Ever feel like you’re just repeating the same arguments with your kids that you had with your own parents thirty years ago? It’s exhausting. You swore you’d be the "chill" parent, yet here you are, hovering or snapping over a spilled juice box.

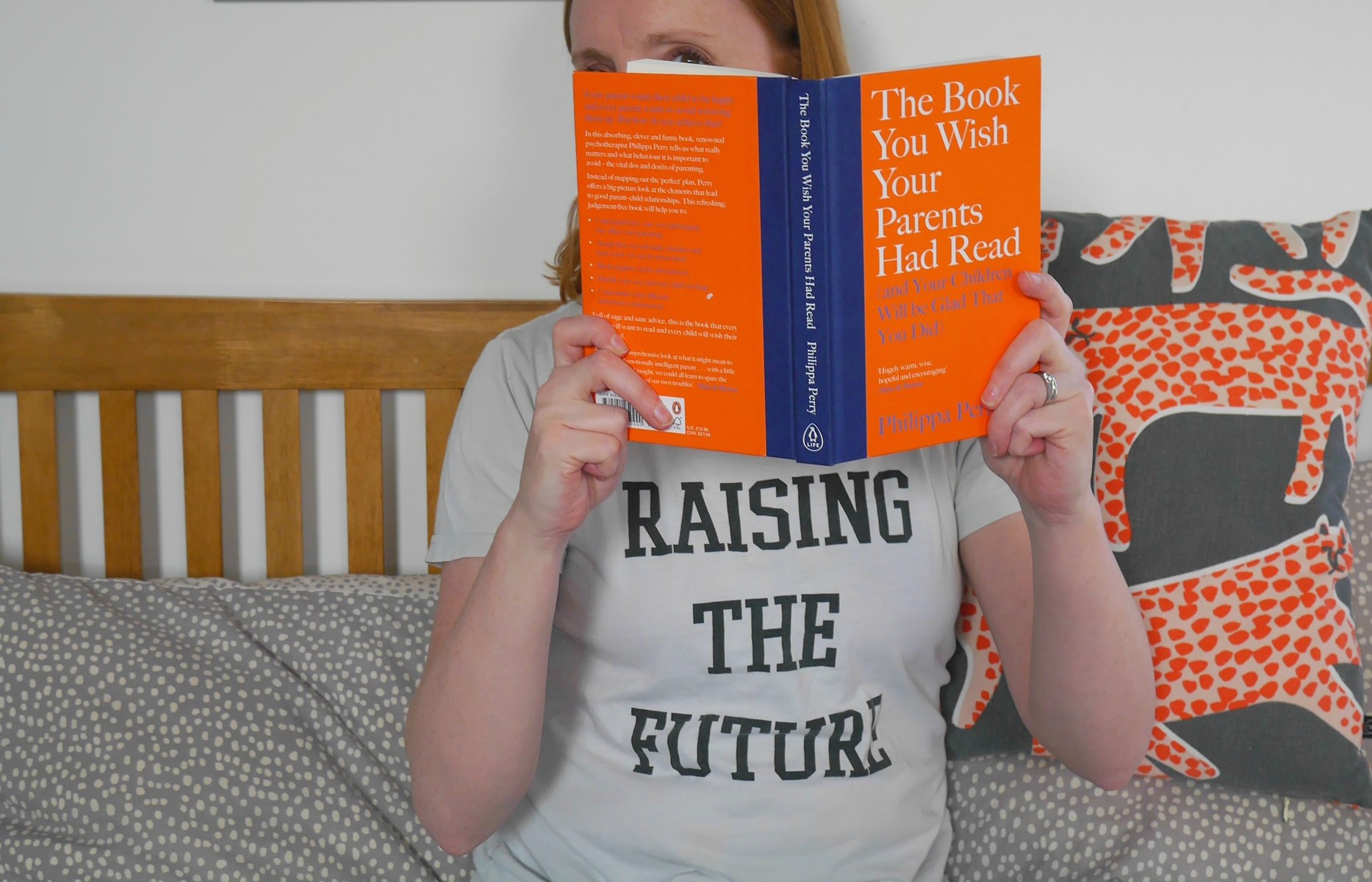

Philippa Perry, a British psychotherapist with decades of experience, wrote The Book You Wish Your Parents Had Read (and Your Children Will Be Glad That You Did) to tackle exactly this. It isn’t a manual on how to get a toddler to eat broccoli. Honestly, if you’re looking for a "how-to" on sleep training or potty schedules, this isn't it. This book is about the relationship. It’s about the messy, emotional undercurrents that dictate how we treat the people we love most.

The Rupture and the Repair

Most parenting books focus on the child’s behavior. Perry flips the script. She focuses on the parent’s history.

One of the most profound concepts in The Book You Wish Your Parents Had Read is the idea of "rupture and repair." No one is a perfect parent. You will lose your temper. You will be distracted by your phone when your child is trying to show you a drawing. You will say things you regret. According to Perry, the damage isn't in the mistake itself; it's in the failure to acknowledge it.

