You're sitting in the exam hall. The clock is ticking. You flip to the Free Response Questions and there it is—a prompt asking you to shift a curve based on an "unexpected increase in consumer spending." If you don't know the Phillips Curve AP Macroeconomics relationship, you're basically guessing. But here's the thing: it isn't just some dusty graph from the 1950s. It’s the heartbeat of how the Federal Reserve actually makes decisions about your bank account, your future mortgage, and whether or not you'll find a job after graduation.

A.W. Phillips wasn’t even an economist by trade. He was a New Zealand-born engineer who looked at British wage data and noticed something weird. When unemployment was low, wages rose fast. When unemployment was high, wage growth slowed to a crawl. He drew a line. That line changed everything.

In the world of AP Macro, the Phillips Curve is the mirror image of your Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply (AD/AS) model. If you move a dot along the Short-Run Aggregate Supply curve, you’re moving a dot along the Short-Run Phillips Curve (SRPC). They are two sides of the same coin. Understanding this isn't just about passing a test; it's about understanding why the government sometimes intentionally slows down the economy.

The Short Run: A High-Stakes Balancing Act

The SRPC shows an inverse relationship. Inflation goes up? Unemployment goes down. It feels like a deal with the devil. When people spend more money, businesses hire more workers to keep up with demand. That’s great for the unemployment rate. However, all that hiring and spending pushes prices higher.

Suddenly, you have inflation.

📖 Related: What Really Happened With Trump Revoking Mayorkas Secret Service Protection

Think about the late 1960s in the United States. President Lyndon B. Johnson was spending big on the "Great Society" programs and the Vietnam War simultaneously. Unemployment plummeted to below 4%. It was a boom. But, as any Phillips Curve AP Macroeconomics student could tell you, the bill eventually came due in the form of skyrocketing price levels.

When you're drawing this on your exam, remember that a shift in Aggregate Demand (AD) causes a movement along the SRPC.

- If AD shifts right (expansion), you move up and to the left on the SRPC (higher inflation, lower unemployment).

- If AD shifts left (recession), you move down and to the right (lower inflation, higher unemployment).

But what happens when the curve itself moves? That’s where things get messy. If the Short-Run Aggregate Supply (SRAS) shifts, the entire SRPC shifts in the opposite direction. If SRAS moves left (stagflation), the SRPC moves right. This is the worst-case scenario. You get higher inflation and higher unemployment at the same time. This actually happened in the 1970s during the oil shocks. It broke the brains of economists who thought the Phillips Curve was a permanent menu of options. It wasn't.

