You remember the "fried egg." That’s the classic image most of us have in our heads when we think about what’s going on inside our own bodies. A big purple circle in the middle, some wavy lines around it, and maybe a few jellybean-looking things scattered in the goo. But honestly? If you look at actual pics of an animal cell taken with an electron microscope, it looks less like breakfast and more like a crowded, chaotic alien cityscape. It’s messy. It’s packed. And it’s constantly vibrating with a level of activity that a 2D drawing just can’t capture.

Microscopy has come a long way since Robert Hooke looked at a piece of cork and thought it looked like a monk’s "cella." Today, we aren't just looking at blobs. We’re seeing individual protein motors walking along literal highways.

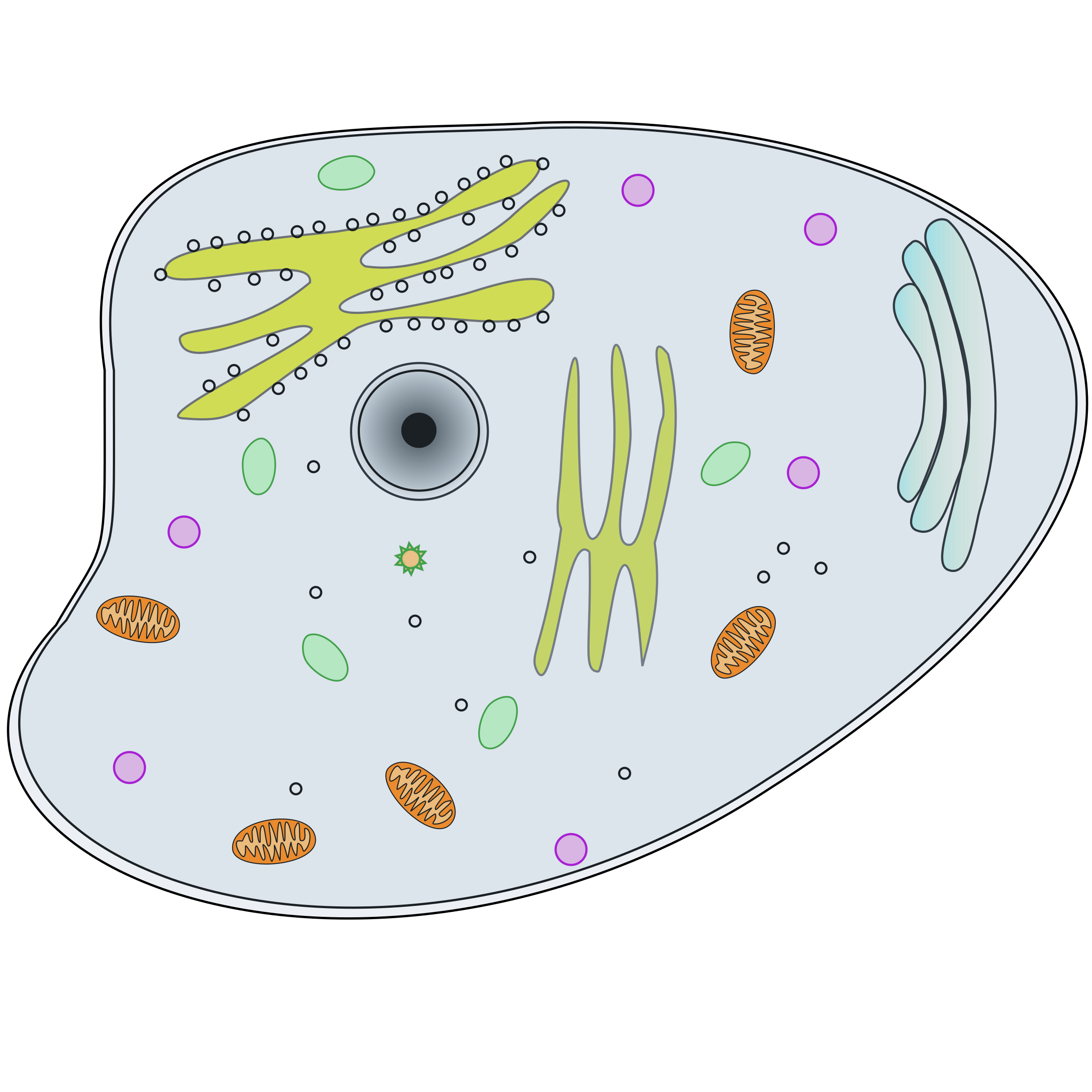

The Problem With "Standard" Animal Cell Images

Most diagrams are liars. They’re helpful liars, sure, but liars nonetheless. They show a lot of empty space between the nucleus and the outer membrane. In reality, the cytoplasm is a crowded "molecular soup." Imagine a crowded subway car at rush hour, then stuff it with more people, and then fill the remaining air with bouncy balls. That is the density we’re talking about.

When you browse through pics of an animal cell, specifically those using Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM), you see that organelles aren't just floating. They’re tethered. They’re squeezed. There is almost no "empty" water. Proteins are so tightly packed that they’re constantly bumping into each other, which is actually how many chemical reactions are forced to happen. If things weren't this crowded, life would be too slow to function.

