You’re squinting at your phone screen, trying to figure out if that fuzzy yellow thing on the screen door is a friendly neighborhood pollinator or a flying needle with a grudge. It happens to everyone. We see a flash of yellow and black and our primate brains immediately scream "danger." But if you actually look at high-quality pictures of bees and wasps, the differences aren't just subtle; they are massive structural shifts that tell a story about how these insects live, eat, and defend themselves. Most people think it’s just about the "fuzz," but honestly, it’s deeper than that.

Identifying these insects isn't just a fun trivia game. It matters for your garden, your safety, and frankly, for the survival of species that are currently struggling. When people misidentify a harmless Mason bee as a yellowjacket, the results are usually bad for the bee.

The Anatomy of the Shot

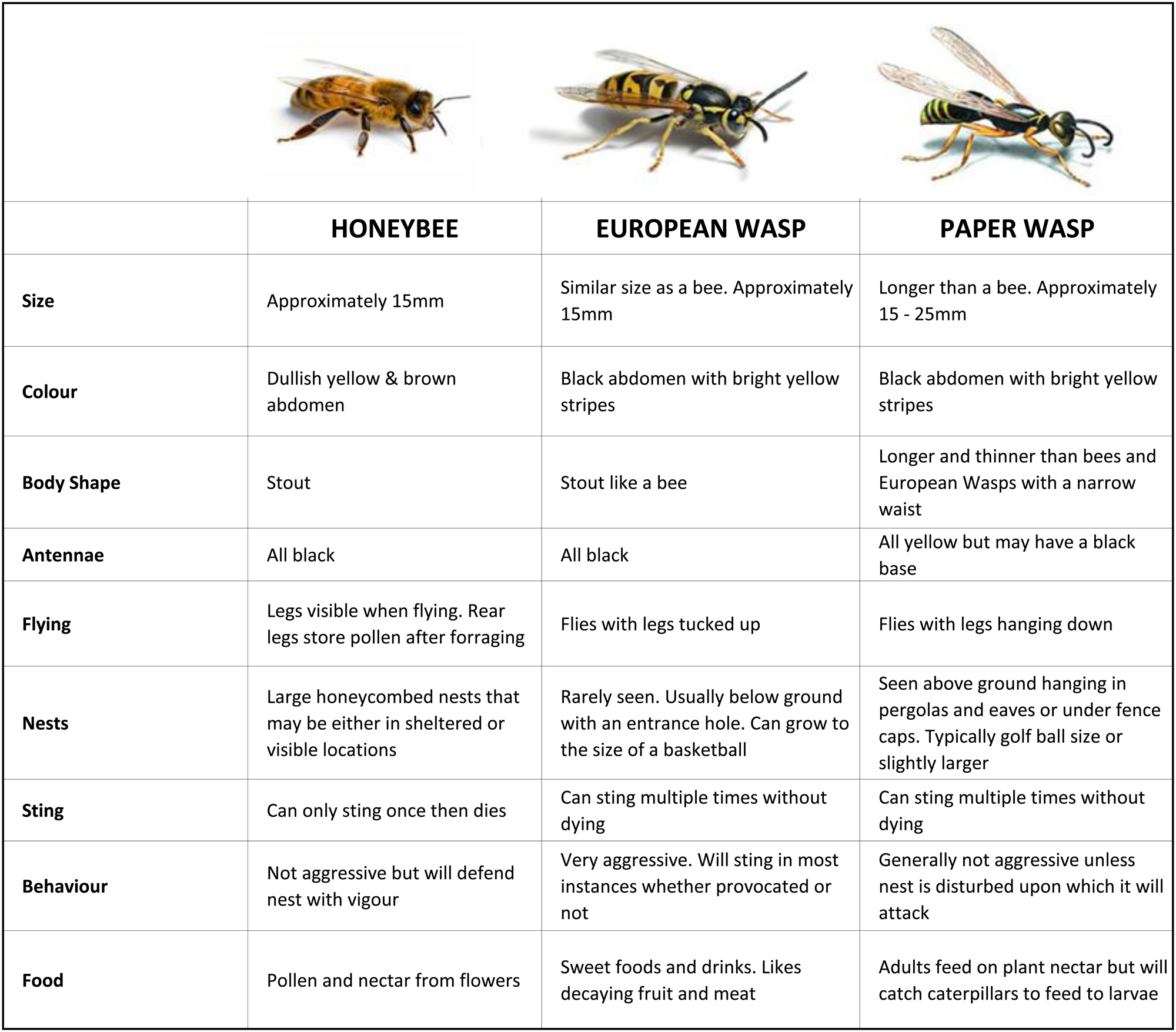

Taking or viewing pictures of bees and wasps requires a bit of an eye for detail. Look at the waist. That’s the "tell." Wasps have what entomologists call a petiole—a tiny, cinched waist that looks like they’re wearing a corset that’s three sizes too small. Bees? Not so much. Bees are built like tanks. They are robust, stout, and generally have a much more integrated thorax and abdomen.

Check out the legs too. If you see an insect in a photo with big, wide, flattened hind legs, you’re looking at a bee. Specifically, you’re likely looking at a honeybee or a bumblebee with "pollen baskets" (corbiculae). Wasps don't have these. Their legs are spindly, hanging down like landing gear on a helicopter. It's these tiny morphological differences that professional photographers like Piotr Naskrecki capture to show us the "alien" world right in our backyards.

Why Do We Get Them Confused?

Evolution is a copycat. It's called Batesian mimicry. There are flies—specifically Hoverflies—that look exactly like wasps. They do this so birds won't eat them. So, when you’re browsing through pictures of bees and wasps, you might actually be looking at a fly that’s just really good at cosplay.

The "scary" factor plays a role here too. We’ve been conditioned to fear the sting. Because of this, our brains tend to over-generalize. We see a yellowjacket (a type of wasp) and we project that aggressive behavior onto the docile sweat bee. It's a classic case of a few bad actors ruining the reputation of the entire group. Wasps are predators; they hunt other insects. Bees are vegetarians; they just want your lavender and sunflower nectar.

