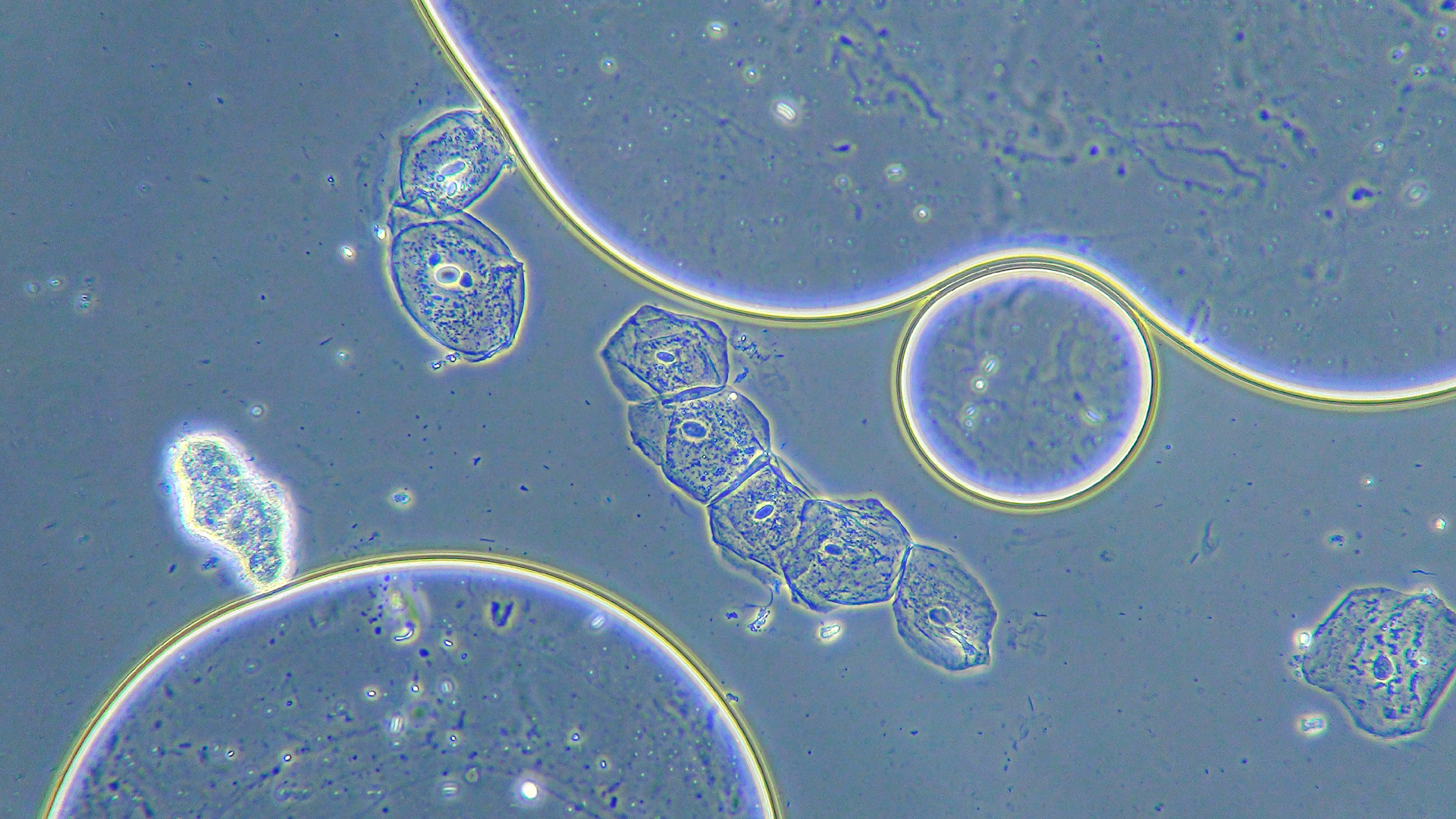

Ever looked at a cell through a standard brightfield microscope? It’s usually a ghost. Most living cells are transparent, watery blobs that let light pass right through them without a second thought. To see anything at all, you usually have to kill the cells and douse them in toxic stains like Methylene Blue or Eosin. But then, well, they're dead. This is exactly why phase contrast microscope pictures changed everything in biology. They let us see the invisible without murdering the specimen.

Frits Zernike, a Dutch physicist, figured this out in the 1930s. He realized that even if a cell doesn't absorb light (which would make it dark), it slows light down. That tiny delay is called a phase shift. Zernike found a way to turn those invisible delays into visible brightness changes. He won a Nobel Prize for it in 1953, and honestly, he deserved it.

The Physics of Shifting Light

Imagine light as a wave. When it hits a thick part of a cell—like the nucleus—it slows down just a tiny bit. To our eyes, this shift is totally invisible. We can see changes in amplitude (brightness) or frequency (color), but we are "phase blind."

