Search for photos of celiac disease and you’ll likely get a screen full of bright pink, fleshy tubes that look like something out of a sci-fi movie. It’s a lot to process. Most people expect to see a rash or maybe a bloated stomach, but the real "money shot" for a diagnosis happens deep inside the small intestine.

It’s weirdly beautiful in a clinical way.

But here’s the thing: those images aren't just for medical textbooks. They are the definitive proof for millions of people that their body is literally picking a fight with itself over a piece of toast. If you've been feeling like garbage every time you eat pasta, seeing those photos of celiac disease—specifically your photos from an endoscopy—can be the most validating, terrifying moment of your life. It turns an invisible "gut feeling" into a visible medical reality.

The "Shag Carpet" vs. The "Tile Floor"

Doctors love metaphors. When they talk about a healthy small intestine, they usually compare it to a plush, high-pile shag carpet. This "carpet" is made of tiny, finger-like projections called villi. Their whole job is to grab nutrients from your food as it passes by.

When you look at high-definition endoscopic photos of a healthy intestine, you see a velvety, undulating surface. It’s intricate. It’s textured.

Now, look at photos of celiac disease.

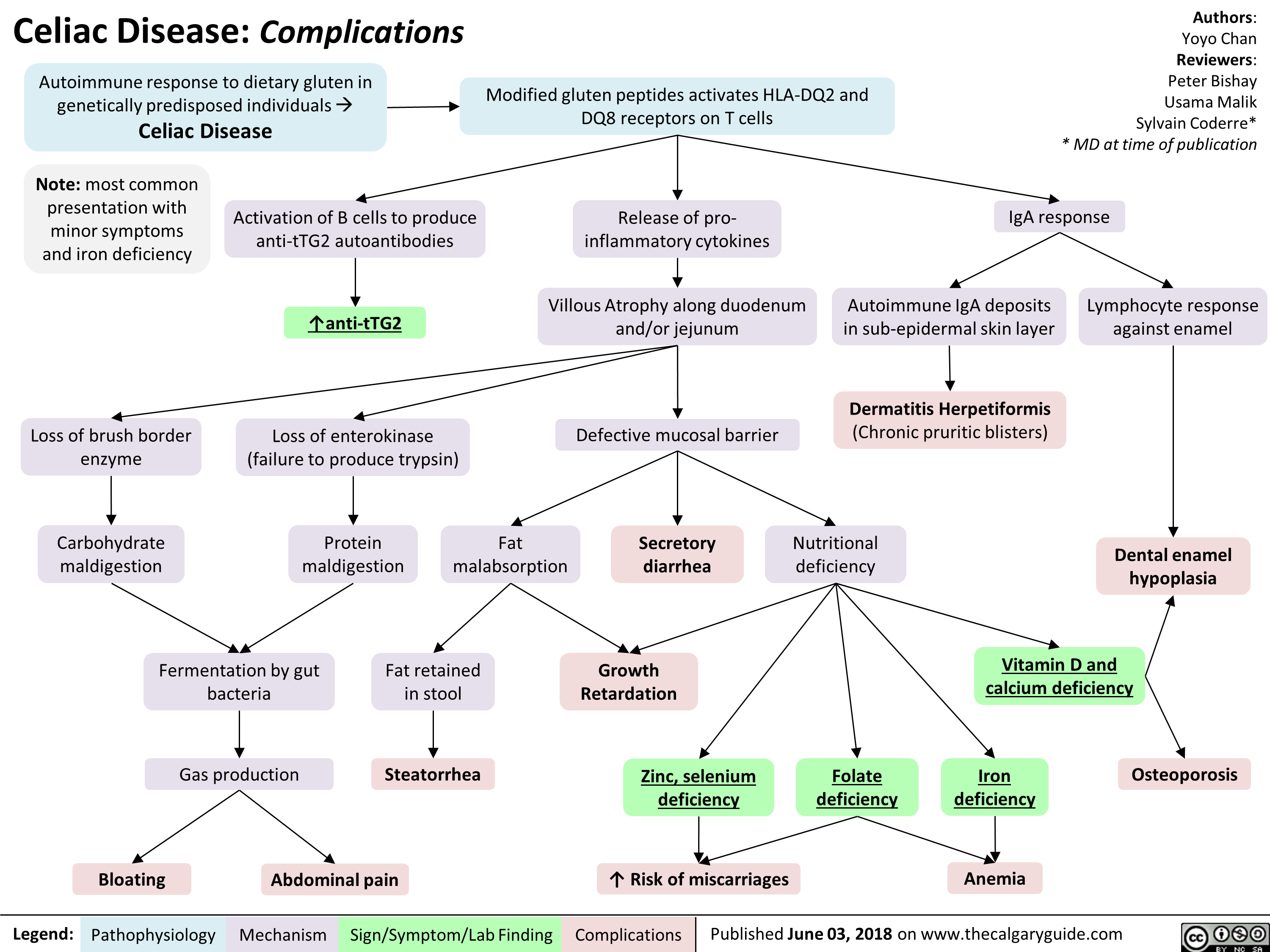

The transformation is jarring. In a person with untreated celiac, the immune system views gluten as a threat. It attacks. The result is "villous atrophy." Basically, those lush fingers get worn down until the surface of the intestine is flat and smooth, like a tile floor or a worn-out rug.

