Checking your own back is basically impossible without a hand mirror or a very patient partner. Most of us just don't look there. But because the back is a huge expanse of skin that often gets "accidentally" toasted during summer trips or outdoor work, it’s a prime spot for trouble. When people search for photos of skin cancer on back, they usually want a "yes" or "no" answer to a spot they just noticed. Honestly? It's never that simple.

Skin cancer doesn't follow a perfect rulebook. One person’s melanoma looks like a tiny, harmless freckle, while another person’s basal cell carcinoma looks like a patch of dry skin that just won’t quit. You’ve probably heard of the ABCDEs of melanoma, but on the back, things get weird. The skin is thicker there. Constant friction from clothes can make a lesion look irritated or bloody when it’s actually something else—or vice versa.

What do these spots actually look like?

If you scroll through medical databases like the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) or VisualDx, you’ll see a massive range of imagery. Some photos of skin cancer on back show what doctors call "The Ugly Duckling." This isn't a technical medical term in the way "histopathology" is, but it’s a legitimate diagnostic tool. Basically, if you have thirty moles on your back and they all look like little brown dots, but one is a jagged black smudge, that’s the one to worry about.

Melanoma is the big one. It’s the one that kills. On the back, it often presents as a large, multi-colored lesion. You might see shades of midnight blue, charcoal, or even a weird ghostly white where the body is trying to "eat" the cancer back. But then there’s Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC). This is the most common type. In photos, BCC on the back often looks like a "pearly" bump. It might have tiny blood vessels—called telangiectasia—branching across it like a tiny road map. It’s subtle. You might think it’s just a pimple that won’t heal.

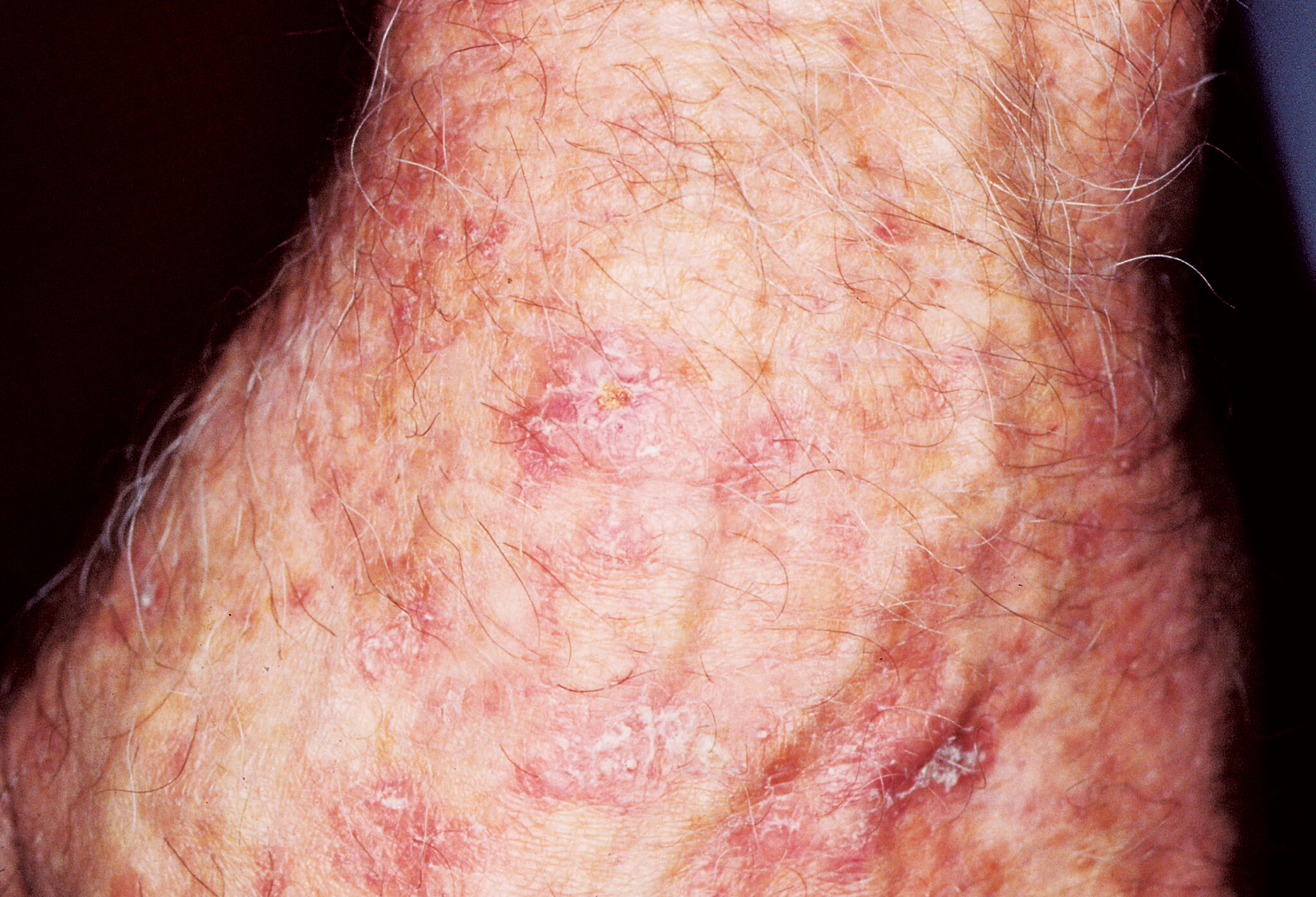

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) is different again. It’s often scaly. If you find a photo of SCC on a back, it usually looks like a crusty, red patch. It might feel rough, like sandpaper. People often mistake this for eczema or a bit of psoriasis. The difference? Eczema usually responds to moisturizer. Cancer doesn't.

