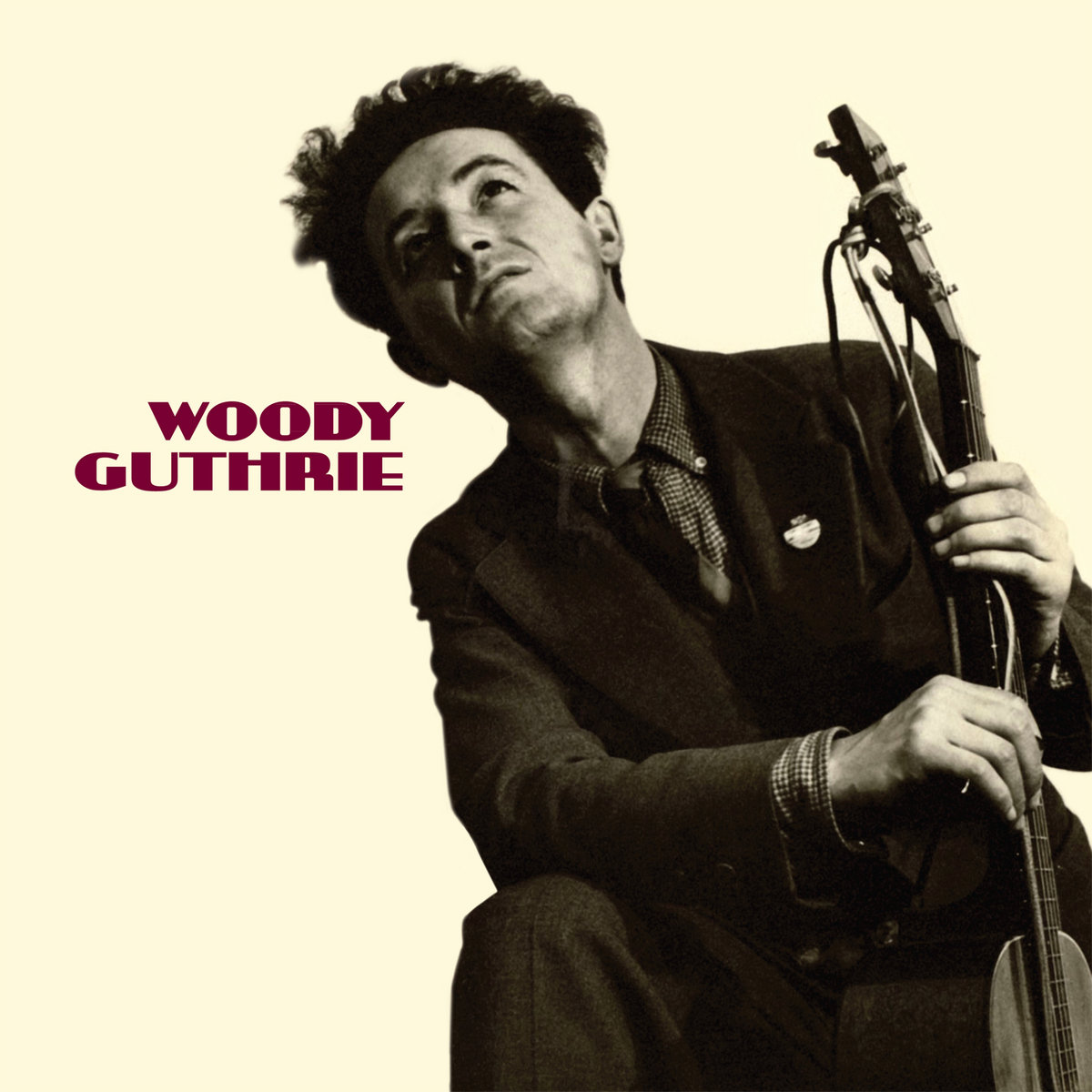

Ever looked at a photo and felt like you could hear the person breathing? That’s what happens when you stare at those grainy, black-and-white photos of Woody Guthrie. He wasn't just a guy with a guitar; he was a walking, singing piece of American history. You've probably seen the most famous one. He’s leaning back, hair a mess of wiry curls, holding a guitar that famously promises to kill fascists.

But there’s so much more to the visual record of Guthrie than just that one defiant pose.

Honestly, the story of how these images came to be is as rugged and rambling as the man himself. We aren't just talking about promotional headshots for a record label. These were moments captured in subway stations, on dusty porches, and in the cramped living rooms of the 1940s folk scene. If you want to understand the "Dust Bowl Troubadour," you have to look past the myths and actually see the man through the lens of the photographers who followed him.

The Man Behind the Machine: Al Aumuller’s Iconic 1943 Shots

Most of what we visualize when we think of Woody comes from a single afternoon in March 1943. Al Aumuller, a staff photographer for the New York World-Telegram, took a series of portraits that basically defined Guthrie’s public image forever.

It’s kind of wild. Aumuller wasn't trying to create an immortal folk icon. He was just doing his job, snapping a musician who had recently published his semi-autobiographical book, Bound for Glory.

