You’ve probably seen the "official" ones. Those super-crisp, perfectly lit photos of the space station floating against the deep black of the vacuum, looking like a high-end plastic model. They’re beautiful. They’re also kinda clinical.

What's actually wild is that the best photos of the space station aren't usually the ones NASA puts on posters. They’re the blurry, heat-shimmered shots taken by guys in their backyards in suburban Ohio, or the messy, cluttered interior shots where you can see a floating Velcro strip and a half-eaten bag of dried apricots. Space is messy. The International Space Station (ISS) is essentially a giant, flying laboratory held together by 25 years of international cooperation and a whole lot of high-grade tape.

If you want to understand what's really happening 250 miles above our heads, you have to look past the PR shots.

The Secret World of Earth-Bound ISS Photography

Most people assume you need a billion-dollar satellite to get a good look at the ISS. You don't. Honestly, some of the most mind-blowing imagery comes from amateur "astrophotographers" like Thierry Legault or Andrew McCarthy.

These guys use specialized telescopes and high-speed cameras to catch the station as it transits the sun or the moon. It happens in a blink. Seriously, the ISS moves at about 17,500 miles per hour. If you're looking through a telescope, the station crosses the face of the moon in less than half a second. To capture that, you aren't just taking a photo; you're basically conducting a ballistic intercept mission with a camera lens.

