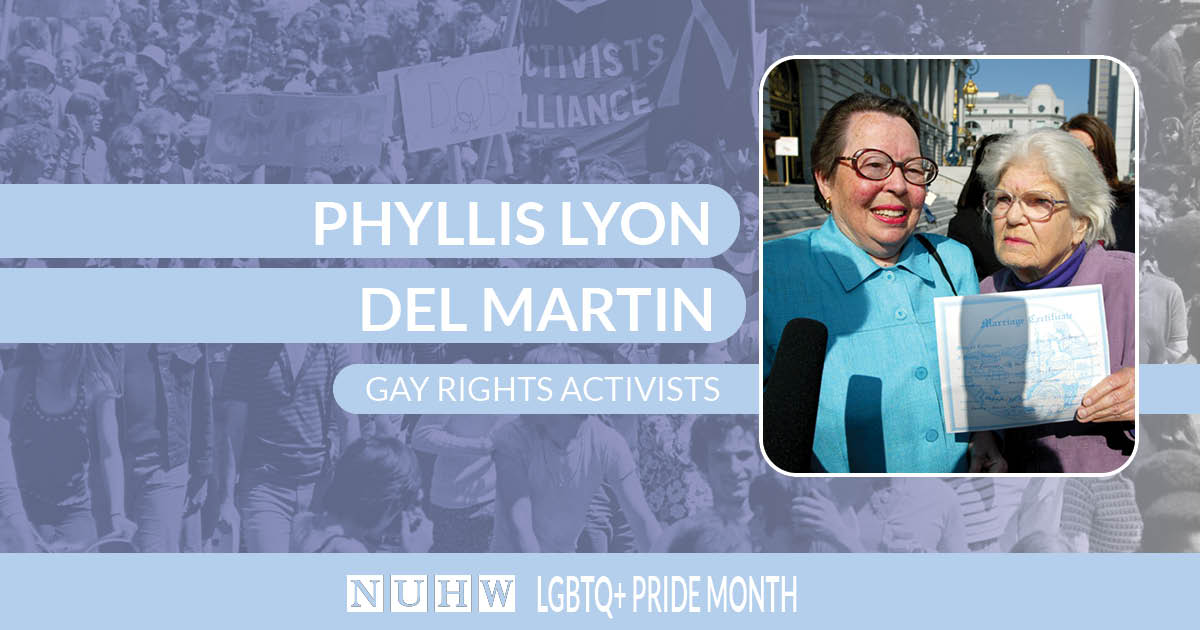

You’ve probably seen the photo. Two elderly women, glowing in pastel-colored suits—one in pink, one in blue—clutching each other’s hands while a young Gavin Newsom officiates their wedding. It’s an iconic image of 2008. But honestly, if you only know Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin for that one afternoon at San Francisco City Hall, you’re missing about 90% of the story.

They weren't just the "cute grandma" pioneers of marriage equality.

These were two journalists who started a secret society when being gay was literally a mental disorder according to the APA. They weren't just activists; they were outcasts who decided they were tired of hiding in the shadows of the 1950s.

The Secret Origins of the Daughters of Bilitis

Back in 1950, Seattle wasn't exactly a neon-lit haven for queer love. That’s where they met. Del Martin was a 29-year-old single mother and journalist. Phyllis Lyon was 25, also a journalist, and—by her own admission—pretty much straight at the time.

That changed. Fast.

By 1953, they had moved into a small apartment in San Francisco. They wanted a place to dance without looking over their shoulders for a police raid. Seriously. In the 50s, the "gay scene" was mostly bars that were constantly being shaken down by the cops. If your name ended up in the paper after a raid, you lost your job. Your family disowned you. Your life was basically over.

So, in 1955, they joined forces with three other couples to create the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB).

📖 Related: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

The name was a clever, nerdy ruse. It sounded like a social club or a poetry society, named after a fictional contemporary of Sappho. If a neighbor asked, "Hey, what’s that meeting about?" they could just say it was a women's literary group. It was the first nationwide lesbian organization in the U.S., and it started in a living room.