When a rupture happens—a disconnect or a moment of anger—the child feels unsafe or misunderstood. If we just move on and pretend it didn't happen, the child is left to process that distress alone. Perry argues that "repairing" the relationship by apologizing and explaining your own feelings (without blaming the child) is the most important thing you can do. It teaches them that relationships can be mended. It shows them that conflict isn't the end of the world.

Think about your own childhood. Did your parents ever say, "I'm sorry I yelled, I was stressed about work and I took it out on you"? Probably not. For most of us, that's a radical concept.

Stop Trying to "Fix" Feelings

We have this weird urge to make our kids happy all the time. If they're crying because their blue sock is missing, we try to distract them. "Look at this shiny toy!" or "It's just a sock, don't be silly."

💡 You might also like: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Perry points out that this is actually a form of gaslighting.

By dismissing the "silly" feelings, we teach children that their internal reality is wrong. We teach them to suppress. Instead, The Book You Wish Your Parents Had Read suggests "containing" the emotion. This means acknowledging it. "You're really upset about that sock, aren't you? It’s hard when things don’t go the way we want." You don't have to find the sock. You just have to be there while they're sad about it.

It sounds simple. It is incredibly difficult in practice.

Why Your Kids Trigger You

Ever wonder why a specific whine or a certain look from your child makes you see red? Perry explains that these are often "ghosts from the nursery."

When our children reach an age where we experienced some kind of trauma or emotional neglect, their behavior triggers those old, buried memories. If you weren't allowed to express anger as a six-year-old, seeing your six-year-old have a meltdown might feel intolerable. You aren't reacting to the kid; you're reacting to your own past.

The Problem with "Behavior Management"

The industry of parenting advice is obsessed with stickers, time-outs, and rewards. Perry is skeptical.

📖 Related: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

She argues that these tactics treat children like pets to be trained rather than humans to be related to. If you use a reward system, the child learns to do the "right" thing for the prize, not because they understand the impact of their actions on others. It’s a short-term fix that can erode long-term intrinsic motivation.

Basically, if we focus on the "why" behind the behavior, the "how" of fixing it becomes much clearer. A child hitting a sibling isn't "bad." They're likely feeling overwhelmed, jealous, or unheard. If you just punish the hitting, you haven't touched the jealousy. It’ll just come out in a different, maybe sneakier, way later.

Breaking the Cycle of Perfectionism

There is a section in the book that hits home for almost everyone: the pressure to be a "perfect" parent. Perry is very clear that striving for perfection is actually harmful.

Children don't need perfect parents. They need "good enough" parents who are authentic. If you are always "on" and never show vulnerability, your child learns that they also have to be perfect to be loved. That’s a heavy burden for a kid to carry.

Communication isn't just talking

We often talk at our children instead of with them.

- The Lecture: "You need to do this because it's good for your future..."

- The Command: "Put your shoes on now."

- The Validation: "I see you're struggling with those laces."

Perry encourages the third option. It’s about creating a "shared reality." When a child feels like you actually see them—not just who you want them to be, but who they are right now—the cooperation usually follows naturally. It’s not magic, but it feels like it.

👉 See also: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

The Impact of Environment

While the book is deeply psychological, it doesn't ignore the practicalities. The "environment" isn't just the house you live in; it's the emotional atmosphere.

If the adults in the house are constantly bickering or living in a state of high stress, the children will absorb that. You can't tell a child to "calm down" if the household feels like a pressure cooker. Perry emphasizes that taking care of your own mental health and your adult relationships is, ironically, one of the best things you can do for your parenting.

Real-World Application: What to Do Next

Reading The Book You Wish Your Parents Had Read is usually a bittersweet experience. You start to see all the ways your own parents let you down, but you also see all the ways you might be letting your kids down.

Don't panic.

The beauty of Perry’s philosophy is that it’s never too late. Even if your children are adults, you can still "repair." You can still have those conversations about the past.

Here is how to actually use these insights today:

- Observe your triggers. The next time you feel an explosive level of anger at a minor incident, stop. Ask yourself: "How old do I feel right now?" Usually, it’s not thirty-five. It’s five. Acknowledging that the anger belongs to your past can help you stay present for your child.

- Practice the "I" statement apology. If you snap, wait until you've cooled down and say: "I’m sorry I raised my voice. I was feeling frustrated because I’m tired, but it wasn’t your fault and I shouldn't have yelled."

- Validate before you redirect. Before you try to solve a problem or stop a tantrum, say out loud what the child is feeling. "You're really disappointed that we have to leave the park." Wait for them to feel heard before you move toward the car.

- Edit your internal monologue. Stop labeling your child as "difficult," "stubborn," or "lazy." These labels become self-fulfilling prophecies. Replace them with "having a hard time" or "needs more support."

- Focus on the connection, not the compliance. At the end of the day, ask yourself: "Did we connect today?" rather than "Did they do everything I told them to do?"

The goal isn't to be a saint. It's to be a person who is willing to look at their own shadows so their children don't have to live in them. It's a long game. It’s hard work. But as Perry notes, it’s the most important work we’ll ever do.