The Fuzzy Factor and Beyond

Bees are covered in branched hairs called plumose hairs. If you zoom in on macro pictures of bees and wasps, the bee hairs look like tiny feathers. This is an evolutionary masterstroke for collecting pollen. The pollen grains get stuck in those "feathers" through static electricity. It's basically magic.

💡 You might also like: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Wasps, on the other hand, look like they’ve been waxed. They have very few hairs, and the ones they do have are straight and simple. They look shiny and metallic. Think of a polished sports car versus a teddy bear. That’s the visual contrast we're talking about.

- The Honeybee (Apis mellifera): These are the ones most people recognize. They aren't actually native to North America (they’re European), but they are everywhere. In photos, they have a golden-brown hue rather than neon yellow.

- The Common Yellowjacket: This is the "jerk" of the wasp world. They are bright, aggressive yellow and jet black. They love your soda cans. If the photo shows an insect scavaging a piece of ham at a picnic, it's 100% a wasp.

- The Bumblebee: Big, round, and incredibly fuzzy. They are the "pandas" of the insect world. They are so heavy that they have to use "buzz pollination," vibrating their entire bodies to shake pollen loose from flowers like tomatoes.

- Paper Wasps: These have long, dangling legs and build those umbrella-shaped nests under your eaves. They are actually quite chill if you don't poke their house.

Photography as a Conservation Tool

Why do we need more pictures of bees and wasps? Because we can't protect what we can't identify. Groups like the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation rely on "citizen science." When you snap a photo of a bee in your garden and upload it to an app like iNaturalist, you are providing real data points for scientists tracking population declines.

The Rusty Patched Bumble Bee (Bombus affinis) was the first bumble bee to be placed on the endangered species list in the continental U.S. How do researchers find them? Often, it starts with a blurry cell phone picture from a backyard gardener. That's the power of documentation.