The Ladder: A Lifeline in Print

Because they were both writers, they knew that visibility—even if it was anonymous—mattered. They launched The Ladder in 1956. This wasn't some glossy magazine you’d find at a newsstand. It was a mimeographed newsletter sent in plain brown envelopes so the mailman wouldn’t know what was inside.

Imagine being a woman in a small town in the Midwest in 1958, thinking you’re the only person on earth who feels this way. Then, this little envelope arrives. It tells you that you aren't sick. It tells you there are others.

Phyllis was the editor. Del was the president. They were basically running a national underground railroad of information from their kitchen table.

Why Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin Didn't Stop at "Gay Rights"

One thing people get wrong is thinking they only cared about LGBTQ+ issues. They were intersectional before that was even a buzzword.

In the late 60s, they joined the National Organization for Women (NOW). They actually insisted on a "couple's rate" for membership, which was only offered to heterosexual married couples at the time. They were annoying, persistent, and absolutely right. Del eventually became the first openly lesbian woman elected to NOW’s national board.

👉 See also: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

But check this out: Del Martin also wrote Battered Wives in 1976.

It was one of the first books in the country to treat domestic violence as a systemic issue rather than a "private family matter." She wasn't just fighting for the right to love; she was fighting for the right to be safe in your own home.

Meanwhile, Phyllis was busy helping found the National Sex and Drug Forum and working with the Glide Memorial United Methodist Church to bridge the gap between religion and the "homosexual" community. They were busy. Very, very busy.

The Marriage That Happened Twice

By the time 2004 rolled around, Phyllis and Del had been together for over 50 years. They were the "gold standard" of relationships in San Francisco. So, when Mayor Gavin Newsom decided to challenge the law by issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, he knew exactly who had to be first.

Kate Kendell, then the head of the National Center for Lesbian Rights, called them up. She basically said, "We need you to do one more thing for the movement."

Phyllis, being Phyllis, reportedly laughed and asked Del if they had anything better to do that day.

✨ Don't miss: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

They didn't.

On February 12, 2004, they were the first couple married in what became known as the "Winter of Love." But the high didn't last. A few months later, the California Supreme Court voided all those marriages.

Most people would have been crushed. They just kept working.

They were plaintiffs in the lawsuit that eventually led the court to overturn the ban in 2008. On June 16, 2008, they got married again. This time, it was legal. This time, it stuck. Del died just two months later at the age of 87. She went out a legally married woman after 55 years of partnership.

Phyllis lived until 2020, passing away at 95. She spent her final years in the same Noe Valley house they bought together in 1955—the house that is now a designated San Francisco landmark.

How to Apply Their Legacy Today

Honestly, looking at the lives of Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin gives you a pretty clear blueprint for how to handle a world that feels like it’s sliding backward. They didn't have a massive budget or a PR firm. They had a typewriter and a kitchen table.

- Focus on the "Minority within the Minority": They realized that the "gay movement" was mostly led by men and the "feminist movement" was mostly led by straight women. They carved out a space specifically for lesbians because nobody else was doing it.

- Persistence is a literal superpower: They didn't win marriage equality in a decade. It took them fifty years. If you’re feeling burnt out after six months of activism, look at Del and Phyllis. They played the long game.

- Document everything: Without The Ladder, we’d have almost no record of what lesbian life was like in the 50s. If you’re doing something important, write it down. Record the stories.

The next time you see that photo of the two women in the pink and blue suits, remember they weren't just a sweet old couple. They were the architects of a revolution. They fought "the church, the couch, and the courts," and against all odds, they won.

If you want to support the preservation of this history, look into the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco. They currently house the archives of Lyon and Martin, including those famous wedding suits. You can also visit the Lyon-Martin House in Noe Valley, which serves as a physical reminder that change starts at home.