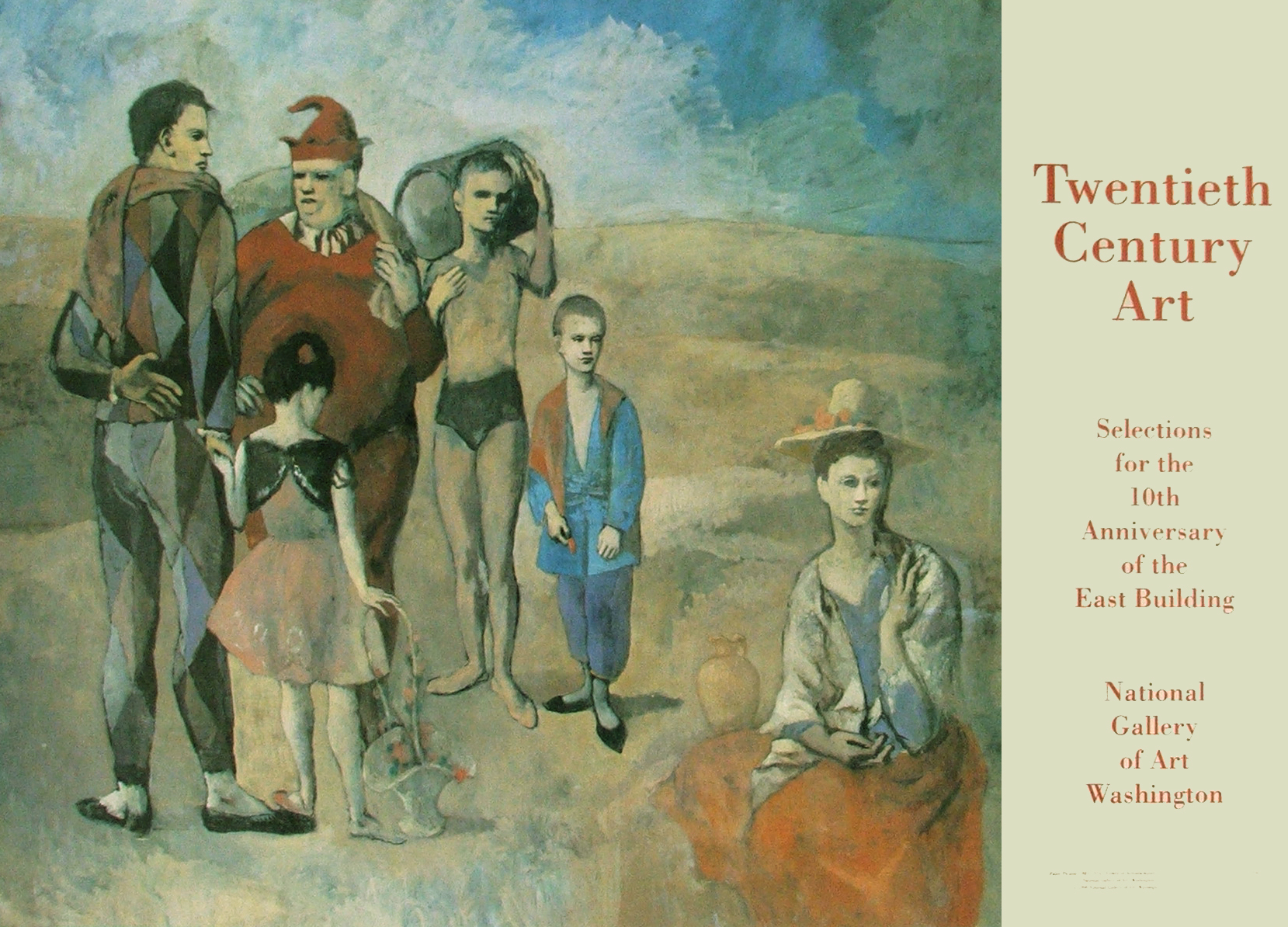

You walk into the National Gallery of Art in D.C., and it hits you. It’s huge. We're talking seven by seven and a half feet of canvas that basically anchors the entire East Building. Picasso's Family of Saltimbanques isn't just a painting; it’s a vibe shift in art history. It marks the moment Pablo stopped being a depressed kid painting blue rooms and started becoming the giant we know today.

Most people see a circus troupe. They see some colorful outfits and a desolate landscape. But honestly? This is one of the loneliest paintings ever made. It’s weirdly quiet for a group of performers.

The Rose Period Pivot

Before this, Picasso was stuck in the Blue Period. Everything was cold, miserable, and—literally—blue. He was mourning a friend’s suicide. Then he moved into the Bateau-Lavoir in Montmartre. He started hanging out at the Cirque Médrano. He saw these saltimbanques—it’s just a fancy French word for itinerant circus performers—and something clicked.

The palette warmed up. He started using these dusty pinks, terracottas, and muted oranges. This was the Rose Period. But don't let the "rose" thing fool you into thinking he was suddenly happy. These performers weren't the glamorous stars of a Vegas show. They were outcasts. They lived on the fringes. Picasso felt a kinship with them because, at the time, he was a struggling immigrant in Paris who could barely afford coal for his heater.

Who are these people, anyway?

Let’s look at the lineup. On the far left, you’ve got the massive figure of Harlequin. That’s Picasso. He painted himself into the work, which he did all the time, but here he’s leading the pack. He’s holding the hand of a small girl. Then there’s a fat buffoon in red, a couple of younger acrobats, and a woman sitting off to the right by herself.

