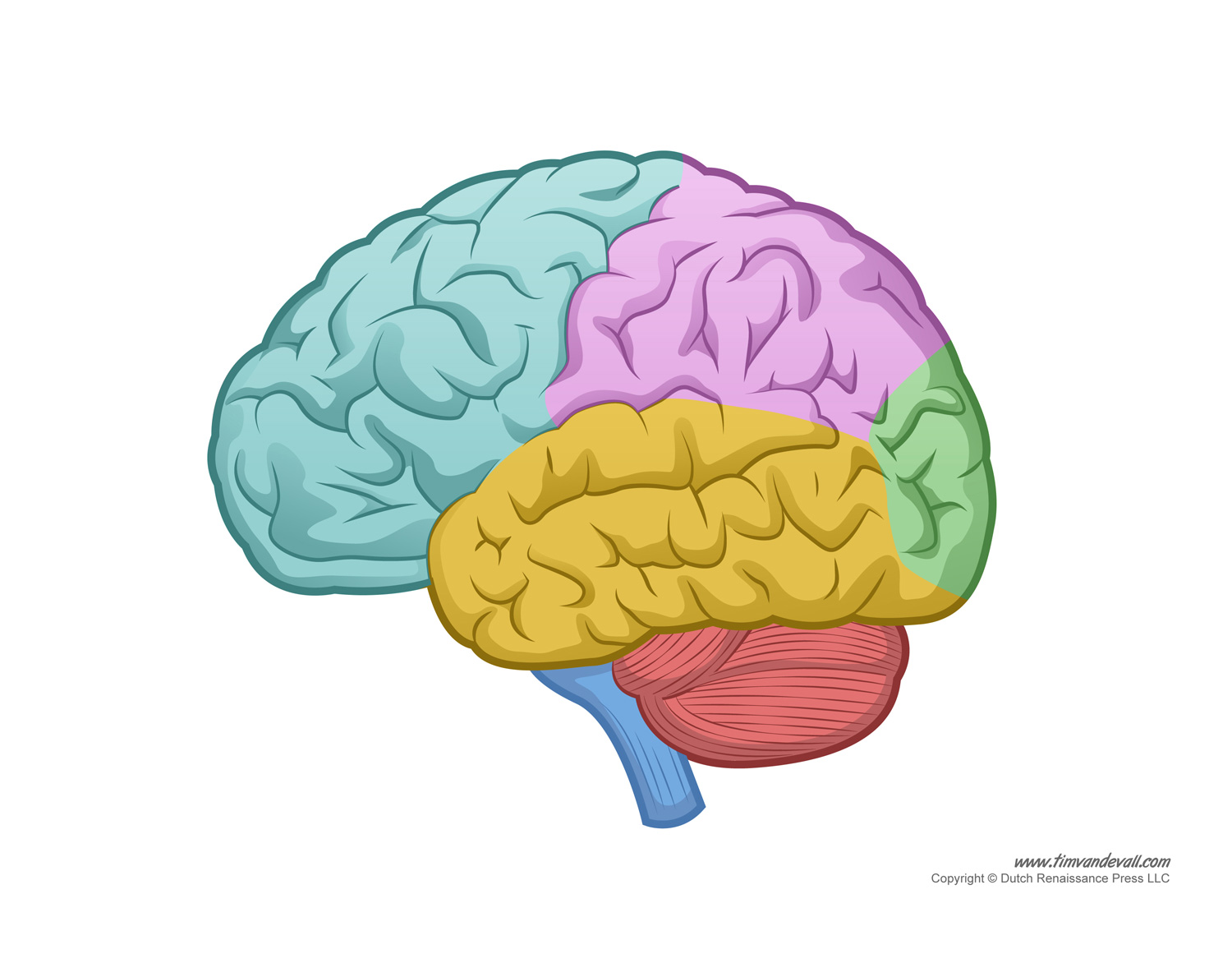

You’ve probably seen those neon-colored diagrams in biology textbooks. You know the ones. The frontal lobe is always a bright, friendly blue, while the occipital lobe sits at the back in a jarring shade of pink. It looks organized. It looks like a map of a very clean city. But if you actually look at pictures of the brain parts from a real MRI or a dissection table, that orderly world vanishes instantly.

The real thing is a 3-pound mass of grayish-pink tissue that looks more like a walnut than a computer chip.

Honestly, it’s messy. When neuroscientists like Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor describe the brain, they aren't talking about static boxes. They’re talking about a fluid, electrochemical storm. Understanding what you're looking at when you scroll through images of the cerebellum or the brainstem requires unlearning that "color-coded" myth. We like to think of the brain as a collection of separate Lego bricks, but it’s actually more like a giant, tangled ball of yarn where pulling one thread vibrates the whole thing.

Why most pictures of the brain parts are misleading

Most of the images we consume are "schematics." They are designed to help you pass a test, not to show you how a human being actually functions. Take the amygdala, for example. In most 3D renders, it looks like a tiny, isolated almond tucked deep inside the temporal lobe. Seeing it that way makes you think, "Okay, that’s where fear lives."

That’s a half-truth at best.

