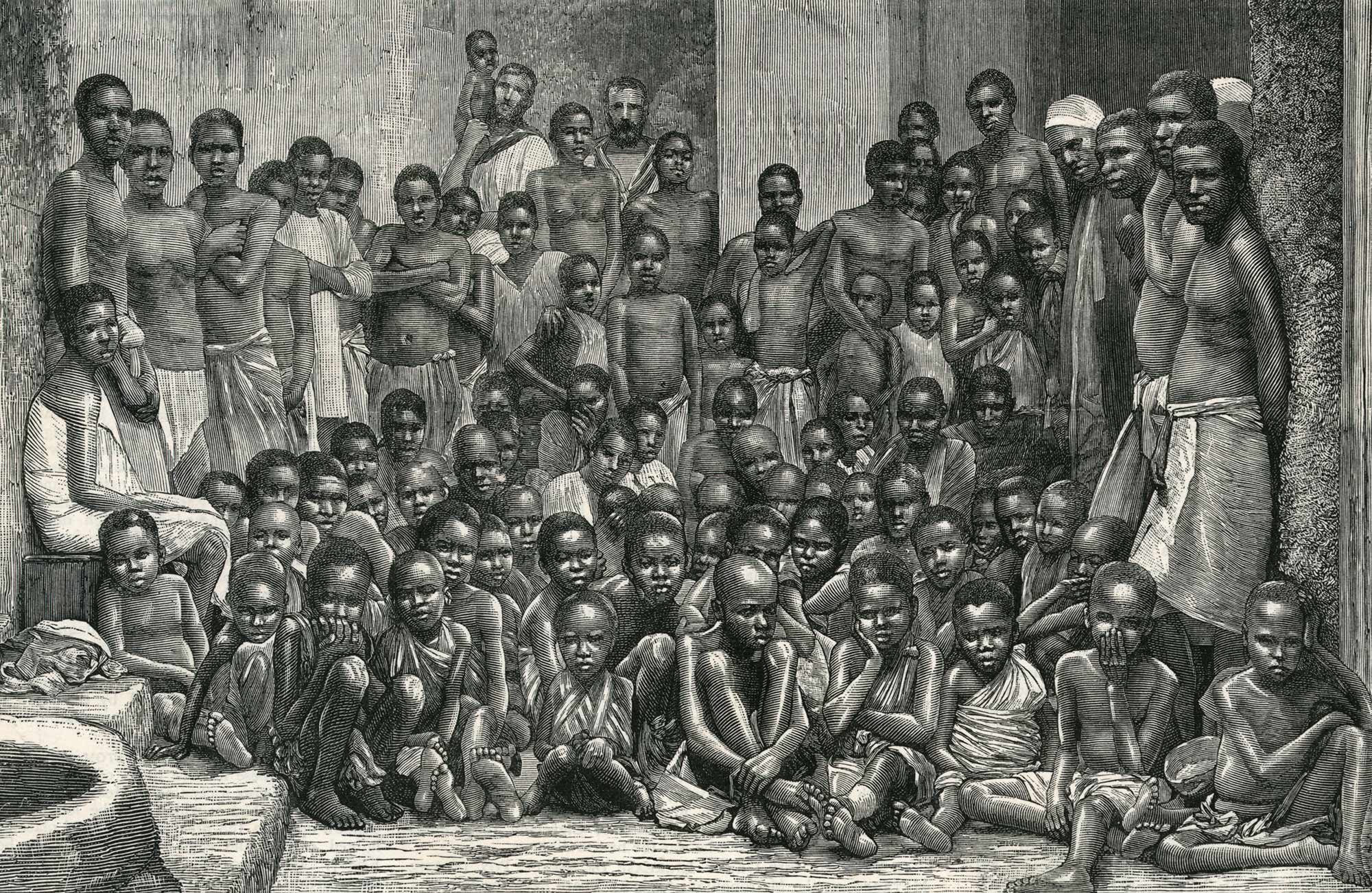

The camera doesn't lie, but it sure can be used to tell a specific story. When you look at photos of real slaves, you aren't just looking at old, grainy images from a museum archive. You're looking at the first time in human history where the absolute brutality of chattel slavery met the cold, unblinking eye of technology. It changed everything. Before photography, we had sketches. We had paintings. But those were filtered through the artist's hand. A photograph? That felt like the truth.

Honestly, it’s heavy stuff.

The Daguerreotype was the "high tech" of the 1840s and 1850s. It required the subject to sit perfectly still for a long time. Think about that. These men and women, who were legally considered property, had to sit motionless while a white photographer captured their likeness. Sometimes it was for science. Sometimes it was for "souvenirs." Sometimes, rarely, it was for justice.

The Famous Case of Gordon and the Scars

You’ve probably seen the most famous of all photos of real slaves. It’s the image of a man named Gordon (often called "Whipped Peter"). He escaped from a plantation in Mississippi and made it to a Union Army camp in Baton Rouge in 1863.

He sat for a photo.

The image shows his back. It is a map of keloid scars. Deep, crisscrossing ridges of flesh that look like a topographical map of a nightmare. When that photo was reproduced and circulated by abolitionists, it destroyed the "happy slave" myth that Southern plantation owners tried to sell to the North. You couldn't argue with a photograph. It was physical proof of a level of violence that words struggled to convey.

