Ever looked at a photo of Ernest Hemingway and felt like he was staring right through you? Most people have a very specific image in their head when they think of "Papa." It’s usually the grizzled old lion with the white beard, wearing that chunky turtleneck sweater, looking like he just stepped off a boat or out of a fight.

Honestly, that’s just one version of the story.

When you dig into the massive archive of pictures of Ernest Hemingway, you start to see a guy who was constantly performing for the camera. He wasn't just a writer; he was a brand before "personal branding" was even a thing. But if you look closely at the edges of those frames—the 1923 passport photo or the blurry shots of him in a Milan hospital bed—you see a very different man. You see the cracks in the armor.

The Sweater That Wasn't What It Seemed

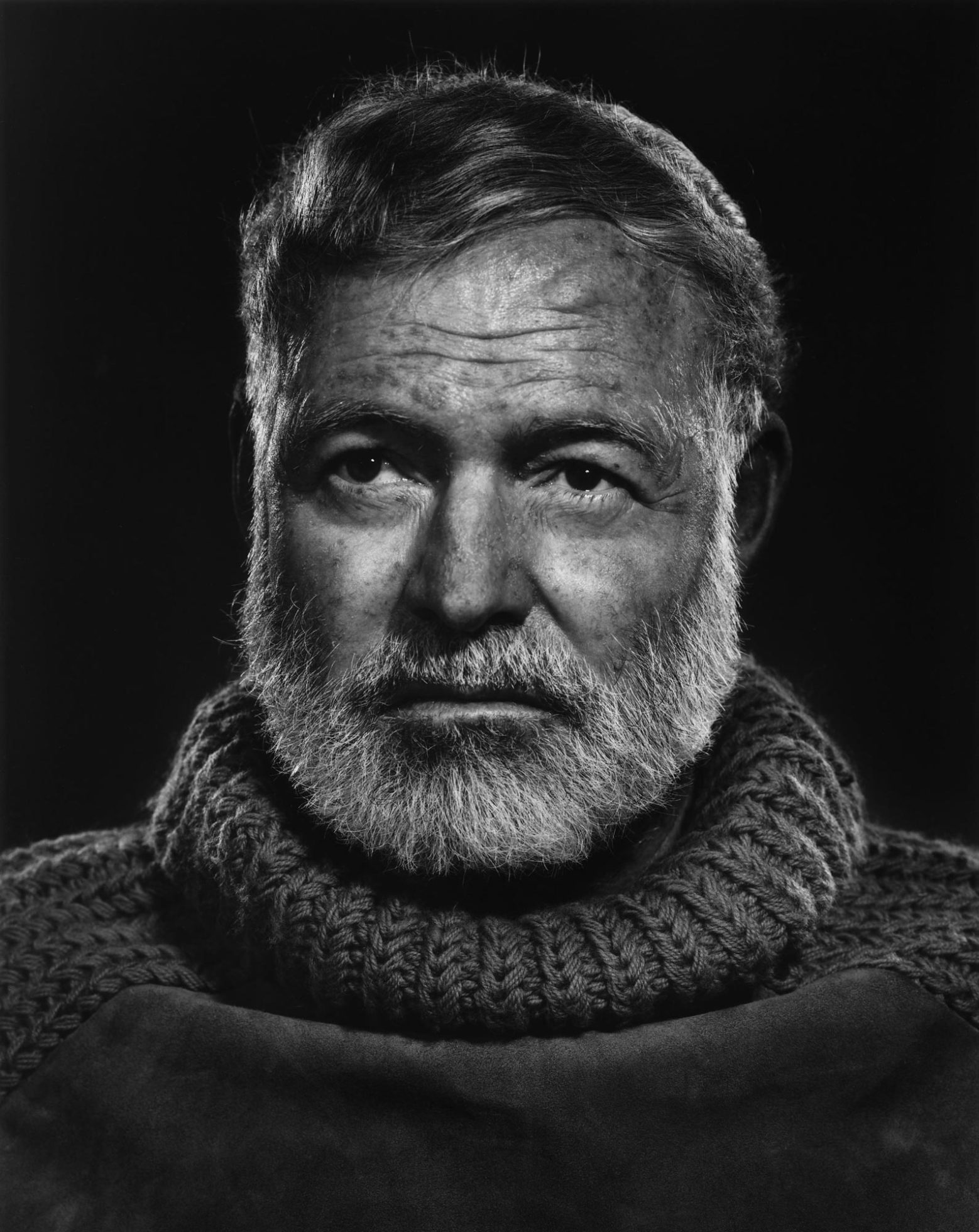

Let’s talk about the most famous photograph of them all. You know the one. It was taken by Yousuf Karsh in 1957. Hemingway is in his late fifties, his hair is snow-white, and he’s wearing a thick, cable-knit sweater that screams "rugged outdoorsman."

Here is the kicker: that sweater wasn't some salt-crusted garment he used for hauling marlin on the Pilar. It was a high-fashion piece from Christian Dior. His fourth wife, Mary, had bought it for him in Paris.

Karsh, the photographer, actually expected to meet a "he-man" archetype. Instead, he found a guy he described as having a "peculiar gentleness." Hemingway had recently survived two—yes, two—plane crashes in Africa. He was in constant pain. His kidneys were failing. He had a massive concussion.