In these photos, Woody is wearing his standard work clothes—rough shirts and a weather-beaten look that made him seem like he’d just stepped off a freight train. Which, let's be real, he often had. The most famous shot from this session shows the "This Machine Kills Fascists" sticker prominently displayed on his guitar. It wasn't just a prop. For Woody, the music was a weapon, and Aumuller captured that intensity perfectly.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

Why the Aumuller Portraits Stick

There is a specific raw quality to these prints. Woody isn't smiling for the camera. He looks slightly to the side, focused on something the viewer can't see. His hands are thick, capable, and clearly used to hard work.

You can find these original prints today in the Library of Congress. They’re part of the New York World-Telegram & Sun collection. If you ever get the chance to see a high-res digital scan, look at his eyes. There’s a mix of exhaustion and absolute certainty. It's the face of a man who had seen the worst of the Great Depression and still decided to write "This Land Is Your Land."

Eric Schaal and the "Ramblin' Around" New York Series

While Aumuller gave us the "studio" version of Woody, Eric Schaal gave us the man in motion. In 1943, on assignment for LIFE magazine, Schaal followed Guthrie through the streets of New York City.

These photos are arguably more intimate. They show Woody in his element:

- Singing on the stoops of brownstones to a crowd of neighborhood kids.

- Strumming his guitar in the middle of a crowded subway car.

- Hanging out in bars, looking totally at ease with the working-class people he sang about.

What’s sort of heartbreaking is that LIFE didn't actually run these photos at the time. They sat in the archives for decades. It wasn't until much later that people realized how precious they were. They show a version of New York that doesn't exist anymore—unpolished, loud, and full of character. Schaal caught Woody not as a "legend," but as a guy just trying to make a buck and share a song with whoever would listen.

🔗 Read more: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

The Lost Years: Phillip Buehler and the Greystone Photos

Most people like to remember the young, vibrant Woody. But the later photos of Woody Guthrie tell a much heavier story. By the late 1950s, Woody was suffering from Huntington’s disease, a brutal neurological disorder that was poorly understood at the time.

He spent years in hospitals, including Greystone Park State Hospital in New Jersey.

For a long time, this part of his life was a "black hole" in the public record. However, photographer Phillip Buehler did some incredible work uncovering this period. In his book Woody Guthrie’s Wardy Forty, Buehler combined historic family photos with his own shots of the now-decaying hospital rooms where Woody lived.

It’s grim stuff. But it’s necessary.

Seeing the contrast between the wiry, energetic man in the 1943 Aumuller photos and the frail, aging man in the later family snapshots is a punch to the gut. It reminds us that Woody was human. He wasn't just a symbol on a t-shirt. He was a father and a husband who spent his final years in a "spooky" institution, visited by a young, star-struck Bob Dylan.

💡 You might also like: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

How to Find Authentic Woody Guthrie Images

If you're looking for high-quality, historically accurate images, don't just rely on a random Google Image search. You’ll run into a lot of AI-upscaled junk or misattributed photos.

Instead, check out these real repositories:

- The Library of Congress (LOC): This is the gold standard. They hold the Aumuller collection. You can search their "Prints and Photographs Online Catalog" and often download high-resolution TIFF files for free.

- The Woody Guthrie Center (Tulsa, Oklahoma): This place is the mecca for Guthrie fans. They have the actual archives, including personal family scrapbooks that were digitized by the Northeast Document Conservation Center.

- Smithsonian Folkways: They often have rare promotional shots and candid images used for his album covers and liner notes.

- The Alan Lomax Collection: Lomax was the guy who first recorded Woody for the Library of Congress in 1940. His collection includes snapshots of Woody during those early sessions in Washington, D.C.

The Visual Legacy of a "Hoping Machine"

Woody once wrote that a human being is basically just a "hoping machine." You see that hope in every single frame of his film history. Even when he’s looking ragged, there’s a spark.

Photographers like Sid Grossman and Arthur Rothstein also captured the era Woody lived through—the migrant camps, the dust storms, the bread lines. Even if Woody isn't in every one of those photos, he’s there in spirit. His music and his image are inseparable from the visual history of the American worker.

Actionable Steps for the Guthrie Enthusiast:

- Verify the Photographer: If you find a photo you love, look for the credit. Is it Al Aumuller? Eric Schaal? Knowing the photographer gives you the context of why the photo was taken (e.g., a book promo vs. a candid street scene).

- Visit the Archives Online: Don't just settle for low-res thumbnails. Use the Library of Congress's digital ID system (like

LC-DIG-ppmsca-74705) to find the highest-quality version of the "This Machine Kills Fascists" portrait. - Support the Preservation: The Woody Guthrie Archives in Tulsa constantly works to restore old film and paper. If you’re a fan, check out their exhibits—they often rotate through rare physical prints that you can’t see anywhere else.

- Look for the Scrapbooks: Woody was a prolific scrapbooker. The digitized versions of these books at the Woody Guthrie Center contain "identified people and places that were previously unknown," offering a much more personal look at his life than any professional portrait ever could.