🔗 Read more: Similasan for Pink Eye: What Most People Get Wrong

While the amygdala is central to emotional processing, it doesn't work in a vacuum. It is constantly whispering (or screaming) to the prefrontal cortex. If you look at high-definition fiber tracking—often called diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)—you don’t see an almond. You see a chaotic highway of white matter tracts connecting that "almond" to almost everywhere else. This is why a picture of a single brain part can be so deceptive. It’s like looking at a picture of a steering wheel and trying to understand how an internal combustion engine works. It’s a piece of the puzzle, but the "picture" is the movement, not the part.

The big three: Forebrain, Midbrain, and Hindbrain

When you look at a profile view of the brain, you're mostly seeing the cerebral cortex. This is the wrinkly outer layer. It’s what makes us "us." It handles language, logic, and that weird ability we have to worry about what we said to a barista three years ago.

The Cerebrum and its lobes

The "wrinkles" have names: gyri (the bumps) and sulci (the grooves). They exist because evolution had a space problem. The human skull is only so big, but we needed more surface area for neurons. So, the brain folded in on itself.

- Frontal Lobe: This is the executive suite. It’s right behind your forehead. If you’re looking at pictures of the brain parts and see the very front section, that’s where your personality, decision-making, and motor control live.

- Parietal Lobe: Located at the top and back. It’s the "sensory mall." It processes touch, pressure, and where your body is in space.

- Temporal Lobe: Tucked by your ears. It’s not just for hearing; it’s a massive filing cabinet for memories.

- Occipital Lobe: At the very back. Ironically, the parts that process what you see are as far away from your eyes as possible.

The "Little Brain" at the back

Down at the base sits the cerebellum. In a lot of photos, it looks like a separate attachment, almost like a parasite clinging to the bottom of the main brain. It’s incredibly dense. Even though it's small, it contains about half of the brain's total neurons. It’s the reason you can walk without thinking about it or play a guitar. It’s the master of timing.

What real pictures tell us about "Grey Matter" vs "White Matter"

We always hear about "using your grey matter." In real-life photographs, the difference is stark. Grey matter is the "bark" of the brain—the cell bodies where the processing happens. White matter is the wiring.

The white appearance comes from myelin, a fatty sheath that acts like insulation on a copper wire. Without it, the electrical signals in your brain would move at a crawl. When you see a cross-section of a brain—a "coronal slice"—it looks like a marbled steak. The dark edges are the processors; the white center is the high-speed internet.

Modern neuroimaging, specifically through projects like the Human Connectome Project, has shifted our focus from "what does this part look like?" to "how is this part connected?" We are finding that many disorders, from depression to ADHD, aren't necessarily about a "broken" part. Often, the parts look fine. The issue is in the wiring—the white matter tracts that link them.

The deep stuff: The Limbic System and Brainstem

If you peel back the cortex, you get to the "lizard brain." This is a bit of a misnomer, but it sticks because these parts are evolutionary ancient.

- The Thalamus: It’s the relay station. Almost every piece of sensory info (except smell) goes through here before it hits the cortex.

- The Hippocampus: Shaped like a seahorse. It’s essential for turning short-term experiences into long-term memories. In Alzheimer’s patients, this is often one of the first areas to show visible shrinking in MRI scans.

- The Brainstem: The most critical part. It controls breathing, heart rate, and sleeping. If you see a picture of the brain parts and the brainstem is damaged, the prognosis is usually the worst. It’s the "keep the lights on" department.

How to actually read a brain scan

If you're looking at a functional MRI (fMRI), those glowing orange and blue spots aren't actually "thoughts." They are proxies for oxygenated blood flow. When a part of the brain works hard, it needs more fuel. The scanner picks up where the blood is rushing.

It's a lagging indicator. It’s like looking at a thermal map of a house to see which room the people are in. You see the heat, not the person. This is why "brain pictures" in the news are often over-hyped. A headline might say, "Scientists find the 'Love' part of the brain!" based on one glowing spot. In reality, that spot might just be part of a much larger circuit involved in reward, attention, and physiological arousal.

Actionable insights for the curious mind

Don't just look at a diagram and think you've "seen" the brain. If you want to understand these structures better, use these strategies:

- Look for 3D Slicers: Use tools like the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain. It lets you rotate the structures. You’ll realize the brain isn't flat; it’s a complex, 3D puzzle where parts wrap around each other in ways a 2D image can't capture.

- Study the "Connectome": Search for DTI (Diffusion Tensor Imaging) photos. They look like colorful neon hair. These are the most accurate representations of how information actually moves.

- Mind the Scale: Remember that a single "part" like the primary motor cortex contains millions of neurons. Every pixel in a brain image is actually representing a massive city of activity.

- Check the Source: Real medical images (CT, MRI, PET) look grainy and "ugly" compared to digital illustrations. If it looks too perfect, it’s a model, not a reality.

Understanding pictures of the brain parts is about moving past the labels. It's about seeing the brain as a dynamic, changing organ that rewires itself every time you learn something new. The map is not the territory. The labels are just our best guess at naming the storm. To get a true sense of your own anatomy, look for "tractography" images—they show the beauty of the connections, which is where the real "you" actually lives.