You’re sitting in a cold exam room and the doctor turns the monitor around. There’s a grainy, black-and-white blob. They point to a shadow and say you have a hiatal hernia. Honestly, to most of us, it just looks like a weather map from the eighties. But understanding those pictures of a hiatal hernia is actually the first step in figuring out why your chest feels like it’s on fire every time you eat pizza. It’s not just a medical abstraction. It’s a physical structural change in your torso.

A hiatal hernia happens when the upper part of your stomach pushes through the hiatus. That’s just a fancy word for the small opening in your diaphragm where the esophagus passes through. Usually, the diaphragm acts as a tight seal. When that seal fails, the stomach decides to migrate north. It’s a weird concept. Your stomach belongs in your abdomen, but suddenly, a piece of it is hanging out in your chest cavity, crowded right next to your heart and lungs.

What do doctors actually look for in these images?

When a radiologist looks at pictures of a hiatal hernia, they aren't looking for a "growth" or a tumor. They are looking for a displacement. Imagine a sock being pulled through a small ring. If part of the sock stays bunched up above the ring, that’s your hernia.

The Barium Swallow (The "Action" Movie)

This is probably the most common way people see their hernia. You drink a thick, chalky liquid that tastes like metallic strawberries. As you swallow, a technician takes X-rays in real-time. This is called fluoroscopy. In these pictures, the barium glows bright white. You can see the liquid travel down the esophagus, and instead of a straight line into the stomach, you’ll see a "pouch" or a bulbous shape resting above the diaphragm line.

Doctors like Dr. David Katz at Yale have often noted that the size of the hernia in the picture doesn't always correlate to how miserable you feel. You could have a massive "paraesophageal" hernia—where the stomach crawls up alongside the esophagus—and feel nothing. Or, you could have a tiny "sliding" hernia that barely shows up on a scan but makes you feel like you're swallowing ground glass.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Right Care at Texas Children's Pediatrics Baytown Without the Stress

Endoscopy: The Interior View

If you’ve had a camera snaked down your throat, you’ve seen the "inside" pictures. This is an EGD (Esophagogastroduodenoscopy). The view is pink and wet. The doctor is looking for the "Z-line," which is the junction where the esophagus tissue meets the stomach tissue. If that line is significantly higher than the diaphragmatic pinch, they snap a photo. That’s your hiatal hernia caught on camera. These images also show the damage, like esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus, which looks like angry, red, irritated patches on the lining.

Why the type of image matters for your treatment

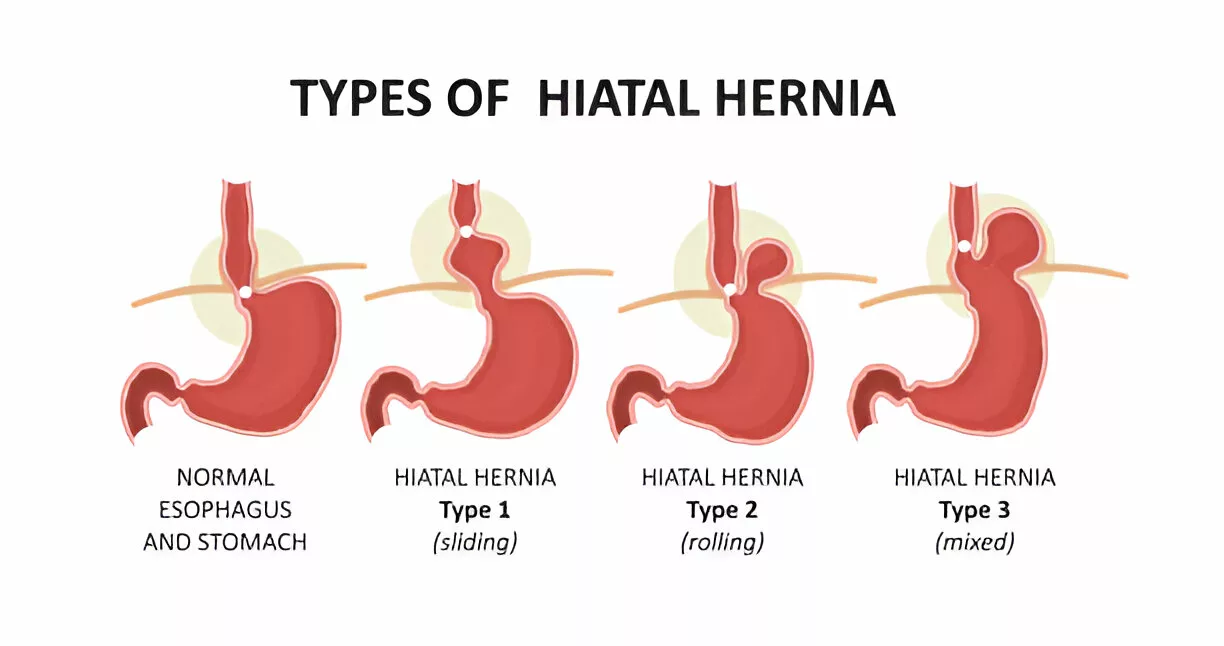

Not all hernias are created equal. You’ve basically got two main flavors. The sliding hiatal hernia is the most common. It’s transient. It moves up and down. One day it’s in the picture, the next day it might be tucked back where it belongs. This makes them notoriously "shy" during exams.