Here is the kicker: none of them are looking at each other.

They are standing in a cluster, physically close, yet mentally they are miles apart. They’re in a wasteland. There’s no circus tent. No audience. No cheering. It’s just a bunch of people who work together and live together but seem totally incapable of connecting. It’s a masterclass in psychological isolation. If you’ve ever been at a party where you didn't know anyone and just stared at your phone, you get the energy of the Family of Saltimbanques.

🔗 Read more: Dating for 5 Years: Why the Five-Year Itch is Real (and How to Fix It)

The Ghost Under the Paint

Art historians at the National Gallery did some X-ray and infrared magic on this canvas years ago. What they found is wild. Picasso didn't just paint this; he wrestled with it.

He kept changing it.

The painting we see today is built on top of several other versions. There are at least three major iterations underneath the surface. In one version, the figures were much more engaged with each other. In another, the background was totally different. You can actually see some of the "ghosts" of the previous versions—pentimenti—if you look closely at the outlines of the figures.

Why does this matter? Because it shows Picasso’s obsession. He wasn't just "doing a circus painting." He was trying to find a specific balance of weight and emptiness. He eventually settled on this sparse, desert-like background because it forced the viewer to focus on the figures' internal states rather than their surroundings.

Size does matter here

The sheer scale of the Family of Saltimbanques was a massive risk. Back in 1905, huge canvases were usually reserved for "important" subjects. Think kings, battles, or religious scenes.

Picasso took that "grand scale" and used it for a bunch of nomadic circus freaks.

💡 You might also like: Creative and Meaningful Will You Be My Maid of Honour Ideas That Actually Feel Personal

It was a statement. He was saying that the inner lives of these social outcasts were just as monumental as any historical event. It’s an early hint of his ego, sure, but also his revolutionary spirit. He was breaking the rules of what was considered "worthy" of big art.

The Woman in the Corner

Let’s talk about the woman sitting on the right. She’s wearing a Majorcan hat. She’s isolated from the main group by a significant amount of empty space. Some critics think she represents a specific person from Picasso's life, while others see her as a symbol of the audience—the "other" who watches but never truly joins the family.

What’s interesting is how she breaks the verticality of the rest of the painting. Everyone else is standing, creating these tall, thin pillars. She’s a horizontal anchor. She keeps the whole composition from floating away into the sky. Her presence is grounding, yet her gaze is completely detached. She isn't watching the acrobats; she’s looking at something we can’t see.

Why it still hits different in 2026

We live in a world where we’re "connected" all the time, right? Social media, constant pings, the whole bit. Yet, the feeling of being alone in a crowd is a modern epidemic.

That’s why this painting doesn't feel like a dusty museum piece.

It feels contemporary. It’s the visual representation of "lonely together." Picasso captured a specific type of modern anxiety before the 20th century even really got moving. The Family of Saltimbanques isn't about the circus; it’s about the human condition of being slightly out of step with the world around you.

📖 Related: Cracker Barrel Old Country Store Waldorf: What Most People Get Wrong About This Local Staple

The colors are soft, but the reality is harsh. These people are "saltimbanques" because they jump and dance for bread, but in their downtime, they are just tired humans. Picasso didn't paint them performing. He painted them in the "in-between" moments. The moments where the mask slips.

How to see it for yourself

If you want to actually experience this thing, you need to go to Washington, D.C. It’s part of the Chester Dale Collection. Dale was this powerhouse financier who basically bought up every major French painting he could find. When he died, he left the Family of Saltimbanques to the National Gallery, but with a strict "no loans" policy.

That means if you want to see it, you have to go to the National Gallery of Art. It doesn't travel. It doesn't go on "world tours." It stays in D.C.

Pro-tip for your visit:

Stand about fifteen feet back first. Take in the scale. Then, walk up close—as close as the guards will let you—and look at the texture. Notice how thin the paint is in some areas. In parts of the background, it’s almost like a wash. Picasso was working fast, moving through ideas, and you can feel that frantic energy in the brushwork even though the subject matter looks still.

Check the feet. Picasso’s saltimbanques often have feet that look slightly unfinished or blurry. It gives them a sense of being transitory, like they could pick up and leave the frame at any second.

Actionable Takeaways for Art Lovers

- Don't ignore the Rose Period. Everyone talks about Cubism or the Blue Period, but the Rose Period is where Picasso found his soul as a painter. Look for other works from 1904-1906 to see how he refined his use of color.

- Study the Pentimenti. If you’re an artist, look at the "mistakes" or changes in the Saltimbanques. It’s a reminder that even masters don't get it right on the first try. Process is everything.

- Visit the NGA East Building. While you’re there to see the Picasso, check out the surrounding rooms. The gallery curates the space to show the transition from post-impressionism into the radical shifts of the early 20th century.

- Read "The Saltimbanques" by Rainer Maria Rilke. The poet was so obsessed with this painting that he lived with it for a while (it was owned by a friend) and wrote the fifth of his Duino Elegies about it. Reading the poem while looking at the painting is a whole different level of experience.

The Family of Saltimbanques remains one of the most enigmatic pieces in American collections. It’s a bridge between the old world of representational art and the fragmented, psychological world of modernism. It’s beautiful, it’s weird, and it’s deeply human. Even after 120 years, we’re still trying to figure out what those performers are thinking about in that empty desert.