Misconceptions That Need to Die

There is this myth that bees die after they sting you. That is only true for honeybees, and only because their stinger is barbed and gets stuck in our thick mammalian skin. Most bees—and almost all wasps—can sting multiple times without any physical cost to themselves.

Another big one: "All wasps are bad." Honestly, wasps are the unsung heroes of pest control. Without wasps, your garden would be overrun by caterpillars and aphids. They are the lions of the insect world, keeping the ecosystem in check. If you see a photo of a wasp carrying a cicada or a spider, don't be grossed out. Be thankful. They are doing the hard work of balancing the food chain.

How to Spot the Difference at a Glance

If the insect is hovering over a flower and looks like a golden nugget, it's a bee.

If it’s darting around your trash can or the eaves of your house with a jerky, aggressive flight pattern, it’s a wasp.

If it’s hovering perfectly still in mid-air and then zipping a few inches to the left, it’s probably a hoverfly pretending to be a wasp.

📖 Related: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

The Art of Capturing These Images

If you’re trying to take your own pictures of bees and wasps, don't use a zoom from far away. Use a macro lens or a macro setting. You need to get close, but don't be erratic. Insects react to fast, sudden movements. If you move slowly—sorta like you're moving through molasses—they usually won't care that you're there. They have jobs to do. They are busy.

Focus on the eyes. Bees have large compound eyes that cover a lot of their head. In some species, like the Carpenter bee, the males have a distinct yellow spot on their face. It looks like a little badge. Seeing that level of detail changes how you view these creatures. They stop being "bugs" and start being individuals with complex lives.

What the Experts Say

Dr. Marla Spivak, a renowned entomologist at the University of Minnesota, often talks about how we've "decoupled" ourselves from the natural world. Looking at pictures of bees and wasps is a way to re-couple. It forces us to pay attention. You start noticing that the "bee" you saw yesterday is different from the one you saw today. You notice that some have long tongues and some have short ones. You notice that some sleep inside flowers at night (yes, really, look for photos of "sleeping globe mallows bees").

Putting the Knowledge to Use

Stop spraying. That’s the biggest takeaway. When you see an insect that looks like a wasp, don't immediately reach for the poison. Look closer. Is it a Mud Dauber? They are solitary, non-aggressive, and they eat black widow spiders. You want them around.

If you're looking at pictures of bees and wasps to help you decide whether to call an exterminator, look at the nest.

- Waxy, hexagonal combs in a hollow tree or wall? Honeybees. Call a local beekeeper; they’ll often come get them for free.

- Paper-like gray structures? Wasps.

- Holes in the ground? Could be yellowjackets (dangerous) or Mining bees (totally harmless).

Identifying the species through visual cues saves lives—both yours and the insects'. We are in the middle of a massive decline in insect biomass globally. We need every pollinator and every predator we can get.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

Actionable Steps for the Amateur Naturalist

Start a digital "field guide" on your phone. Every time you see a stinging insect, take a photo. Use an AI-identifier or a community forum like Reddit’s r/whatsthisbug to get a positive ID.

Study the "Waist and Hair" rule. If you can't see a waist and it's hairy, it’s a bee. If it’s got a "wasp waist" and it’s smooth, it’s a wasp.

Plant a "pollinator pocket" in your yard with native plants. This attracts a wider variety of species, giving you more opportunities to see the diversity beyond just the "big two" (honeybees and yellowjackets).

Check for "pollen pants." If the insect has big clumps of yellow or orange on its back legs, it’s a female bee hard at work. Wasps will never have this.

Understand the "Flight of the Wasp." Wasps often fly with their legs dangling down. Bees tuck theirs in to be more aerodynamic.

By paying attention to these visual markers in pictures of bees and wasps, you move from a place of fear to a place of observation. It’s a much better way to live. You’ll find that the world is a lot more interesting when you aren't terrified of every buzz you hear.