When you see that picture now, look at his eyes. One eye looks like it belongs to a hunter, sharp and focused. The other? It looks like the eye of the hunted. It’s a portrait of a man holding himself together by a thread, yet it became the ultimate symbol of masculine strength. Talk about irony.

✨ Don't miss: Mia Khalifa New Sex Research: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessed With Her 2014 Career

The "Handsome Youth" Nobody Recognizes

Before he was Papa, he was just Ernie from Oak Park. If you stumble across the pictures of Ernest Hemingway from his time in Paris in the early 1920s, you might not even recognize him.

He was incredibly handsome.

In his 1923 passport photo, he has a thick, dark mustache and a look of absolute, unearned confidence. He was a starving journalist for the Toronto Star, living in a cold-water flat, but he looked like a movie star. This was the Hemingway who boxed in gyms with Ezra Pound and went to the horse races with Gertrude Stein.

There’s a specific energy in these early shots. It’s a "pre-war" (or at least, pre-fame) vitality. He hadn't yet become a caricature of himself. He was just a guy trying to write "one true sentence."

The Evolution of the Persona

It’s fascinating to track how the camera changed him. By the 1930s, the mustache was gone, replaced by the beginnings of the beard. The suits were replaced by safari jackets and fishing vests.

- The War Correspondent: Photos from the Spanish Civil War show him with Robert Capa. He looks intense, muddy, and genuinely in his element.

- The Big Game Hunter: The 1934 safari photos are where the "tough guy" myth really solidifies. He’s posing with water buffalo and lions. He looks like he’s living a Life magazine spread because, well, he often was.

- The Cuban Exile: By the 1940s at Finca Vigía, he’s often shirtless, surrounded by cats. He looks relaxed, but there’s a bloat starting to show from the heavy drinking that would eventually define his later years.

Why the Candid Shots Matter More Than the Portraits

While the Karsh portrait is the one that sells posters, the candid pictures of Ernest Hemingway tell the more human story.

🔗 Read more: Is Randy Parton Still Alive? What Really Happened to Dolly’s Brother

There’s a photo of him in 1918, recuperating in an Italian hospital after being peppered with mortar shrapnel. He’s sitting in a wheelchair, grinning like a kid who just got away with something. He was 19. He had just fallen in love with Agnes von Kurowsky, the nurse who would break his heart and inspire A Farewell to Arms.

Compare that to the shots taken by Alfred Eisenstaedt in Cuba in 1952. Eisenstaedt called Hemingway the "most difficult man" he ever photographed. He described him as paranoid, "booze-sodden," and prone to shouting.

In those 1952 shots, the bloat is real. The "lion" looks tired. You can see the physical toll of a life lived at 100 miles per hour. It’s a reminder that the camera can be a cruel witness. It catches the decline that the prose tries to hide.

The Archival Goldmine: Where to Find the Real Stuff

If you're actually looking to see these for yourself, don't just stick to Google Images. The real treasure is in the archives.

The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston holds the "Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection." We’re talking over 10,000 still images. It covers everything from his childhood in Michigan to his final days in Ketchum, Idaho.

Another great spot is the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. They have about 1,500 images that lean heavily into his family life and his parents’ travels. Seeing him as a toddler—Grace Hall Hemingway used to dress him in girls' clothes, which was a weird Victorian trend—is a trip. It explains a lot about his later obsession with extreme masculinity.

💡 You might also like: Patricia Neal and Gary Cooper: The Affair That Nearly Broke Hollywood

Sorting Fact from the "Papa" Fiction

People love to romanticize the pictures of Ernest Hemingway, but we have to be honest about what we’re seeing.

He was a master of the "pose." Whether he was holding a shotgun or a pen, he knew how to angle his head. He knew the camera was watching. He was one of the first writers to realize that his life—the fishing, the bullfights, the wives—was just as much a product as the books were.

But as his health failed in the late 50s, the "mask" slipped. The late photos taken in Sun Valley are hard to look at. He’s thin, his skin is papery, and the spark in his eyes is gone. He looks like a stranger to the man in the Dior sweater.

How to Analyze Hemingway's Visual Legacy

If you're studying these photos for a project or just because you’re a fan, try these steps to get more out of them:

- Check the Eyes: Ignore the props (the guns, the fish, the booze). Look at his expression. Is he looking at the photographer, or past them?

- Look at the Surroundings: The background often tells you who he was trying to be that day. Is he in a high-end hotel or a dusty camp?

- Compare Eras: Put a photo from 1922 next to one from 1959. The physical transformation is one of the most dramatic in literary history.

The visual record of Hemingway is basically a map of the 20th century. It moves from the optimism of the "Lost Generation" to the gritty reality of World War II, and finally to the fractured, paranoid dawn of the 1960s.

Next time you see a picture of him, don't just see the "tough guy." Look for the kid from Oak Park who was scared of the dark. Look for the artist who was terrified he’d lost his talent. That’s where the real Ernest Hemingway is hiding.

Start by visiting the digital archives of the JFK Library. They’ve digitized a huge portion of their collection, allowing you to zoom in on the details—the labels on his wine bottles, the titles on his bookshelves, and the look in his eyes when he thought no one was watching. It’s the closest we’ll ever get to the man behind the myth.