You’ve seen the face. Even if you aren't a TCM addict or a Western buff, that craggy, Mount Rushmore profile is etched into the DNA of American cinema. But when you start digging through pictures of Randolph Scott, you quickly realize you aren't just looking at one man. You’re looking at a shapeshifter who managed to pivot from a "pretty boy" socialite to the leathery, stoic embodiment of the Old West.

It's kinda wild how his look evolved. Most people associate Scott with the dusty, saddle-sore hero of the 1950s, but the early archival shots tell a completely different story. Honestly, if you saw a photo of him from 1935 next to one from 1960, you might think they were distant cousins rather than the same guy.

The Early Days: Paramount’s "Adonis" in a Suit

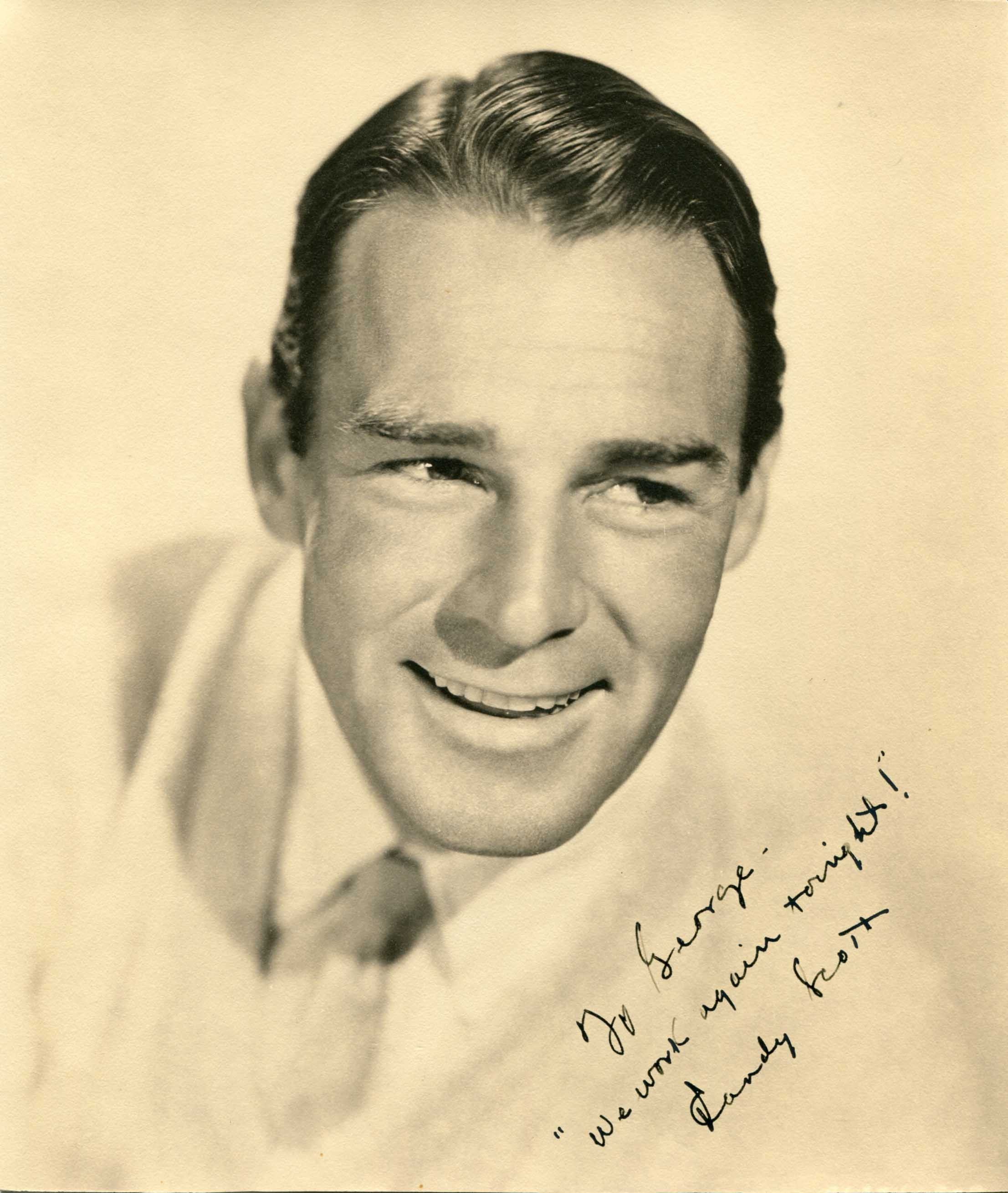

In the early 1930s, Randolph Scott was basically Hollywood's version of a Swiss Army knife. He was tall—6'2"—lanky, and had this courtly Southern drawl that made directors want to put him in tuxedos. If you find pictures of Randolph Scott from this era, like his stills from Roberta (1935) or Follow the Fleet (1936), he looks polished. Almost too polished.

