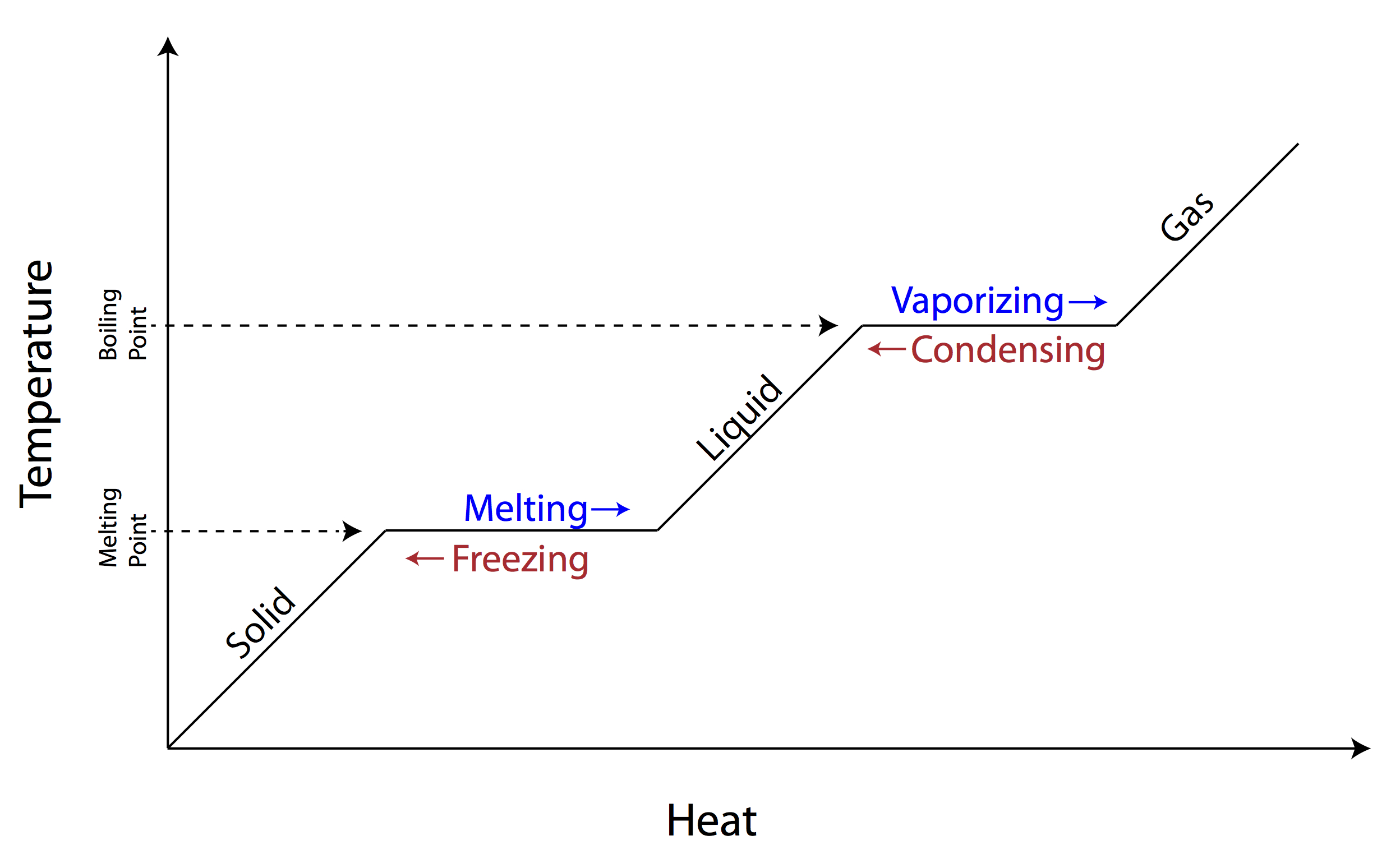

You’ve seen it in every high school chemistry textbook. It’s that jagged, stair-step line showing how ice turns into water and then into steam. Most people look at a phase change diagram and think, "Okay, heat goes in, temperature goes up." But that’s actually the boring part. The real magic happens where the line goes flat.

Temperature stays exactly the same. Even though you’re blasting it with a blowtorch.

Think about that. You’re adding massive amounts of energy to a pot of boiling water, yet the thermometer won't budge past 100°C (at sea level, anyway). It feels broken. It feels like physics is lying to you. Honestly, it’s one of those weird glitches in the universe that makes sense once you realize the energy isn't moving atoms faster anymore—it's literally ripping them apart from each other.

Why the Flat Lines on a Phase Change Diagram Matter

When you look at a heating curve, those horizontal plateaus are the "latent heat" zones. This isn't just academic fluff. If those plateaus didn't exist, your refrigerator wouldn't work, and your body wouldn't be able to cool itself down through sweat.

