Walk into any major stock photo agency’s office ten years ago, and you’d likely find a very specific, very narrow set of images representing an entire continent. It was frustrating. You’ve probably seen them: the "poverty porn," the endless savannahs with a lone acacia tree, or the hyper-exoticized tribal portraits that look more like museum exhibits than living people. But things are shifting. Lately, the way we produce and consume photos of African people has undergone a massive, long-overdue overhaul. It’s not just about "better" pictures; it's about who is behind the lens and what stories they are actually allowed to tell.

The internet is finally catching up to the reality that Africa isn't a monolith.

For a long time, the global North controlled the visual narrative. This created a weird, distorted mirror. When you searched for a "businessman" in a stock library in 2015, you’d get thousands of results from London or New York, but maybe three from Lagos or Nairobi. And those few were often staged in ways that felt... off. Artificial. Today, photographers like Prince Gyasi and Stephen Tayo are flipping that script entirely. They aren't just taking photos; they’re reclaiming a visual identity that was hijacked for decades.

The problem with the "Single Image" legacy

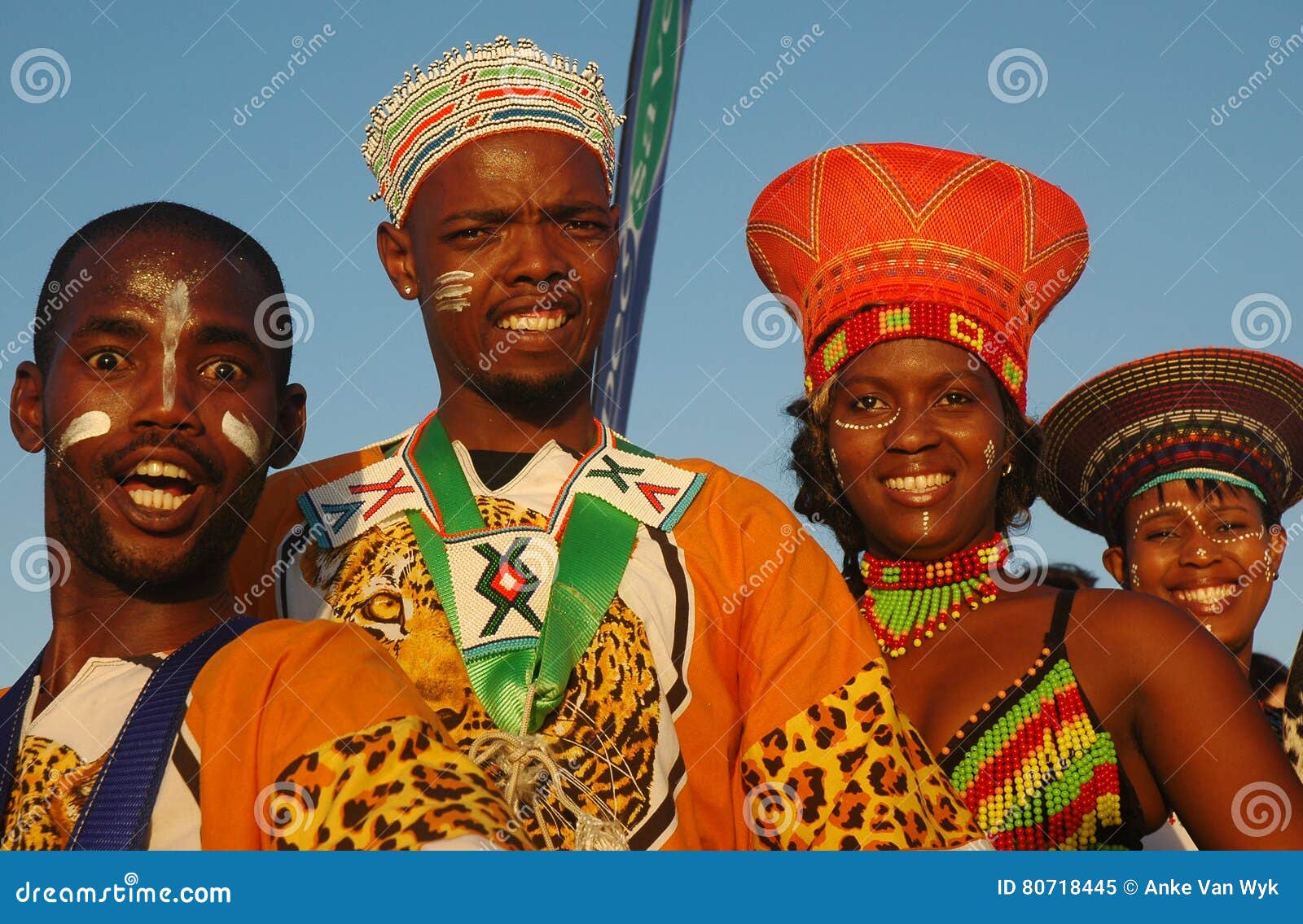

We have to talk about the "National Geographic" effect. For nearly a century, that specific aesthetic defined what photos of African people looked like to the rest of the world. It focused on the "other." It looked for the scarification, the traditional beads, and the mud huts. While those things are real and culturally significant, they were often presented without context, making 1.4 billion people look like they lived in a permanent state of the 19th century.

It was a visual lie by omission.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie famously spoke about the "danger of a single story." This applies perfectly to photography. If you only see photos of African people looking hungry or "exotic," you lose the ability to imagine them as software engineers, skaters, fashionistas, or neurosurgeons. Honestly, it’s boring. The world is tired of the same three tropes. People want authenticity now. They want to see the traffic in Luanda, the brunch scene in Accra, and the tech hubs in Kigali.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

The rise of homegrown stock photography

Because the big players like Getty and Shutterstock were slow to diversify, African entrepreneurs just did it themselves. Platforms like Picha Stock and PhotoVibe emerged specifically to fill this gap. They realized that African brands needed imagery that actually looked like their customers. Think about it. If you’re a bank in Ghana, you can’t use a stock photo of a family that clearly looks like they’re in a suburb in Ohio. It doesn't work. It kills trust.

