You’re staring at a grainy, black-and-white image on a computer screen in a dim doctor’s office. It looks like a Rorschach test or maybe a topographical map of a very dark planet. Your shoulder hurts—badly—and you’re looking for answers in those blurry shapes. Understanding pictures of rotator cuff anatomy isn't just for orthopedic surgeons; it’s for anyone who wants to know why they can't reach the top shelf anymore without a wince. Honestly, most people expect to see a clean "snap" like a broken rubber band when they look at these images, but the reality is way messier.

It’s complicated.

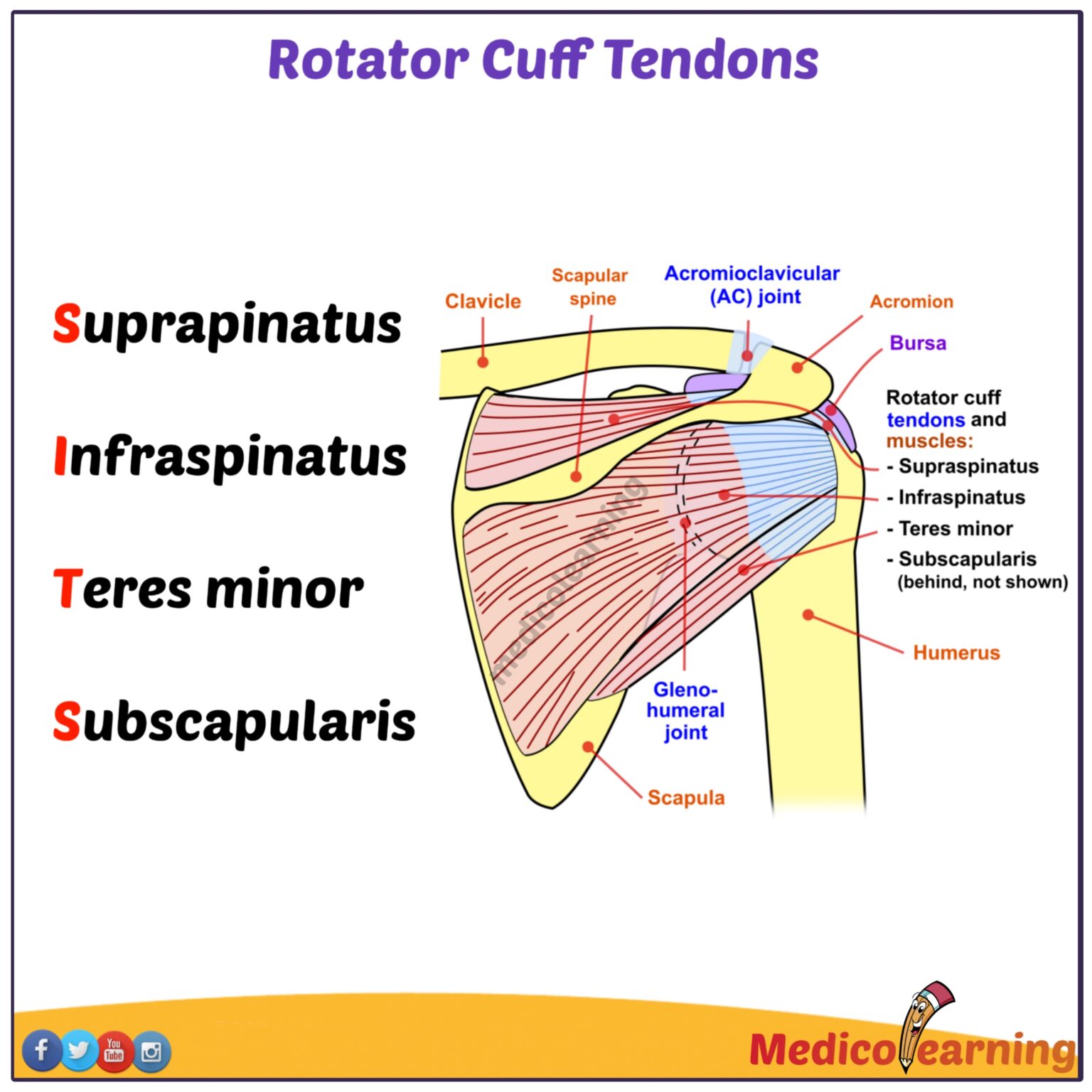

Your rotator cuff isn't just one thing. It is a functional unit of four muscles and their tendons: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. They wrap around the head of your humerus (the "ball") and tuck it into the glenoid (the "socket"). When you look at an MRI or an ultrasound, you’re looking for the continuity of these tissues. A "hole" or a dark gap where there should be bright white or grey fibers usually spells trouble. But here is the kicker: plenty of people have "bad" pictures and zero pain.

Deciphering the Anatomy: What the Camera Sees

When we talk about pictures of rotator cuff injuries, we are usually looking at three different types of imaging technology. X-rays are basically useless for the cuff itself because they only show bone. If your doctor only takes an X-ray, they’re just checking to see if your humerus is sitting too high, which might suggest a massive tear, but they can't actually see the "meat" of the issue.

You need the MRI. This is the gold standard.

In a T1-weighted MRI image, the tendons usually appear as dark, crisp bands. They look like a tight bridge connecting muscle to bone. When a radiologist looks at these, they are hunting for "high signal intensity." That’s doctor-speak for "white spots." In a fluid-sensitive scan, water (edema or inflammation) glows bright white. If that white glow is inside the dark tendon, it’s probably a partial tear or tendinosis. If the white glow goes all the way through the tendon, that’s a full-thickness tear.

🔗 Read more: Why Having Sex in Bed Naked Might Be the Best Health Hack You Aren't Using

Then there’s ultrasound. It’s cheaper and faster. Some sports docs, like those at the Mayo Clinic, love it because they can move your arm while they watch the screen. It's dynamic. You can see the tendon "bunching up" or "snagging" under the acromion bone in real-time. It’s pretty cool, but it’s also highly dependent on how good the technician is. A bad tech can make a healthy shoulder look like a disaster.

