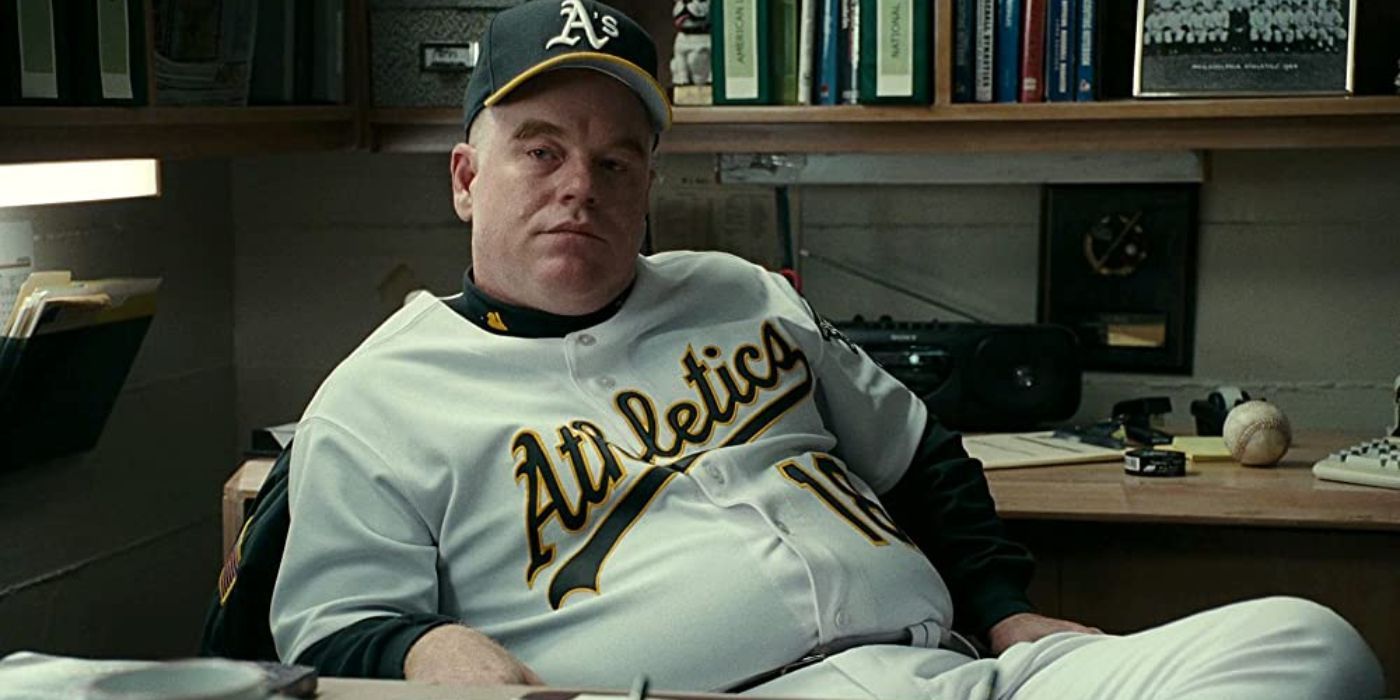

If you watch Moneyball today, it’s hard not to feel a little bad for Art Howe. Or, at least, the version of Art Howe that Philip Seymour Hoffman put on screen. He’s grumpy. He’s stubborn. He looks like a guy who’s been told his favorite steakhouse is turning into a vegan juice bar.

But here’s the thing. The real Art Howe was actually a fitness fanatic. He was lean. He didn't sit around looking like a "perturbed Bassett Hound," which is how some critics described Hoffman's physical transformation for the role.

Honestly, the Philip Seymour Hoffman Moneyball performance is one of the most fascinating "villain" turns in sports cinema precisely because it’s so quiet. It isn't about mustache-twirling. It’s about a man who feels the world moving beneath his feet and refuses to look down.

The "Character Assassination" Controversy

When the movie dropped in 2011, Art Howe didn't just dislike it. He was livid. He called the portrayal "character assassination."

Imagine spending seven years building a reputation, leading a team to 100-win seasons, and then seeing an Oscar winner play you as a petty, overweight obstructionist who only cares about his contract extension. That’s gotta sting. Howe told SiriusXM that the filmmakers never even called him. Not once.

They didn't want his "slant." They wanted a foil for Brad Pitt’s Billy Beane.