Imagine trying to soak up a spill with a flat piece of plastic versus a thick towel. That’s what’s happening in your gut. Because the surface area is gone, you can’t absorb iron, B12, or Vitamin D. You’re eating, but you're starving.

🔗 Read more: In the Veins of the Drowning: The Dark Reality of Saltwater vs Freshwater

Marsh Scores and what the camera sees

Physicians use something called the Marsh Classification to grade what they see in these photos. A Marsh 0 is a normal, healthy gut. By the time you get to Marsh 3, the villous atrophy is obvious even to an untrained eye. You’ll see "scalloping"—which looks like little notches or ridges along the circular folds of the intestine—and "mosaicism," a cracked-earth pattern that looks like a dry lake bed.

It’s honestly wild how much damage a tiny protein can do.

Why images aren't always enough

You might think, "Okay, if the camera shows the damage, why do I need a biopsy?"

It’s a fair question.

Visuals can be misleading. Sometimes the damage is "patchy." A doctor might point the camera at one spot that looks totally fine, while two inches away, the villi are completely decimated. This is why the Gold Standard for diagnosis—according to major organizations like the Celiac Disease Foundation and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN)—is taking multiple tissue samples.

Usually, they take four to six snips.

A photo tells a story, but the pathology report under a microscope provides the ending. You can have "macroscopic" (visible to the eye) signs, but the "microscopic" details are what confirm the presence of intraepithelial lymphocytes—basically, the foot soldiers of the immune system that shouldn't be there in such high numbers.

💡 You might also like: Whooping Cough Symptoms: Why It’s Way More Than Just a Bad Cold

Skin deep: The photos of celiac disease you can see in the mirror

Not all celiac photos are of internal organs.

Dermatitis Herpetiformis (DH) is the "skin version" of celiac disease. If you’ve ever seen photos of this, you won't forget them. It isn't just a regular itchy rash; it’s a collection of stinging, blister-like bumps that usually show up on the elbows, knees, or buttocks.

It’s incredibly specific.

If you have these photos of your skin and a biopsy confirms DH, you have celiac disease. Period. You don't even technically need the gut biopsy at that point because the skin reaction is a direct result of the same gluten intolerance. Dr. Alessio Fasano, a titan in the world of celiac research at Massachusetts General Hospital, has often pointed out how these external symptoms are just the tip of the iceberg for what's happening internally.

The deceptive "bloat" photo

Social media is flooded with "celiac bloat" photos. You’ve seen them: someone looks six months pregnant in one photo and has a flat stomach in the next.

While these are visceral and relatable, they are the least "medical" photos of celiac disease. Bloating is a symptom of a hundred different things—IBD, SIBO, food sensitivities, or just a heavy meal. While the "gluten belly" is very real for patients, doctors can’t diagnose you based on a selfie.

The internal photos are the ones that carry the weight.

📖 Related: Why Do Women Fake Orgasms? The Uncomfortable Truth Most People Ignore

Healing is visible too

The coolest part? This damage isn't always permanent.

If you look at follow-up photos of celiac disease after a patient has been on a strict gluten-free diet for a year or two, the transformation is incredible. The villi often grow back. The "tile floor" starts looking like a "carpet" again.

It’s one of the few autoimmune conditions where you can actually see the body repairing itself once the trigger is removed. However, healing isn't instantaneous. For adults, it can take years for the intestinal lining to return to a completely normal state. In some cases of "refractory celiac disease," the damage persists even without gluten, which is why those follow-up images are so crucial for long-term health monitoring.

Actionable steps for the concerned

If you’ve been looking at photos of celiac disease because you suspect you have it, do not just stop eating gluten today. That is the biggest mistake people make. If you stop eating gluten before your tests, your gut will start to heal, and the photos/biopsies will come back "normal," even if you’re actually sick.

1. Stay on the "Gluten Challenge"

You need to be eating the equivalent of about two slices of wheat bread every day for 6–8 weeks before an endoscopy. This ensures the "damage" is visible for the camera.

2. Get the Serology First

Ask for a tTG-IgA blood test. It’s the screening tool that usually leads to the endoscopy. If those numbers are high, your doctor will likely schedule the procedure to get those internal photos.

3. Request "High-Definition" Endoscopy

If your hospital has it, i-SCAN or narrow-band imaging (NBI) can make the villi much easier to see. These technologies use specific light wavelengths to highlight the texture of the intestinal wall, making it way easier for the GI doctor to spot patchy damage.

4. Document your "External" Photos

If you have a rash or specific dental enamel defects (another weird celiac sign), take photos of them. Show them to your dermatologist or dentist. Sometimes the path to a gut diagnosis starts with a skin or tooth photo.

5. Keep Your Own Copy

Always ask for the printed images from your procedure. It’s your body. Having those photos of celiac disease in your personal records is vital if you ever switch doctors or need to prove your diagnosis for insurance or clinical trials in the future.