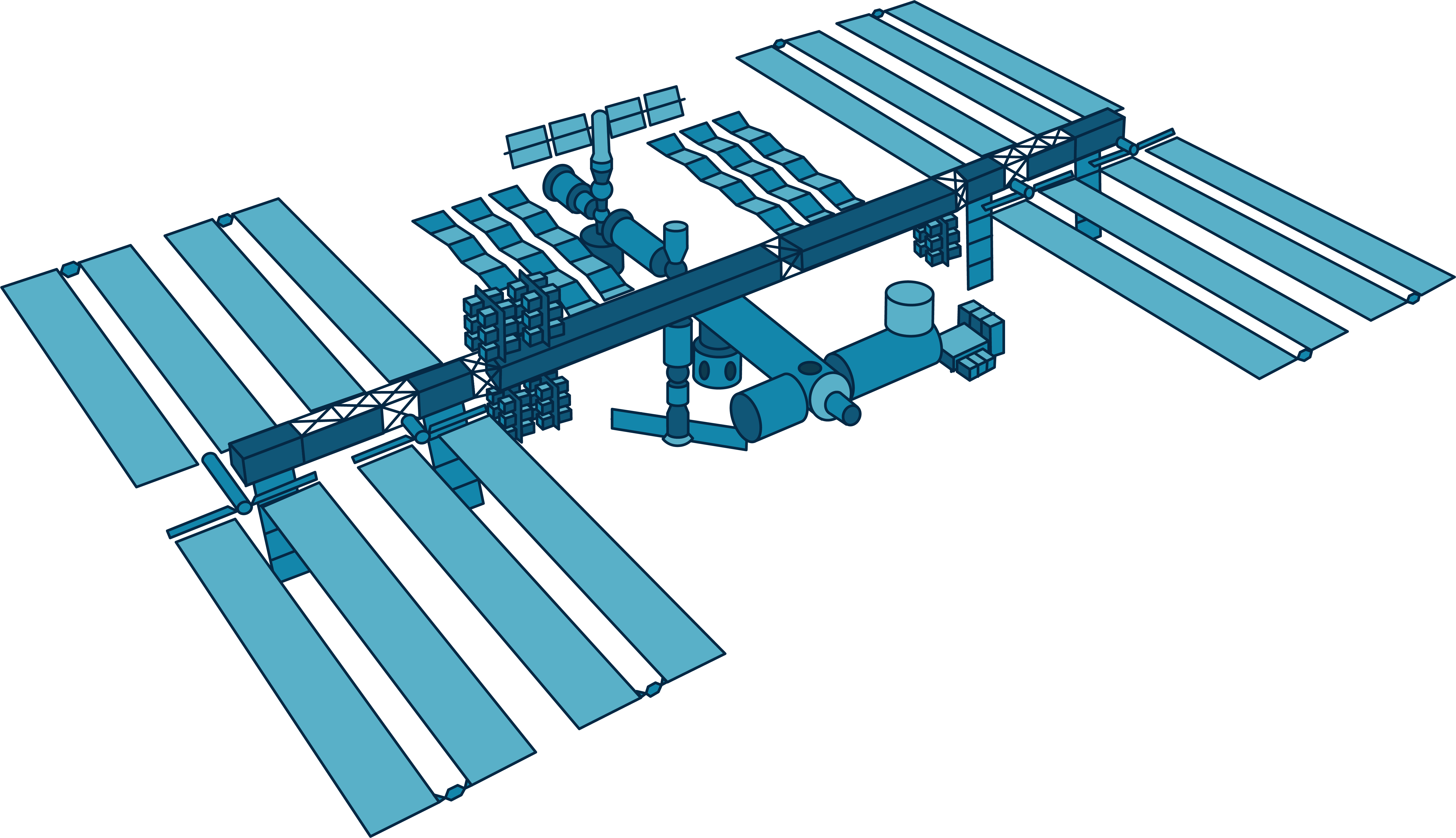

When you see these photos, you notice things the official NASA archives don't always emphasize. You see the massive solar arrays—spanning 240 feet—glowing with a strange, bronze hue. You can see the individual modules like Destiny and Zvezda. Sometimes, if the lighting is just right and the photographer is lucky, you can even see a docked Dragon or Soyuz capsule. It makes the station feel real. Not just a dot in the sky, but a massive machine where people are currently brushing their teeth and doing science.

Why the Cupola Changed Everything

Before 2010, photos from the space station were mostly taken through small, thick, scratch-prone portholes. Then came the Cupola. It’s that seven-windowed observatory module that looks like something straight out of Star Wars.

It changed the game.

Astronauts like Chris Hadfield and Scott Kelly became household names because of the Cupola. They could finally see the "big picture." They weren't just looking at the horizon; they were looking straight down at the eye of a hurricane or the neon veins of Tokyo at night. The Cupola allowed for wide-angle photos of the space station interior that included the Earth as a backdrop. This created a sense of scale that was previously impossible to convey.

📖 Related: Who is Blue Origin and Why Should You Care About Bezos's Space Dream?

However, taking photos from the ISS is a technical nightmare. Think about it. You're in a tin can moving five miles per second. The Earth below is moving. You're moving. And the light? The light is brutal. Every 90 minutes, the station goes through a full day-night cycle. You have about 45 minutes of blinding, unfiltered sunlight followed by 45 minutes of total pitch black.

Dealing with the "Space Glow"

There is a phenomenon called "airglow." In long-exposure photos of the space station, you’ll often see a thin, ghostly green or gold line hugging the curve of the Earth. It’s not a camera glitch. It’s the atmosphere itself glowing because of atoms being energized by solar radiation.

Astronauts have to use specialized mounts to keep their cameras steady against the vibration of the station's life support systems. If you don't, every city light becomes a shaky squiggle. They use high-end Nikon and Sony bodies—usually unmodified off-the-shelf gear—but with heavy-duty thermal protection.

The Raw Reality of the Interior Shots

If you want to see the "real" ISS, look at the photos of the Zvezda module. It’s the Russian heart of the station. Unlike the sterile, white, "Apple Store" vibe of the American modules, Zvezda is loud. It’s covered in wires. There are photos of icons of saints, pictures of Yuri Gagarin, and fans everywhere to keep the air moving so the astronauts don't suffocate in a bubble of their own exhaled carbon dioxide.

These interior photos of the space station tell a story of long-term habitation. You see the wear and tear. You see where the paint is chipped. You see the "stuff."

- Cables snaking across handrails.

- Ziploc bags of coffee taped to walls.

- Laptops hovering mid-air, tethered by a single cord.

- The "Space Toilet" (which is way less glamorous than it sounds).

The ISS isn't a luxury hotel. It's a 450-ton science experiment that has been continuously inhabited since November 2000. That’s over two decades of human grime and ingenuity captured in pixels.

How to Spot a Fake (or "Enhanced") Photo

We live in the era of AI and heavy Photoshop. A lot of the "most viral" photos of the space station are actually composites or straight-up CGI.

If you see a photo where the ISS is positioned perfectly in front of a giant, glowing nebula that looks like a technicolor dream, it’s fake. Nebulas aren't visible like that to the naked eye or even to standard cameras in a single shot. Another giveaway is the stars. In real photos of the station, the stars often look faint or non-existent. Why? Because the station is so bright (it’s made of polished metal and white thermal blankets) that the camera has to use a fast shutter speed. If you expose for the stars, the ISS becomes a blown-out white blob.