- Picha Stock focuses on Afrocentric visuals that cover modern life.

- Everyday Africa, a massive collaborative project on Instagram, started as a way for photographers to capture the mundane. The "boring" stuff. A guy getting a haircut. A woman waiting for a bus. A kid playing with a plastic bottle.

- These images are revolutionary precisely because they are ordinary.

Basically, the "ordinary" is what was missing. When you look at photos of African people today, you’re starting to see the middle class. You're seeing the urban hustle. This shift is driven by a younger generation of photographers who have high-end gear and a very low tolerance for stereotypes. They are using light and color—especially high-contrast saturation—to celebrate Black skin in ways that film stock historically failed to do.

The technical side: Why film struggled with Black skin

Here is a bit of nerd history that most people don't know. For decades, color film was calibrated using something called "Shirley cards." These were reference cards featuring a white woman (named Shirley) used by lab technicians to balance skin tones. Because the chemistry was optimized for light skin, it often made darker skin tones look muddy, greenish, or just plain grey.

It wasn't until the 1970s and 80s—partly because chocolate makers and wood furniture manufacturers complained that their products didn't look right in ads—that Kodak and others adjusted the chemistry.

Modern digital sensors are much better, but there's still a learning curve. Taking great photos of African people requires understanding how dark skin reflects light. It’s not about "brightening" the subject. It’s about capturing the highlights—the golds, the purples, and the rich browns. Digital creators are now sharing tutorials specifically on color grading for melanin, ensuring that the vibrancy of the person isn't lost in the digital process.

🔗 Read more: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

Why representation actually affects the bottom line

From a business perspective, getting this right isn't just "woke" branding; it’s smart economics. Africa has the youngest population on earth. By 2050, one in four people on the planet will be African. If your marketing department is still using outdated photos of African people, you’re effectively alienating the world's fastest-growing consumer market.

I’ve seen dozens of ad campaigns fail because they used "generic" African imagery that locals immediately recognized as being from a different region entirely. Africa is a continent of 54 countries. A photo of someone in a Kente cloth (Ghanaian) doesn't make sense for a campaign targeting people in Ethiopia or Morocco. It’s like using a photo of a man in a kilt to advertise to someone in Naples. People notice.

Digital activism and the Instagram effect

Instagram changed everything. Suddenly, you didn't need a gallery deal or a magazine editor’s permission to show your world. Hashtags like #EverydayAfrica or #VisiterLAfrique allowed local photographers to bypass the traditional gatekeepers.

You see it in the work of photographers like Mulugeta Ayene or Sarah Waiswa. Their photos of African people often blend documentary styles with high-fashion sensibilities. They aren't asking for permission to be seen; they are just showing up. This has forced major media outlets to change their hiring practices. You’re seeing more "local stringers" getting the lead photo credits in the New York Times or the BBC, which changes the perspective of the news itself.

It's less "us looking at them" and more "them telling us what’s happening."

💡 You might also like: Sleeping With Your Neighbor: Why It Is More Complicated Than You Think

How to find and use authentic imagery

If you’re a creator, a blogger, or a business owner looking for photos of African people, don't just take the first result on a free stock site. You have to look deeper. Look for photographers who are actually based in the regions they are shooting.

- Check the metadata. Does the photo actually say where it was taken? "African man smiling" is a bad sign. "Entrepreneur in Nairobi's central business district" is much better.

- Avoid the "poverty lens." Unless you are specifically writing a report on humanitarian aid, avoid images that focus solely on struggle. It’s a lopsided view of reality.

- Look for diversity in age and setting. There’s more to the continent than kids playing in dirt or young techies in offices. Where are the elderly? Where are the suburban gardens? Where is the nightlife?

- Support African creators directly. Buy licenses from platforms that prioritize African contributors. This ensures the money goes back into the ecosystem that produced the art.

The future is vibrant

We are moving toward a world where "African photography" isn't a niche category. It’s just photography. As AI-generated imagery starts to flood the market, the value of authentic, human-captured photos of African people is actually going to skyrocket. AI still struggles with the nuances of culture—it often hallucinates stereotypes because it’s trained on the very biased data we’re trying to move away from.

The real magic is in the specific. It’s in the way a 특정 (specific) fabric drapes, the way the light hits a dusty street in Bamako at 4:00 PM, or the genuine laugh of a grandmother in Lagos. You can't faked that.

To truly engage with African visuals, you have to stop looking for what you expect to see and start looking at what is actually there. The diversity is staggering. The talent is immense. And the photos are finally starting to do justice to the people they represent.

Actionable Insights for Navigating African Visuals:

- Audit your current assets: If you run a website or social feed, look at your imagery. Is it 90% Western? If you have African imagery, is it diverse or just a "token" photo?

- Follow local hubs: Start following accounts like @amfostories or @everydayafrica to recalibrate your internal "visual compass" of what the continent looks like.

- Prioritize context: When captioning or using photos of African people, include the specific country or city whenever possible. It fights the "monolith" myth.

- Use specialized agencies: Move beyond the "Big Three" stock sites and explore Picha Stock, Tonl, or Nappy.co for more nuanced representations of Black life globally and on the continent.

- Understand the legalities: Ensure that when using photos of people, especially in sensitive contexts, you are using images with proper model releases to respect the dignity and rights of the subjects.