You’ve probably seen the photo. A woman sits in a bathtub, scrubbing her shoulder with a washcloth. Her face is a mask of weary determination. On the bathmat, a pair of heavy, mud-caked combat boots sit on the pristine white tile.

What most people don't realize is that this isn't just any bathroom. It's Adolf Hitler’s private apartment in Munich. And those boots? They’re covered in the dust of Dachau, the concentration camp she’d just left hours before.

Honestly, photographs of Lee Miller shouldn't exist in the way we have them today. If it weren't for her son, Antony Penrose, finding 60,000 negatives and manuscripts tucked away in an attic in 1977, we might only remember her as a pretty face on a Vogue cover. She never talked about her work. Not to her family, not to her friends. She just boxed up the trauma and the genius and became a gourmet cook in the English countryside.

The Girl Who Refused to be Just a Muse

Lee Miller didn't just fall into photography. She stormed into it.

After a modeling career in New York that basically ended because she appeared in a then-taboo advertisement for menstrual products—a scandal that would seem ridiculous now but was career-ending in 1929—she moved to Paris. She didn't want to be in front of the lens anymore. She wanted to be behind it.

She tracked down Man Ray, the legendary Surrealist. The story goes she told him, "I’m your new student." He told her he didn't take students. She stayed anyway.

They became lovers, sure, but they were mostly a powerhouse creative team. They "discovered" solarization together—that weird, halo-like effect where darks and lights are reversed. It happened by accident when a mouse ran over Lee’s foot in the darkroom and she switched on the light. Instead of panic, she saw art.

✨ Don't miss: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

You can see this in her early Surrealist work.

- Exploding Hand (1930): A shot of a hand through a glass window that looks like it’s shattering the very air.

- Portrait of Space (1937): A torn mosquito net in the Egyptian desert that creates a "frame within a frame," making the horizon look like a dream.

Why Photographs of Lee Miller Changed During the War

When World War II broke out, everyone expected Miller to go back to the States. She didn't. She stayed in London and started shooting for British Vogue.

But she wasn't interested in hats and gloves.

She started documenting the Blitz. She photographed typewriters smashed by falling masonry and searchlights cutting through the night. Eventually, she became an accredited war correspondent for the U.S. Army. This was unheard of. A fashion model in the mud? People thought she was crazy.

She wasn't. She was focused.