👉 See also: The Dogger Bank Wind Farm Is Huge—Here Is What You Actually Need To Know

Real space photography is often "noisy." High-energy cosmic rays hit the camera sensors, creating little white or colored speckles called "hot pixels." NASA spends a lot of time cleaning these up, but if you look at the raw files, they’re everywhere. It’s a constant reminder that the environment up there is actually quite hostile to electronics—and us.

The Future: Commercial Stations and New Views

The ISS won't be around forever. We’re looking at a deorbit date somewhere around 2030. That means the library of photos of the space station we’re building now is a finite historical record.

Upcoming commercial stations like Axiom or Blue Origin’s "Orbital Reef" are being designed with photography in mind. They’re planning larger windows and better lighting. We are moving from the "pioneer" era of space photography to the "cinematic" era. But there is something raw about the current ISS photos that we might lose. The ISS looks like a "ship" in the traditional sense—clunky, evolving, and utilitarian.

Why You Should Care About the "Bad" Photos

Sometimes, the most important photos are the ones that look terrible. In 2021, when a Russian module (Nauka) accidentally fired its thrusters and tilted the station, the photos taken during the recovery weren't "pretty." They were frantic. They showed the stress on the docking adapters and the odd angles of the solar arrays.

Those photos are evidence of survival.

They remind us that the ISS is a fragile bubble. Every photo of a scratch on a window or a dent in a micrometeoroid shield is a data point for engineers. These images are used to track the health of the hull. In a very literal way, photography keeps the crew alive.

Setting Up Your Own "ISS Spotting" Rig

If you're reading this and thinking, "I want my own photos of the space station," you can actually do it. You don't need a NASA budget.

First, get an app like "ISS Detector" or use the NASA "Spot the Station" website. It'll tell you exactly when the station is flying over your house. To the naked eye, it looks like a very bright, steady white light moving faster than an airplane. It doesn't blink.

✨ Don't miss: How to Convert Kilograms to Milligrams Without Making a Mess of the Math

For photography:

- Use a tripod. This isn't optional.

- Go Wide. Use a wide-angle lens (14mm to 24mm) to capture the long "streak" of the station across the sky.

- Long Exposure. Set your shutter to 10-30 seconds. You’ll get a beautiful white arc cutting through the stars.

- High ISO. Somewhere between 800 and 3200 depending on your light pollution.

If you want the "close-up" shots where you can see the solar panels, you’ll need a telescope with a "tracking" mount. This is the hard part. The ISS moves so fast that most standard star-trackers can't keep up. You have to manually "nudge" the telescope or use specialized software like OpticTracker.

The Ethical Side of Space Imagery

There's a weird debate in the community about "beautifying" space. Should we color-correct photos of the space station to make them look more like what we see in movies?

Some purists say no. They argue that by making space look "pretty" and "easy," we lose the sense of how difficult and dangerous it actually is. Others argue that if a photo of the ISS inspires a kid to study physics, it doesn't matter if the saturation was turned up a bit.

Regardless of where you stand, the sheer volume of imagery coming off the station is unprecedented. We are the first generation of humans who can check Twitter and see a photo of our hometown taken from space just twenty minutes ago. That’s a massive psychological shift. It turns the "final frontier" into a neighborhood.

Practical Steps for Enthusiasts

If you’re serious about diving deeper into this world, stop looking at Google Images and go to the source. The Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth is a massive, searchable database of every photo ever taken by an astronaut. It’s a bit clunky, but it’s the raw, unedited truth.

- Search by location: Find photos of your own city from the ISS.

- Check the metadata: Look at the lens and camera settings used. Most astronauts use a Nikon D5 or D6 with a 400mm or 800mm lens for ground shots.

- Follow the crew: Astronauts on the current Expedition (like those from the Crew-7 or Crew-8 missions) often post "behind the scenes" photos on social media that never make it to the official NASA Flickr.

Don't just look at the station; look at what the station is looking at. The imagery of the ISS isn't just about a machine in orbit. It's about a perspective change. When you see a photo of the space station silhouetted against the thin blue line of our atmosphere, the political borders on the ground disappear. You just see a very small, very beautiful, and very lonely planet.

Start tracking the passes. Grab a camera. Even a basic smartphone with a "night mode" can catch the ISS streak if you're steady enough. It’s the easiest way to feel connected to the people living and working in the sky. Once you start seeing the station as a real place—a place with messy desks and scratched windows—the "official" photos start to feel a lot more meaningful.