It’s Not All Circles and Ovals

We’ve been conditioned to think cells are round. They aren't. Well, some are, like red blood cells or certain immune cells floating in your plasma. But most animal cells are shaped by what they do. A neuron looks like a cracked electrical wire stretching across a room. A muscle cell is a long, fibrous rope. An intestinal cell has tiny finger-like projections called microvilli that look like a shag carpet under a microscope.

When scientists take pics of an animal cell in its native tissue, they see these structures interlocking like a complex 3D puzzle. The "round" cell is mostly a byproduct of putting cells in a petri dish where they don't have neighbors to lean on, so they just bead up like a drop of oil.

🔗 Read more: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

The Nucleus: More Than Just a Brain

If you look at high-resolution images of the nucleus, you’ll notice it’s not a solid ball. It’s covered in "nuclear pores." These look like tiny donuts embedded in the surface.

These pores are the bouncers of the cell. They decide what gets in and out. In a typical 2D diagram, you see the DNA just sitting there like a pile of spaghetti. But in real-life imaging, we see that the DNA is organized into "territories." Certain genes are pushed to the edges when they need to be turned off, and pulled to the center when the cell needs to read them. It’s a physical filing system.

The Mitochondria: The Shapeshifters

We call it the powerhouse. Everyone knows that. But if you look at time-lapse pics of an animal cell (specifically using fluorescent tagging), you’ll see that mitochondria don't look like static beans. They are constantly fusing together into long networks and then snapping apart. This is called fission and fusion.

They move. They crawl toward parts of the cell that need energy. If a specific part of a muscle cell is working hard, the mitochondria will migrate there like a mobile power grid. Seeing this in motion changes how you think about "anatomy." It’s not a blueprint; it’s a dance.

Why Color is Usually "Fake"

Here is a bit of a reality check: most of those vibrant, neon pics of an animal cell you see on Instagram or in science journals are "false color."

💡 You might also like: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

Cells are basically translucent. Light passes right through them. To see anything, scientists have to use stains or fluorescent dyes.

- DAPI is a common dye that makes the nucleus glow bright blue.

- GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) can be attached to specific proteins to make them glow green.

So, when you see a stunning image of a cell with glowing red skeletons and green centers, you're looking at a map, not a photograph. The colors are added by the researcher to highlight specific parts. It’s like a thermal camera showing heat—it’s real data, but it’s not what your naked eye would see.

Seeing the "Skeleton"

One of the most mind-blowing things discovered in the last few decades is the cytoskeleton. For a long time, we thought cells were just bags of liquid. Then we got better microscopes.

The cytoskeleton is a scaffolding made of microtubules and filaments. It gives the cell its shape. But it also acts as a railroad system. There are motor proteins called kinesin that actually "walk" along these tubes, carrying bags of chemicals (vesicles) to different parts of the cell. There are amazing videos of this—it looks uncannily like a person walking with a giant backpack.

The Golgi Apparatus: The Cell’s Post Office

In pics of an animal cell, the Golgi looks like a stack of deflated pancakes. It’s where proteins get their "shipping labels" (usually sugar molecules) added to them so the cell knows where to send them. If the Golgi is damaged, the cell essentially loses its logistics network, and proteins end up in the wrong place, which is a major factor in various neurodegenerative diseases.

📖 Related: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

Different Views for Different Goals

Depending on what a scientist wants to see, they use different "cameras":

- Light Microscopy: Good for seeing live cells moving, but blurry.

- Confocal Microscopy: Uses lasers to take "slices" of a cell and reconstruct it in 3D.

- SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy): Gives you that amazing 3D surface detail. It makes a cell look like a planet.

- TEM (Transmission Electron Microscopy): This is how we see the "insides" in extreme detail, but the sample has to be sliced incredibly thin.

How to Look at Cell Images Like a Pro

When you're browsing pics of an animal cell, stop looking for the "perfect" textbook version. Look for the weirdness. Look for the way the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) wraps around the nucleus like a heavy blanket. Look for the tiny vesicles budding off the membrane—that’s the cell "eating" or "breathing."

Realize that what you’re seeing is a snapshot of a billion-year-old engineering marvel. Every line, every dot, and every fold has a specific physical purpose.

Actionable Insights for Students and Creators

If you are looking for pics of an animal cell for a project or just out of curiosity, keep these tips in mind to ensure you're getting the best information:

- Check the Scale Bar: Always look for a small line in the corner of the image (usually in micrometers or nanometers). Without it, you have no idea if you're looking at a whole cell or just a tiny fragment of a membrane.

- Identify the Technique: If the background is black and things are glowing, it’s fluorescence. If it looks like a gray, 3D sculpture, it’s SEM. Knowing the tool tells you what the image is actually trying to prove.

- Search for Specificity: Instead of "animal cell," search for "HeLa cell" or "CHO cell." These are specific cell lines used in labs globally. You'll get much higher quality, more accurate imagery.

- Use Databases: Don't just use Google Images. Go to the Cell Image Library or The Human Protein Atlas. These are gold mines for high-resolution, peer-reviewed cellular photography.

- Look for Artifacts: Sometimes, "blobs" in an image are just clumps of dye or damage from the slide-making process. Experts learn to ignore the "noise" to find the "signal."

Understanding the visual language of biology makes the world feel a lot bigger, even when you're looking at things that are microscopic. Next time you see a cell image, remember you aren't looking at a diagram; you're looking at a living city.