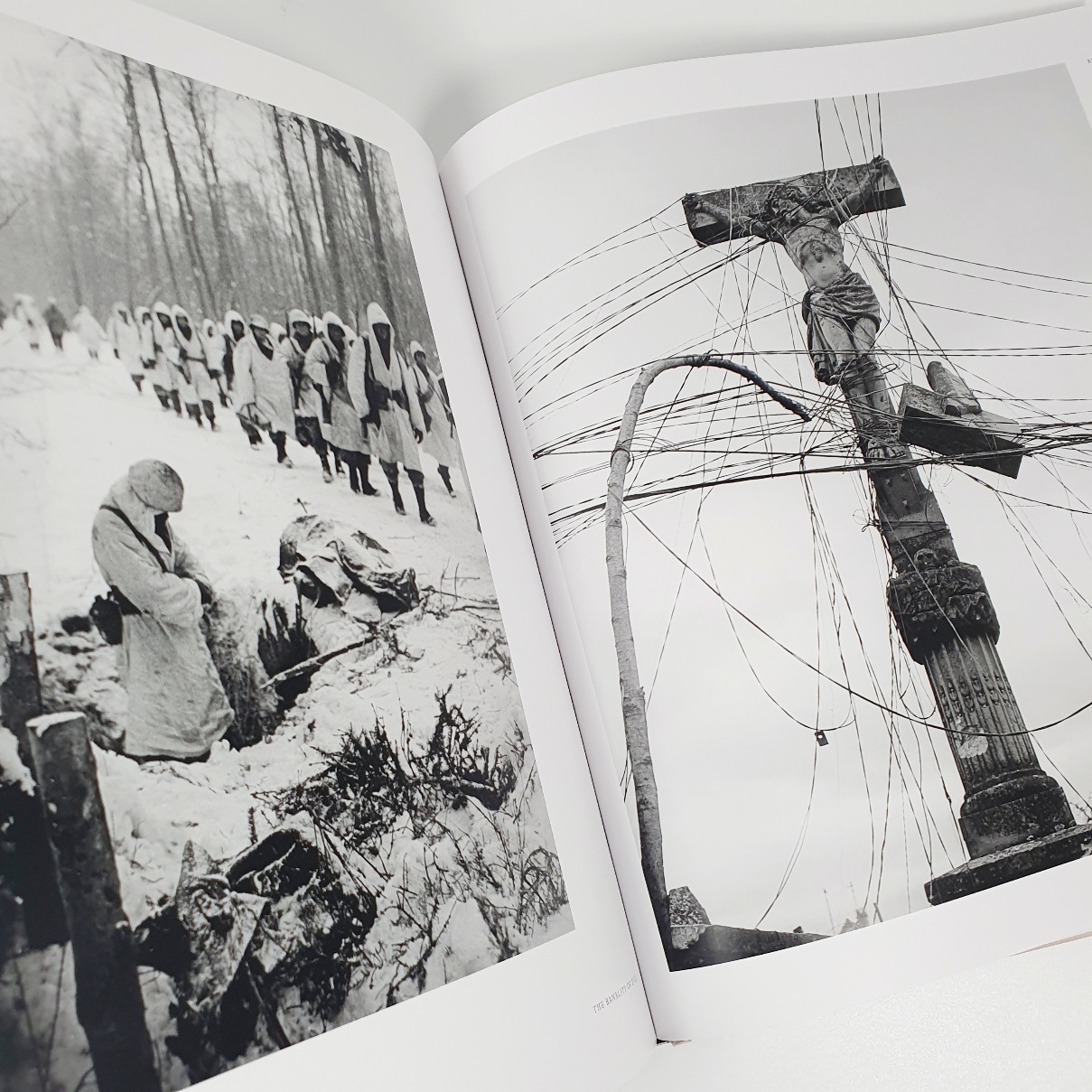

Miller’s wartime photographs are jarring because she applied her Surrealist eye to the most horrific reality imaginable. While other photographers kept their distance, Lee got close. Very close.

🔗 Read more: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

The Bathtub and the "Believe It" Series

On April 30, 1945, Lee Miller and fellow photographer David E. Scherman entered Hitler’s abandoned apartment. They were exhausted. They smelled like the death they had just witnessed at the liberation of Dachau and Buchenwald.

The bathtub photo was a deliberate act of desecration. By placing her filthy boots on the dictator's mat and washing the grime of a concentration camp in his tub, she was reclaiming humanity from a monster.

But the "Believe It" series for Vogue was the real turning point.

When Lee sent her photos of the camps back to the editors, they were hesitant. They were a fashion magazine, after all. Lee sent a cable that basically said: BELIEVE IT. She demanded they show the piles of clothes, the skeletal survivors, and the open ovens.

She wanted to make sure no one could ever say they didn't know.

Life After the Lens: The Attic Legacy

After the war, Lee Miller developed what we would now call severe PTSD. She struggled with depression and alcoholism. She married the artist Roland Penrose, moved to Farley Farm House in Sussex, and essentially buried Lee Miller the photographer.

💡 You might also like: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

She became a legendary hostess and a Cordon Bleu chef, famous for making blue spaghetti and hosting people like Picasso.

When she died in 1977, her son found the boxes. Tens of thousands of images. Portraits of Picasso. Fashion shoots. Horrific war reportage. The entire history of the 20th century was sitting in his attic under a layer of dust.

How to Explore Her Work Today

If you're looking to dive deeper into her portfolio, don't just look for the "famous" shots. Look for the nuance.

- Visit Farleys House and Gallery: This is her former home in East Sussex. You can see where she lived and see rotating exhibitions of her work. It’s a pilgrimage for anyone who cares about 20th-century art.

- Study the Solarization: Look at the way she and Man Ray played with light. It’s a masterclass in how "mistakes" in the darkroom can lead to entirely new art forms.

- Read "Lee Miller’s War": This book, edited by her son Antony Penrose, compiles her dispatches and photos. It’s raw, it’s difficult, and it’s necessary.

- Look for the "Surrealist Eye": Even in her fashion work, look for the odd angles and the strange shadows. She never stopped being a Surrealist; she just changed her subject matter.

Miller once said that she "never wasted a minute." Looking at her output, it's hard to argue with that. She lived about five different lives in the span of one, and every single one of them was captured in silver halide and shadow.

The best way to honor her legacy is to look at the photos she didn't want the world to forget—the ones that prove, even in the middle of a nightmare, someone was there to keep the lights on and the shutter clicking.

Next Steps for Research:

You should look into the specific archives held at Farleys House, as they contain the original manuscripts of her war dispatches, which provide the essential written context for her most harrowing images. Additionally, comparing her 1930s New York studio work with her Paris collaborations reveals how she adapted commercial lighting techniques into high-concept Surrealist art.