The Great Disconnect: Why Your Image Isn't Your Destiny

Let's get real for a second. There is a massive gap between what an image shows and how a person feels. A landmark study published in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery found that a huge percentage of people over age 60 have full-thickness rotator cuff tears on their MRIs but have absolutely no symptoms. They’re playing tennis and lifting grandkids without a care in the world.

Why?

Because the body is incredibly adaptable. If a tear happens slowly over twenty years—what we call a degenerative tear—the other muscles often just take over the workload. Your brain recalibrates. It’s only when the "picture" shows an acute, traumatic tear (like falling off a ladder) that the image and the pain usually match up perfectly. This is why you shouldn't freak out when you read your radiology report. Words like "fraying," "desiccation," or "mild hypertrophy" sound scary, but they’re often just the "wrinkles" of the inside of your body.

We all get them as we age. It's just part of the deal.

💡 You might also like: Why PMS Food Cravings Are So Intense and What You Can Actually Do About Them

Identifying Specific Tears in Professional Imaging

If you are looking at a cross-section of a shoulder, the supraspinatus is the one that usually gives out first. It’s the workhorse. It sits right on top. In pictures of rotator cuff pathology, you’ll often see this tendon looking "thinned out" right where it attaches to the bone—an area called the footprint.

- Partial-thickness tears: These look like a frayed rope. The tendon is still attached, but some of the fibers are pulled away. It might be on the "bursal side" (top) or the "articular side" (bottom).

- Full-thickness tears: This is a literal hole. In a "retracted" tear, the muscle actually pulls the tendon back toward the neck like a snapped window shade.

- Massive tears: This involves two or more tendons. On a scan, the ball of the shoulder (humerus) often starts migrating upward because there’s nothing holding it down anymore.

I’ve seen patients look at their own MRIs and point to a dark spot, thinking it's a tumor or a hole. Usually, it's just a blood vessel or a normal anatomical variant. This is why "Dr. Google" is a dangerous game. You need a trained eye to tell the difference between a subacromial bursa (a normal fluid-filled sac) and a pathological collection of fluid.