Basically, the energy is being used to overcome intermolecular forces. In a solid, atoms are locked in a tight, awkward embrace. To melt them, you have to break those bonds. On the phase change diagram, this is the heat of fusion. Once you hit the boiling point, you're dealing with the heat of vaporization.

Water is the weirdest example we have, mostly because of hydrogen bonding. Most substances get denser when they freeze. Water? It expands. That’s why pipes burst in the winter and why ice floats in your drink. If you look at a pressure-temperature phase diagram (the one that looks like a "Y"), water’s boundary line between solid and liquid actually leans to the left. Most substances lean right. That tiny tilt is the reason life exists on Earth; it means the bottom of the ocean stays liquid even if the top freezes.

The Triple Point and Other Weirdness

Ever heard of the triple point? It's the "Goldilocks" zone of pressure and temperature where a substance is simultaneously a solid, a liquid, and a gas. It’s not just a theoretical concept. Scientists use the triple point of water—specifically 273.16 K at a partial vapor pressure of 611.657 pascals—to calibrate ultra-precise thermometers.

🔗 Read more: How to Turn Your Location Off Without Breaking Your Phone

If you’ve ever seen a video of a liquid boiling and freezing at the same time in a vacuum chamber, you’re looking at the triple point in action. It looks like a glitchy video game.

Then there’s the critical point. Keep cranking up the heat and pressure, and eventually, the distinction between liquid and gas just... vanishes. You get a supercritical fluid. Industry loves these. Supercritical carbon dioxide is used to decaffeinate coffee beans because it has the effusive properties of a gas but the dissolving power of a liquid. It’s efficient. It’s clean. And it’s all mapped out on that phase change diagram.

Pressure Changes Everything

We usually think about phase changes in terms of temperature because that’s how we cook. But pressure is the secret variable.

If you’re a mountain climber at the top of Mt. Everest, your "boiling" water is barely hot enough to make a decent cup of tea. It boils at about 71°C because the atmospheric pressure is so low. The molecules can escape into the air much easier. Conversely, inside a pressure cooker, you’re forcing the water to stay liquid at temperatures way above 100°C, which is why your pot roast finishes in twenty minutes instead of four hours.

Real-World Engineering and the Phase Change Diagram

Engineers at companies like NASA or Boeing spend half their lives staring at these charts. When you're designing a heat shield for a spacecraft re-entering the atmosphere, you're looking at sublimation—where a solid turns directly into a gas.

- Dry ice (solid $CO_2$) is the classic example of sublimation at standard pressure.

- Freeze-drying your "astronaut food" or high-end coffee relies on this. They freeze the food, drop the pressure in a vacuum, and let the ice sublimate away without ever melting. This preserves the cellular structure of the food so it doesn't turn into mush.

Subcooling and Superheating: Breaking the Rules

Sometimes, the phase change diagram is more like a set of guidelines than actual laws.

Have you ever pulled a bottle of purified water out of a very cold freezer, and it looks liquid, but then you tap it and it instantly turns to ice? That’s subcooling. The water is below its freezing point, but the molecules haven't found a "seed" (like a speck of dust or a vibration) to start the crystallization process.

The same thing happens in a microwave with superheated water. You can get water way past 100°C without it boiling. Then, the moment you drop a tea bag or a spoon in, it explodes in a violent flash of steam. It's incredibly dangerous and a perfect example of why "ideal" diagrams don't always account for surface tension and purity.

Actionable Insights for Using Phase Data

If you're trying to apply this knowledge, whether for a chemistry exam or a DIY project, keep these practical realities in mind:

💡 You might also like: Mount Sinai Remote Access: How to Actually Log In Without Losing Your Mind

- Check your altitude. If you are baking or brewing at high elevations, your phase transitions happen earlier. Adjust your timings.

- Purity shifts the lines. Adding salt to water (freezing point depression) or sugar to a syrup (boiling point elevation) literally moves the lines on the phase change diagram. This is why we salt icy roads.

- Vacuum sealing matters. If you're trying to preserve food or dry out electronics, lowering the pressure is often more effective than raising the heat.

- Latent heat is a battery. Modern "phase change materials" (PCMs) are used in building insulation. They absorb heat during the day as they melt and release it at night as they solidify, keeping the indoor temperature stable without using electricity.

Stop thinking of phase changes as simple "on/off" switches. They are dynamic transitions governed by energy storage and environmental pressure. The next time you see steam rising from a pot, remember that the water is working incredibly hard just to stay at that temperature while it fights to break free.

To truly master this, your next step should be looking into "T-s diagrams" (Temperature-entropy) if you’re interested in engines, or "P-h diagrams" (Pressure-enthalpy) if you want to understand how air conditioning units actually move heat.