📖 Related: Sweden School Shooting 2025: What Really Happened at Campus Risbergska

The impact was immediate. It wasn't just "news." It was a viral moment before the internet existed. People in Boston and London looked at that photo and realized the political debate wasn't about "states' rights" or "economics"—it was about whether one human being should be allowed to do that to another.

Why These Photos Exist in the First Place

It's kinda weird to think about, right? Why would a slave owner pay for a photograph of someone they owned?

It wasn't usually out of kindness.

- Pseudo-Science: In 1850, a Harvard professor named Louis Agassiz commissioned a series of daguerreotypes of enslaved people in South Carolina. He wanted to "prove" his theory of polygenism—the idea that different races had different origins. He took photos of Renty and his daughter Delia. They are heartbreaking. They are stripped. They are vulnerable. Agassiz wasn't looking for their humanity; he was looking for biological "evidence" to justify racism.

- Identity and Runaways: Sometimes, owners took photos to help catch people if they ran away. It was basically an early version of a "Wanted" poster.

- Family "Heirlooms": In a twisted bit of history, some white families took photos of their "favorite" enslaved domestic workers or "mammies." These were often posed to show a false sense of intimacy or loyalty, masking the underlying coercion of the relationship.

The Zealy Daguerreotypes and the Fight for Ownership

Let's talk about Renty. He was a Congolese man enslaved on a plantation. His image, part of the Zealy daguerreotypes, became the center of a massive legal battle recently. Tamara Lanier, a woman who traced her ancestry back to Renty, sued Harvard University for the return of those photos.

She argued they were the "spoils of a crime."

👉 See also: Will Palestine Ever Be Free: What Most People Get Wrong

Harvard argued they owned the physical objects. This brings up a massive question in the world of history and photography: who owns the image of a person who was never allowed to own themselves? It’s not just a legal question; it’s a moral one. When we look at photos of real slaves, are we participating in their exploitation, or are we honoring their memory?

Most historians, like those at the Smithsonian or the National Museum of African American History and Culture, suggest that the context is what matters. If you use the photo to educate, to humanize, and to acknowledge the horror, you are reclaiming that person’s dignity.

Finding the Humanity in the Grain

Not every photo is a horror show. Some of the most poignant photos of real slaves are the ones taken right after emancipation.

You see the change in the eyes.

There are photos from the 1860s of former slaves wearing Union uniforms. They stand tall. They have shoes. They have a rifle. The contrast between a daguerreotype of a stripped Renty and a tintype of a Black Union soldier is the story of America in a nutshell. It’s the transition from being an "object" to being an "agent."

✨ Don't miss: JD Vance River Raised Controversy: What Really Happened in Ohio

Then there are the "Ex-Slave Narratives" from the 1930s. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) sent writers and photographers to interview the last living people who remembered slavery. These aren't just photos; they are records of survival. You see 80-year-old and 90-year-old men and women sitting on porches in the rural South. They lived to see the end of the system that tried to break them.

The Technical Reality of 19th-Century Photography

Photography back then was hard. You used glass plates or copper sheets coated in silver. It was expensive. Because of the cost and the technical difficulty, the photos of real slaves that survived are usually the ones that were backed by money or a specific political cause.

We’ve lost so much.

For every photo of Gordon or Renty, there are a million people whose faces are lost to time. We have their names on ledgers. We have their "value" in tax documents. But we don't have their faces. That’s why the few photos we do have are so precious. They are the only visual bridge we have to the millions of people who lived and died in that system.

How to Engage with This History Responsibly

If you're researching this, you've gotta be careful. The internet is full of "history" sites that don't verify their sources. Sometimes, photos of sharecroppers from the 1910s are mislabeled as "slaves." While the conditions were often similar, the historical context is different.

- Check the Source: Always look for institutional backing. The Library of Congress and the National Archives are the gold standards. They have digitized thousands of original plates and prints.

- Understand the "Pose": Remember that the person in the photo didn't choose how to stand. The photographer—usually a white man—directed the shot. Look for the small details that the photographer couldn't control: the clenching of a jaw, the positioning of hands, the weariness in the eyes.

- Acknowledge the Trauma: These aren't just "cool old photos." They are evidence of a crime against humanity. Treat them with the weight they deserve.

Practical Steps for Further Research

If you want to go deeper into the visual record of American slavery, don't just stick to Google Images.

- Visit the Library of Congress Digital Collections. Search for "Civil War Photographs" or "Gladstone Collection." The Gladstone Collection is particularly important because it contains many tintypes and ambrotypes of African Americans from the mid-19th century.

- Read "Camera Lucida" by Roland Barthes. It’s not specifically about slavery, but it’s the best book ever written on why photographs haunt us. It helps you understand the "death" that happens in every click of a shutter.

- Explore the WPA Slave Narratives. The Library of Congress has these online. You can read the transcripts of the interviews alongside the photos of the people being interviewed. It gives the faces a voice.

- Follow the Harvard/Lanier Case. Keeping up with the legal status of the Renty daguerreotypes is crucial for understanding how we handle these images in the modern era.

The history of photos of real slaves is a history of power. The power to look, the power to capture, and eventually, the power to remember. By looking at these images today, we aren't just seeing the past; we are ensuring that the people who lived through it are never truly forgotten. They aren't just statistics in a textbook anymore. They have faces. They have names. They have a legacy that still shapes the world we walk through every single day.