If you’ve ever looked at pics of transverse waves in a textbook, you’ve probably seen that same perfect, curvy line. It looks like a mountain range made of light or a jump rope frozen in time. It’s clean. It’s simple. It’s also kinda misleading because reality is messy. Most people see those diagrams and think they understand how light or seismic activity works, but there is a massive gap between a static 2D drawing and the way energy actually moves through our universe.

Waves are everywhere. They are the reason you can see this screen and the reason your cell phone picks up a signal in the middle of a concrete jungle. But if we’re being honest, the way we visualize them often fails to capture the "why" behind the "what."

Why Most Pics of Transverse Waves Look Like Squiggles

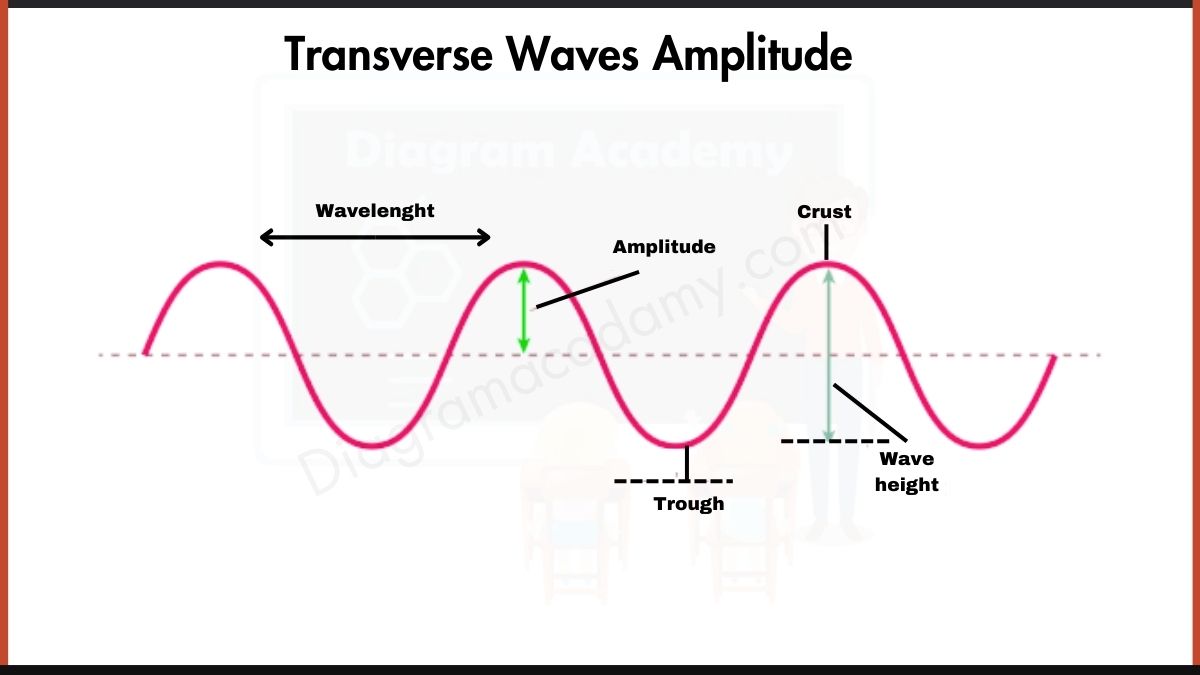

The classic image of a transverse wave is a sine wave. You’ve got your crests—the high points—and your troughs—the low points. In a physics lab, this is easy to show with a Slinky. You lay it flat on a table, shake one end left and right, and watch the "snake" move down the line.

The defining characteristic here is direction. In a transverse wave, the medium moves perpendicular to the direction the energy is traveling. Think about a stadium wave at a baseball game. The fans stand up and sit down (vertical motion), but the "wave" travels horizontally around the park. The fans don't actually move to the next seat; they just bob up and down.

The Geometry of Light

When you search for pics of transverse waves specifically regarding light, things get weird. Light doesn't need a "medium" to travel through. It doesn't need air or water. It’s actually two waves in one: an electric field and a magnetic field. They are locked at 90-degree angles to each other. Most 3D renders show this as a red wave and a blue wave intertwined. It’s beautiful, but it’s just a mathematical model.