He was the "other guy" in the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musicals. He played the handsome romantic interest who didn't have to dance because his face did all the heavy lifting. There’s a famous series of publicity shots from his time at Paramount where he’s leaning against a fireplace or holding a golf club. He looks like he belongs in a country club, not a canyon.

But even then, there was a stiffness to him. Critics at the time sometimes called him "lumbering." He hadn't quite grown into his skin yet. It wasn't until the camera started catching him in natural light, away from the artificial glow of the soundstage, that the "real" Scott began to emerge.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

That Famous Housemate: The Cary Grant Photos

You can't talk about Scott’s visual history without mentioning the "Bachelor House" photos. For years, Scott shared a beach house in Santa Monica with Cary Grant. The two were best friends, and the candid pictures of Randolph Scott and Grant from the 1930s are legendary among film historians.

They show a side of Scott that was rarely seen on screen:

- Scott and Grant tossing a medicine ball in the backyard.

- The pair lounging by the pool in matching swimwear.

- Casual breakfast shots that look like they belong in a modern lifestyle magazine.

These images have fueled decades of rumors about their relationship, but regardless of what you believe, the photos represent a specific moment in Hollywood history. They show a relaxed, domestic side of a man who would later become the ultimate symbol of rugged solitude.

The Weathering: Why 1950s Randolph Scott Hits Different

Something happened after World War II. Scott turned 50 in 1948, and as he aged, his face became his most powerful tool. The "Ranown Cycle" films—the ones he made with director Budd Boetticher—are where the most iconic pictures of Randolph Scott come from.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

Think about the close-ups in The Tall T (1957) or Ride Lonesome (1959). His skin looks like expensive luggage. It’s lined, sun-scorched, and absolutely fascinating. He stopped trying to be the "leading man" in the traditional sense and started being a force of nature.

"He was the quintessential screen cowboy because he looked like he’d actually lived through a dust storm." — Film historian observation.

By this point, Scott had his own production company, Ranown. He had total control over his image. He chose to wear the same hat, the same belt, and often the same dusty clothes across multiple films. He knew what worked. When you see a photo of him from Comanche Station (1960), you aren't looking at an actor; you're looking at a man who seems to have been born on a horse.

Where to Find Authentic Archival Shots

If you're a collector or just a fan, knowing where the "good stuff" is hidden matters. You can't just rely on blurry Google Image results.

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

- The UCLA Library Special Collections: They hold the actual Randolph Scott papers. This includes 19 linear feet of photos, film stills, and personal scrapbooks donated by his daughter, Sandra Scott Tyler.

- The Alamy and Getty Archives: For high-resolution press photos from the 1940s, these are the gold standard. You can find rare stills from his "B" Westerns that haven't been seen in decades.

- The "50 Westerns from the 50s" Blog: This is a niche but incredible resource for seeing how Scott's movies were advertised in local newspapers. The lobby card scans are beautiful.

The Final Frame: Ride the High Country

The most poignant pictures of Randolph Scott come from his very last film, Ride the High Country (1962). He was 64 years old. He starred alongside Joel McCrea, and the photos from that set are a masterclass in aging with dignity.

There’s a specific shot of him and McCrea riding together through the Sierra Nevada mountains. Scott looks elegant but exhausted. He retired immediately after that movie, despite it being one of his best-reviewed performances. He walked away while he was still at the top, spending the next 25 years playing golf and managing his massive real estate empire. He was one of the few actors who actually got rich and stayed rich, eventually becoming a multimillionaire.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Collectors

If you are looking to start a collection of Scott memorabilia or just want to appreciate his work better, here is how you should approach it:

- Look for "Lobby Cards" over standard prints: Lobby cards were the 11x14 posters used in theater foyers. They often used better color processing (like Cinecolor) than the films themselves.

- Focus on the 1956-1960 window: This is the peak "Ranown" era. These images carry the most "Western" aesthetic.

- Verify the source: Many "signed" photos of Scott are actually secretarial or autopen. Real Randolph Scott signatures are rare because he was famously private and disliked the "celebrity" machine.

Basically, the journey of Scott's face is the journey of the Western genre itself—moving from the flashy, romanticized myths of the 1930s to the gritty, morally complex reality of the late 1950s. Whether he’s in a tuxedo with Cary Grant or a Stetson in the Mojave Desert, the man knew how to hold a frame.

To truly appreciate the evolution of his career, your next step should be to track down a high-quality restoration of Seven Men From Now. Seeing those "leather-faced" close-ups in motion provides a context that a still photograph just can't capture.