✨ Don't miss: Why Meditation for Emotional Numbness is Harder (and Better) Than You Think

Why the back is a "blind spot" for survival

There is a terrifying statistic often cited by oncologists: melanomas on the back have a higher mortality rate than those on the legs or arms. It’s not because the cancer is "stronger." It’s because by the time someone sees it, it’s already deep.

Think about it. You see your face in the mirror every morning. You see your arms while you're typing or eating. But your back? You might go months without really inspecting the area between your shoulder blades. According to a study published in JAMA Dermatology, men are particularly prone to late-stage melanoma on their backs because they are less likely to perform regular skin checks or use sunscreen consistently during outdoor activities.

Identifying the "Normal" vs. "Not Normal"

It is incredibly easy to freak yourself out looking at photos of skin cancer on back online. You’ll see a photo of a Seborrheic Keratosis (SK) and think it’s a melanoma. SKs are totally benign. They look like "stuck-on" warts—almost like someone pressed a piece of brown candle wax onto your skin. They are extremely common as we age.

But here is where it gets nuanced. You can have an SK and a melanoma right next to each other.

🔗 Read more: Images of Grief and Loss: Why We Look When It Hurts

- Symmetry: If you drew a line through a normal mole, the halves should match. Cancerous growths are usually "off-kilter."

- The Border: Is it blurry? Does it look like ink leaking into a paper towel? That’s a red flag.

- Color: Uniformity is good. If you see a "patriotic" mole (red, white, and blue) or just a mix of tans and blacks, it needs a professional look.

- Diameter: The old rule was "larger than a pencil eraser." However, dermatologists now catch "micro-melanomas" that are smaller than a grain of rice.

- Evolution: This is the most important one. Has it changed in the last three months? If it’s growing, itching, or bleeding, stop Googling and call a doctor.

The role of professional photography in diagnosis

In 2026, we aren't just relying on a doctor's naked eye. Dermatologists use something called a dermatoscope. It’s a handheld tool that uses polarized light to look into the skin, not just at it. When you look at professional photos of skin cancer on back taken through a dermatoscope, you see structures like "pigment networks" and "blue-white veils."

These are patterns the human eye literally cannot see without help. This is why a "clear" photo you take on your smartphone might not be enough for a doctor to give you a definitive "you're fine" over an app. The resolution of the skin's deeper layers is where the truth lives.

Real-world examples of "The Great Mimickers"

I’ve seen cases where what looked like a simple "back acne" scar turned out to be Amelanotic Melanoma. This is a version of skin cancer that has no pigment. It’s pink. It looks like a scar or a harmless bump. This is why "photos" are only one piece of the puzzle. You have to feel the skin. Is it firm? Does it feel like a pebble under the surface?

Another common mix-up is a Cherry Angioma. These are bright red, circular spots. They look like a drop of red ink. They are almost always harmless, but because they look "weird" and show up suddenly, people panic. If you see a photo of a bright, cherry-red, perfectly round spot, it’s likely an angioma, not cancer. But again, "likely" isn't "definitely."

💡 You might also like: Why the Ginger and Lemon Shot Actually Works (And Why It Might Not)

What you should do right now

If you’ve been looking at photos of skin cancer on back because you found something suspicious, here is the reality: a photo cannot biopsy a lesion. You can’t "self-diagnose" your way out of the anxiety.

First, get someone to take a high-resolution photo of the spot. Use a coin (like a dime) next to the spot for scale. Use natural light, but not direct, blinding sunlight. Take a "bird's eye view" shot from a few inches away, and then a wider shot to show where it is on your body.

Next, check your history. Did you have blistering sunbursts as a kid? If you grew up in the 80s or 90s without the modern obsession with SPF 50, your risk profile is higher. The damage done thirty years ago is what shows up on your back today.

Actionable steps for your skin health

- The Partner Check: Once a month, have someone look at your back. Tell them to look for the "Ugly Duckling." Don't just look for "scary" things; look for things that are different from your other spots.

- The Baseline Photo: Take a photo of your entire back once a year. Store it in a secure folder. If a spot appears next year, you can check the "archive" to see if it was there before.

- Professional Skin Mapping: If you have more than 50 moles, or a family history of skin cancer, look into "Total Body Photography." This is a medical service where they use high-tech cameras to map every inch of your skin. It takes the guesswork out of the "is that new?" question.

- Don't ignore the itch: Skin cancer isn't always painful. Often, it’s just "persistent." If you have a spot on your back that itches for three weeks straight and it’s not a bug bite, get it checked.

- The "Rule of Three": If a spot has three or more colors, three or more different border shapes, or has grown by 3mm, it’s an automatic doctor visit.

Seeing photos of skin cancer on back can be a wake-up call. It’s easy to ignore what we can't see, but the skin on your back is just as vulnerable as your face. Prevention is great, but early detection is the only thing that actually saves lives once the damage is done. Use the photos as a guide, but use a dermatologist for the answer.

Key Takeaway: Digital images are a starting point for awareness, but they lack the depth and textural information required for a medical diagnosis. The back is a high-risk area specifically due to the "visibility gap," making regular, documented inspections and professional screenings non-negotiable for those with significant sun exposure history.