The Role of Inflammation and "The Impingement Myth"

For decades, we thought the bone (the acromion) was "hooked" and poking the tendon. We called it impingement. Pictures of the shoulder often showed a tiny bone spur, and surgeons would rush in to shave it down.

Recent research, including large-scale trials in the UK (the CSAW trial), has shown that shaving the bone doesn't actually do much more than a placebo or good physical therapy.

The "picture" showed a spur, so we blamed the spur. But it turns out the tendon was usually failing from the inside out due to poor blood supply or overuse, not because a bone was stabbing it. This shift in thinking has changed how we interpret those pictures of rotator cuff issues. We focus less on the "space" and more on the quality of the tissue itself. Is the muscle turning into fat? That’s called fatty infiltration. If the MRI shows a lot of white streaks inside the muscle belly, that’s a bad sign. It means the muscle hasn't been used in so long that it's literally turning into lard. At that point, surgery might not even work because there's no "engine" left to pull the tendon.

📖 Related: 100 percent power of will: Why Most People Fail to Find It

Beyond the Still Image: Moving Toward Recovery

If you’ve got the images and you’ve got the pain, what now?

You don't just treat the picture; you treat the person. If your MRI shows a small tear but you still have a full range of motion, surgery is probably a bad idea. Cortisone shots can help with the "fire" in the shoulder, but they don't fix the tear. In fact, some studies suggest too many shots can actually weaken the tendon further.

Physical therapy is the real MVP here. By strengthening the "rotator cuff's neighbors"—the serratus anterior, the traps, and the rhomboids—you can take the pressure off the injured site. It’s about biomechanics. You’re teaching your shoulder how to move again without pinching the damaged bits.

Sometimes, though, the picture is too far gone. If there is a "full-thickness, retracted tear" in a young, active person, that’s usually a surgical case. The goal is to "anchor" that tendon back to the bone using tiny screws (anchors) and high-strength sutures.

Actionable Steps for Managing Your Diagnosis

- Get the Report, Not Just the CD: Most people get a disc with the images. Unless you're a radiologist, you won't see much. Ask for the written "impression" at the bottom of the radiologist's report. That’s the summary.

- Test Your Function: Can you lift your arm out to the side (abduction)? Can you rotate it outward (external rotation)? If you can do these things despite a "tear" on the image, your situation is likely manageable without a scalpel.

- Check for Fatty Infiltration: Ask your doctor specifically if there is "atrophy" or "fatty changes" in the muscles. This is the most important prognostic factor for whether a repair will actually hold.

- Prioritize Posterior Capsule Stretching: Often, the pain isn't from the tear itself but from the "tightness" that develops around it. Simple "sleeper stretches" can change the mechanics of the joint enough to bypass the pain.

- Look for Fluid: If the report mentions "significant joint effusion" or "subacromial bursitis," your immediate problem is inflammation. Addressing the chemistry of the shoulder (via NSAIDs or ice) is the first step before you worry about the structural tear.

Ultimately, pictures of rotator cuff damage are just one piece of the puzzle. They are a snapshot in time, not a life sentence. People live full, athletic lives with frayed tendons every single day. The trick is knowing when the image represents a structural failure that needs a fix, and when it’s just the story of a shoulder that has worked hard and needs a little bit of rest and smarter movement.

Don't let a grainy black-and-white photo convince you that you're broken. The human body is significantly more resilient than a digital image suggests. Concentrate on how the shoulder moves and feels, rather than just how it looks on a monitor. Focus on the strengthening, the range of motion, and the gradual return to activity. That is where the real healing happens.

Next Steps for Your Shoulder Health:

Consult with a board-certified orthopedic specialist or a Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) to correlate your imaging results with a clinical physical exam. Focus on a 6-to-12-week trial of structured physical therapy before considering invasive interventions, as many tears—even full-thickness ones—respond remarkably well to conservative loading protocols. Check your imaging report specifically for the "Goutallier grade," which measures muscle quality, to better understand your long-term recovery potential.