In the film, Hoffman’s Howe is the ultimate "old guard" guy. He refuses to play Scott Hatteberg at first base. He ignores the spreadsheets. He fights Beane in the hallway. In reality? The relationship was professional. Sure, there were disagreements, but the "naked antagonism" we see on screen was largely a Hollywood invention to make the math of sabermetrics feel like a life-or-death struggle.

Why Philip Seymour Hoffman Was Actually Perfect (Even If He Was Wrong)

Director Bennett Miller and Hoffman were old friends. They had worked together on Capote, the film that won Hoffman his Academy Award. When Miller brought him into Moneyball, he wasn't looking for a lookalike.

He was looking for weight. Emotional weight.

Hoffman had this uncanny ability to play "emasculated" better than anyone in history. In Moneyball, he plays Howe as a man who has been stripped of his authority. Every time Billy Beane (Pitt) walks into the clubhouse to tell him who to bench, you see Hoffman’s jaw set. You see the resentment in his eyes.

It’s a masterclass in stillness.

While Pitt is all kinetic energy—eating Twinkies, throwing chairs, talking a mile a minute—Hoffman is a statue. He’s the wall that the wave of progress is crashing against. Even if the real Art Howe was a nice, fit guy who got along with his boss, that wouldn't have made for a great movie.

Hollywood needs a "no" man. Hoffman was the best "no" man in the business.

The Contract Scene: Fact vs. Fiction

One of the tensest moments in the film involves Howe cornering Beane about his contract. He wants security. He’s worried about his job.

- The Movie: Howe is on a one-year deal and feels disrespected.

- The Reality: Art Howe was actually on a two-year contract through 2003.

- The Narrative: By making him a "lame duck" manager, the script creates a reason for his stubbornness. If he’s fighting for his career, his refusal to experiment with Beane’s "island of misfit toys" makes more sense to an audience.

Basically, they traded factual accuracy for emotional logic.

The Tragedy of the "Thankless Role"

Critics often call the Philip Seymour Hoffman Moneyball role "thankless." It’s easy to see why. He doesn't get the big speeches. He doesn't get the girl. He doesn't even get the satisfaction of being right.

But watch the scene where Beane trades Carlos Peña just to force Howe’s hand.

Hoffman doesn't scream. He doesn't even move. He just looks at Beane with a mixture of pity and exhaustion. In that moment, he isn't just a "bad guy." He’s a guy who loves the game of baseball and feels like the "math nerds" are murdering the soul of it.

It’s a nuanced take on a character that could have been a caricature.

What We Can Learn From the Portrayal

Even though the real players and coaches—like David Justice and Art Howe—have voiced their frustrations with how Moneyball "Hollywood-ed" their lives, the movie remains a classic. Why? Because it’s not actually a documentary about the 2002 Oakland A's.

It’s a movie about the pain of change.

If you’re looking for the "true" story, read the Michael Lewis book. Or better yet, look at the stats of the 2002 pitching staff (Zito, Hudson, and Mulder) who are barely mentioned in the film but were the real reason the team won.

But if you want to see a world-class actor embody the quiet desperation of a man being left behind by history, you watch Hoffman.

📖 Related: Addison Rae: Why the Internet Is Still Heavy on Hotties and High Fashion

Actionable Insights for Fans and Historians

If you want to reconcile the movie with the reality, here are a few things to keep in mind:

- Check the Physicality: Don't let the movie convince you Art Howe was out of shape. He was a professional athlete who kept himself in top condition.

- Acknowledge the Pitching: The movie makes it look like Scott Hatteberg won the season. In reality, the A's had three of the best starting pitchers in the league. Hoffman’s character would have known that.

- Separate the Actor from the Script: Art Howe himself eventually said he never held a grudge against Hoffman. He knew the actor was just "playing the part he was given."

Philip Seymour Hoffman died just a few years after Moneyball was released. It stands as one of his final, great supporting turns. He took a role that was designed to be a "bump in the road" for the protagonist and turned it into a haunting portrait of the Old Guard.

The film might have gotten Art Howe the man wrong, but it got the feeling of the era exactly right. Sometimes, the legend is more useful than the truth.

To truly understand the impact of the film, you have to look past the box score. Watch the way Hoffman occupies the dugout. He’s not just a manager; he’s a ghost of baseball’s past. And in a movie about the future, that’s exactly what was needed.