🔗 Read more: Why the billionaire that wants to live forever is actually spending millions on your blood

Phase contrast microscopes use a clever trick involving an annular diaphragm and a phase plate. These components separate the light that hits the specimen from the light that doesn't. By shifting the phase of the background light, the microscope creates "interference." Think of it like two waves in the ocean crashing into each other. If they line up, they get bigger (bright). If they are out of sync, they cancel out (dark).

This is why phase contrast microscope pictures usually have that signature look: a glowing "halo" around the edges of the cells and a high-contrast internal structure. It’s not a digital filter. It’s actual physics happening in the light path.

Why the Halo Happens

You've probably noticed that bright white ring around objects in these photos. In the world of microscopy, we call this the "halo effect." It’s actually an optical artifact. It happens because some of the diffracted light from the specimen leaks into the phase ring of the objective lens.

Is it annoying? Sometimes. If you’re trying to measure the exact diameter of a bacterium, that halo can obscure the actual edge. But for general viewing, it actually helps the eye pick out the specimen against a messy background. It’s a trade-off. You get to see living, moving organelles, but you have to deal with a bit of "glow."

Comparing Imaging Techniques

If you’re shopping for a microscope or looking at data, you’ll see a few different styles of images.

Standard brightfield is what you used in high school. It’s great for stained tissue slices (like a biopsy), but for live bacteria? Forget it. You'll just see a bright white screen with maybe a few faint shadows.

Then there’s DIC (Differential Interference Contrast), often called Nomarski imaging. DIC produces images that look 3D, like they were carved out of gray stone. It’s gorgeous and lacks the "halo" of phase contrast, but it’s incredibly expensive. A decent DIC setup can cost three times more than a phase contrast one.

Phase contrast remains the "workhorse" because it’s relatively affordable and works with plastic petri dishes. DIC usually requires specialized glass bottoms because plastic messes with polarized light. If you're a grad student checking on your HeLa cell cultures at 2:00 AM, you're almost certainly looking at phase contrast microscope pictures.

Real-World Applications

Where do we actually see this in action?

- IVF Clinics: Doctors use phase contrast to check the health and motility of sperm cells and the quality of oocytes. Since you can’t exactly stain a human embryo and then expect it to grow, phase contrast is a literal life-saver.

- Wastewater Treatment: Operators look at "activated sludge." They need to see "ciliates" and "flagellates" swimming around to know if the bacteria are eating the waste properly.

- Cell Biology Research: Watching a cell divide (mitosis) in real-time. You can see the chromosomes lining up and pulling apart without using fluorescent dyes that might bleach or kill the cell.

The Problem with Thick Samples

Phase contrast is amazing for thin layers. If you have a single layer of cells on a slide, it’s crisp. But try looking at a thick piece of tissue or a large organism like a zebrafish larva? It becomes a blurry, glowing mess. This is because the light gets scattered too many times. For thick stuff, you’re better off with confocal microscopy or multiphoton imaging, though those require significantly more setup and money.

What Most People Get Wrong About These Photos

A common mistake is thinking that the darker areas in a phase contrast image are "denser." While often true, it’s actually about the refractive index. A small organelle with a very high refractive index might look darker or brighter than a larger, less dense one.

Also, people often confuse phase contrast with darkfield. In darkfield, the background is pitch black and the specimen is glowing white. In phase contrast microscope pictures, the background is usually a neutral gray. If your background is black, check your condenser alignment; you might be doing it wrong.

Getting the Best Image Possible

If you want to produce high-quality phase contrast microscope pictures, you can't just flip a switch. Alignment is everything.

- Center the Annulus: You have to use a "centering telescope" to make sure the ring of light is perfectly aligned with the phase plate inside the objective. If they’re off-center, your image will look "half-mooned" or lose contrast entirely.

- Clean Your Optics: Because this technique relies on subtle light shifts, a tiny fingerprint on the lens or dust on the slide will show up as a giant, distracting blob.

- Check Your Slide Thickness: Most phase objectives are "corrected" for a standard #1.5 coverslip (about 0.17mm thick). If you use a thick plastic plate with an objective meant for glass, the image will be "soft" and blurry.

Honestly, the biggest jump in quality usually comes from just turning down the light. Most people blast the brightness, which washes out the delicate phase structures. Keep it dim, adjust your gain on the camera, and let the physics do the work.

Practical Next Steps for Better Microscopy

If you are currently struggling with grainy or washed-out images, start by verifying your objective lens type. Look for the markings Ph1, Ph2, or Ph3 on the side of the lens barrel. You must match this to the corresponding setting on your condenser turret. Using a Ph2 objective with a Ph1 condenser setting will result in a standard brightfield image with zero contrast.

Next, invest in a dedicated microscopy camera rather than using a smartphone adapter if you need publication-quality files. While phones are great for a quick snap, the "computational photography" in modern iPhones often tries to "fix" the halo effect, which actually destroys the scientific data in the image. For true phase contrast microscope pictures, raw data is always better than an AI-enhanced photo.

Finally, ensure your specimen is as thin as possible. If you are viewing a culture, try to capture your images at 50-70% confluency. When cells overlap too much, the phase shifts interfere with each other, leading to a "muddy" image that is difficult to interpret or publish.