The Long Run and the Natural Rate of Unemployment

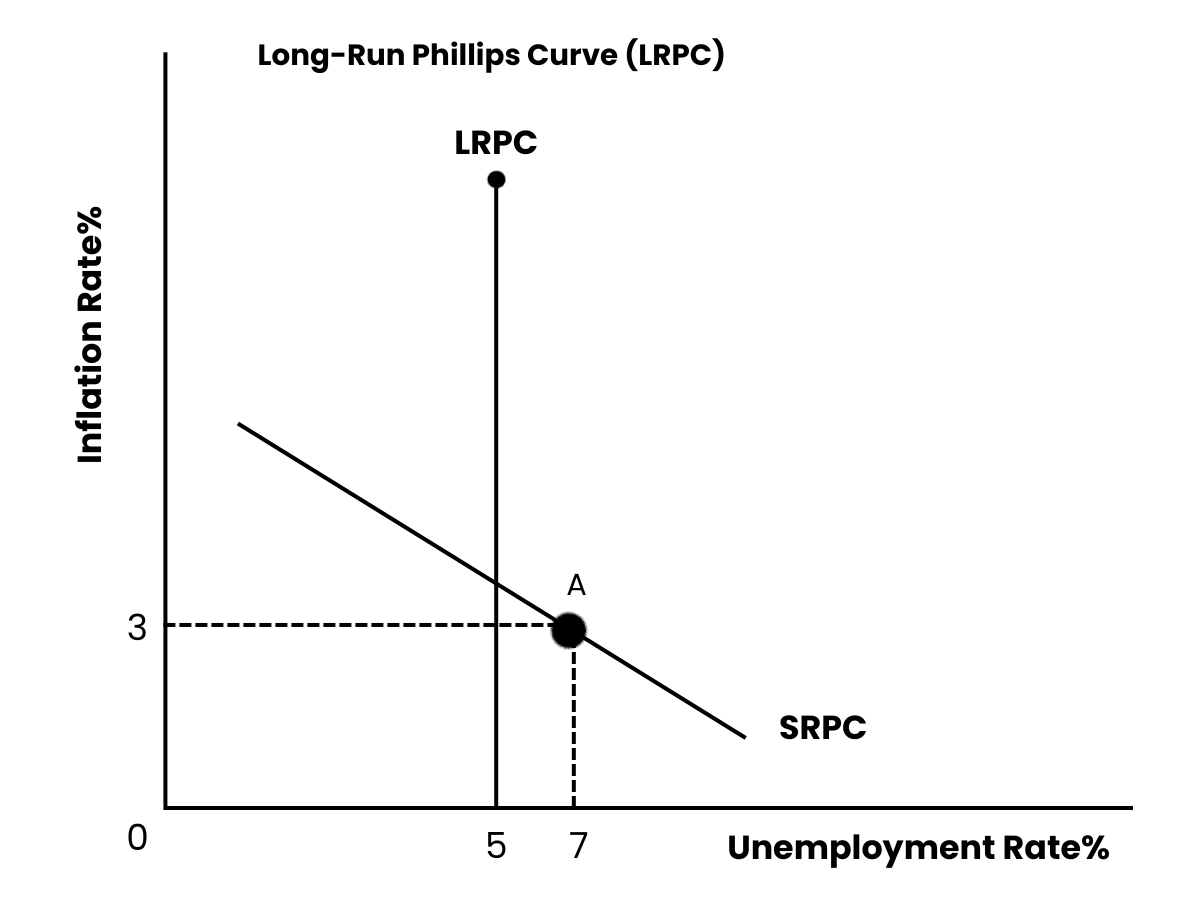

The Long-Run Phillips Curve (LRPC) is a vertical line. It sits right at the Natural Rate of Unemployment (NRU). Why vertical? Because in the long run, there is no trade-off. You can't just print money forever to keep unemployment at zero. Eventually, people expect the inflation. They ask for higher wages. The "oomph" of the extra money disappears.

👉 See also: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

If the actual unemployment rate is to the left of the LRPC, the economy is overheating. It’s an inflationary gap. If it’s to the right, we’re in a recessionary gap.

The LRPC represents the "Full Employment" level. It only moves if the NRU moves. If the government changes unemployment benefits or if there’s a massive shift in technology that makes job-hunting more efficient, that vertical line might budge. Otherwise, it's anchored. It's the "North Star" that the economy eventually returns to after the SRPC drama settles down.

Why Expectations Change Everything

Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps were the ones who really hammered this home. They argued that people aren't stupid. If the government tries to trick people into working more by creating inflation, workers will eventually catch on. They’ll adjust their "inflationary expectations."

When expectations rise, the SRPC shifts up. This is a crucial point for the Phillips Curve AP Macroeconomics curriculum. It explains why we can't just stay at 2% unemployment forever. The economy has a "natural" speed limit. Try to go faster, and you just end up with higher prices, not more stuff.

✨ Don't miss: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

Practical Examples for the FRQ

Let's look at a real scenario you might see.

Imagine the government increases personal income taxes. This reduces disposable income. AD shifts left. On your Phillips Curve graph, you would show a movement down the SRPC. Unemployment rises, inflation falls. Simple.

But what if energy prices double? This is a "supply shock." SRAS shifts left. Now, you must shift the SRPC to the right. Both inflation and unemployment are higher. This is the "Stagflation" trap. Knowing when to move along the curve versus when to shift the curve is the difference between a 2 and a 5 on the exam.

- Move along the curve when AD changes.

- Shift the curve when SRAS changes or inflation expectations change.

Actionable Steps for Mastering the Phillips Curve

To truly internalize this for the AP exam, stop trying to memorize the shifts. Start visualizing the AD/AS model first.

- Always draw AD/AS and Phillips Curve side-by-side. If you move the equilibrium to the right in AD/AS, move your point to the left (upward) on the SRPC. They must always tell the same story.

- Label the LRPC with the NRU. If the problem says the Natural Rate of Unemployment is 5%, that vertical line is exactly at 5% on the x-axis.

- Remember the "Double Shift" rule. If the LRPC shifts, the Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) curve must also shift. They are fundamentally linked to the economy's productive capacity.

- Practice the "Expectations" prompt. If the question says "inflationary expectations have decreased," shift the SRPC down (to the left). This means for any given level of unemployment, inflation is now lower because people don't expect prices to rise so fast.

Mastering the Phillips Curve AP Macroeconomics isn't just a hurdle. It's the key to understanding the tug-of-war between the Fed and the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. When you see the next jobs report on the news, you won't just see a number; you'll see a dot moving along a curve. That's when you know you've actually learned it.

Start by taking a blank sheet of paper and drawing the four main scenarios: an increase in AD, a decrease in AD, a negative supply shock, and a positive supply shock. If you can map those to the Phillips Curve without checking your notes, you're ready.