Then you have the paraesophageal hernia. These are the ones that look more dramatic on CT scans. The stomach isn't just sliding; it's bunching up next to the esophagus. These are the ones that make surgeons nervous because they can get "strangled," cutting off blood supply. If your scan shows the stomach tilted or rotated, that’s a red flag for "volvulus," which is basically a twisted stomach. It sounds terrifying. It is serious.

The "Invisible" Symptoms and Scan Limitations

Sometimes the pictures of a hiatal hernia are clear as day, but the symptoms are weird. Most people expect heartburn. But did you know a hiatal hernia can cause heart palpitations? It’s called Roemheld Syndrome. Because the stomach is sitting in the chest, it can physically irritate the vagus nerve or even press against the atrium of the heart after a big meal.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Healthiest Cranberry Juice to Drink: What Most People Get Wrong

I've talked to patients who went to the ER thinking they were having a heart attack. The EKG was fine. The blood work was fine. It wasn't until a chest X-ray showed a "retrocardiac air-fluid level"—which is just doctor-speak for "your stomach is behind your heart"—that they got an answer.

Why scans sometimes miss it

- The "Sliding" Factor: If you're standing up during the X-ray, gravity might pull the hernia down.

- Empty Stomach: Most scans require fasting, which means your stomach is small and less likely to protrude.

- Breath-holding: Deep breaths change the pressure in your chest, sometimes hiding the hernia during the exact moment the "shutter" clicks.

Can you "see" it from the outside?

Short answer: No. You can't look in the mirror and see a hiatal hernia. It's too deep. This isn't like an umbilical or inguinal hernia where you get a visible bulge under the skin. If you have a bulge in your upper abdomen, it’s likely an epigastric hernia, which is a totally different beast involving the abdominal wall, not the diaphragm.

The only way to "see" it is through medical imaging. If you're looking at your own lab reports, keep an eye out for terms like "hiatal laxity" or "Patulous hiatus." Those are the early warning signs that the opening is widening, even if the stomach hasn't fully made its move yet.

What you should do after seeing your results

Seeing those pictures of a hiatal hernia can be a bit overwhelming. You see this thing that shouldn't be there and you want it out. But surgery is usually the last resort. Most people manage this through lifestyle tweaks that are boring but effective.

💡 You might also like: Finding a Hybrid Athlete Training Program PDF That Actually Works Without Burning You Out

- Stop the "Big Meal" habit. Your stomach is cramped for space now. If you overfill it, the pressure has nowhere to go but up into your chest.

- Gravity is your best friend. If your scans show a significant slide, sleeping on a wedge pillow (at least 6 inches of elevation) keeps the stomach contents from migrating into your throat while you sleep.

- Watch the "Intra-abdominal Pressure." This means no heavy lifting or intense core crunches right after eating. You’re basically squeezing a tube of toothpaste with the cap off.

- The "Water Load" Test. Some functional doctors use a "water load" and a tilt table to see how much volume the hernia can handle before it causes reflux.

If your imaging shows a very large hernia (Stage III or IV), you might be looking at a Nissen Fundoplication. That’s where they wrap the top of the stomach around the esophagus to create a new valve. It’s a major move. Surgeons like those at the Mayo Clinic usually only recommend this if you're aspirating acid into your lungs or if the hernia is so big it’s compromising your breathing.

The reality is that many people over 50 have these images in their medical files and don't even know it. It becomes an "incidental finding." You went in for a rib injury, and the doctor says, "By the way, you’ve got a hiatal hernia." If it’s not causing symptoms, many experts suggest just leaving it alone. The human body is surprisingly good at compensating for these structural shifts until it isn't.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Request your actual imaging files. Don't just read the report. Ask for the CD or the portal access to see the "barium swallow" images yourself.

- Identify the "Z-line" height. If your endoscopy report mentions the Z-line is more than 2cm above the diaphragm, that's a confirmed hiatal hernia.

- Track the triggers. For two weeks, note if your pain is "positional." If it hurts more when bending over to tie your shoes, that’s a classic sign of the stomach sliding upward.

- Consult a GI specialist specifically about "Manometry." This test measures the pressure and muscle contractions in your esophagus to see if the hernia is affecting your ability to swallow, which the pictures can't always tell you.