We can't actually "see" these fields. We see the result of them hitting our retinas.

The Difference Between a Drawing and a Photograph

There is a huge distinction between a computer-generated diagram and an actual photograph of wave phenomena. If you look at high-speed photography of a guitar string vibrating, it doesn't look like a perfect curve. It looks like a blurry, chaotic mess of harmonics. This is because real-world transverse waves are rarely "pure." They have overtones. They have friction. They have interference from other waves nearby.

Take water waves. Are they transverse? Sort of. Most people think so. Actually, they are a mix of transverse and longitudinal (the ones that push and pull, like sound). If you look at a cross-section photo of a deep-sea swell, the water molecules are actually moving in circles. It’s a hybrid. This is why a simple diagram of a "transverse" water wave is usually a lie of simplification.

Real-World Examples You Can Actually See

The S-Waves of Earthquakes: Seismologists use "Secondary" waves to map the Earth's interior. These are purely transverse. They can't travel through liquid, which is how we figured out the Earth’s outer core is molten. If you look at a seismograph readout, those jagged spikes are the visual representation of the earth literally shearing side-to-side.

Polarized Sunglasses: This is the coolest way to "see" the transverse nature of light. Light from the sun vibrates in every direction. Polarized lenses are like a fence with vertical slats. They only let the vertical waves through. If you take two pairs of polarized glasses and turn one 90 degrees, the "pics" you see through them go pitch black. You've effectively blocked the transverse motion.

String Instruments: When a violinist bows a string, they aren't just pulling it. They are creating a standing transverse wave. If you use a strobe light on a bass string, you can visually freeze the "nodes" where the string isn't moving at all. It’s trippy.

Common Misconceptions in Visual Media

One of the biggest gripes physics teachers have with common pics of transverse waves is the lack of scale. You’ll see a wave with a massive amplitude (height) and a tiny wavelength. In reality, for something like a radio wave, the wavelength could be the size of a football field, while the amplitude is microscopic in terms of physical displacement.

✨ Don't miss: Scheduling an Appointment With Apple Care: How to Actually Get Help Without the Headache

Then there’s the "frozen" problem. A wave is a process, not an object. When you look at a still image, you lose the velocity component ($v = f \lambda$). You’re seeing a snapshot of energy transfer, not a thing that exists permanently in that shape.

How to Capture Better Wave Imagery

If you're a student or a creator trying to document these, stop using 2D silhouettes. Use 3D simulations that show particle displacement. If you are taking photos of actual physical waves—like a rope or a string—use a high shutter speed (at least 1/1000th of a second) to eliminate the motion blur that usually hides the actual wave geometry.

Interestingly, the most "accurate" pics of these waves often come from ripple tanks in university labs. They use overhead projectors to cast shadows of the wave crests onto a screen. This creates a high-contrast map of constructive and destructive interference. It’s where the math finally meets the eye.

Actionable Insights for Visualizing Physics

To truly understand what you're looking at when you see these images, you should change how you analyze them:

- Check the Axis: Always look at what the vertical axis represents. In a mechanical wave, it's physical distance (meters). In an electromagnetic wave, it’s field strength (Volts per meter). They look the same on paper, but they are fundamentally different realities.

- Identify the Medium: If the picture shows a wave in a vacuum, it’s light. If it shows a wave in a solid, it’s likely an S-wave or a mechanical vibration.

- Look for Interference: Real waves don't exist in isolation. Look for "moiré patterns" in photos, which indicate two waves crossing paths.

- Verify the Source: Don't trust generic "science background" stock photos. They often show waves that are mathematically impossible, with crests that are sharper than physics allows.

- Observe Polarization: If you’re looking at images of light waves, remember that the direction of the "wiggle" matters. This is why your phone screen looks weird when you wear polarized shades at the wrong angle.

Understanding the visual language of physics means seeing past the simple squiggle. The next time you browse through pics of transverse waves, remember you're looking at a map of energy, not just a curvy line. Focus on the displacement of the individual particles—or the oscillation of the invisible fields—and the whole concept starts to make a lot more sense.