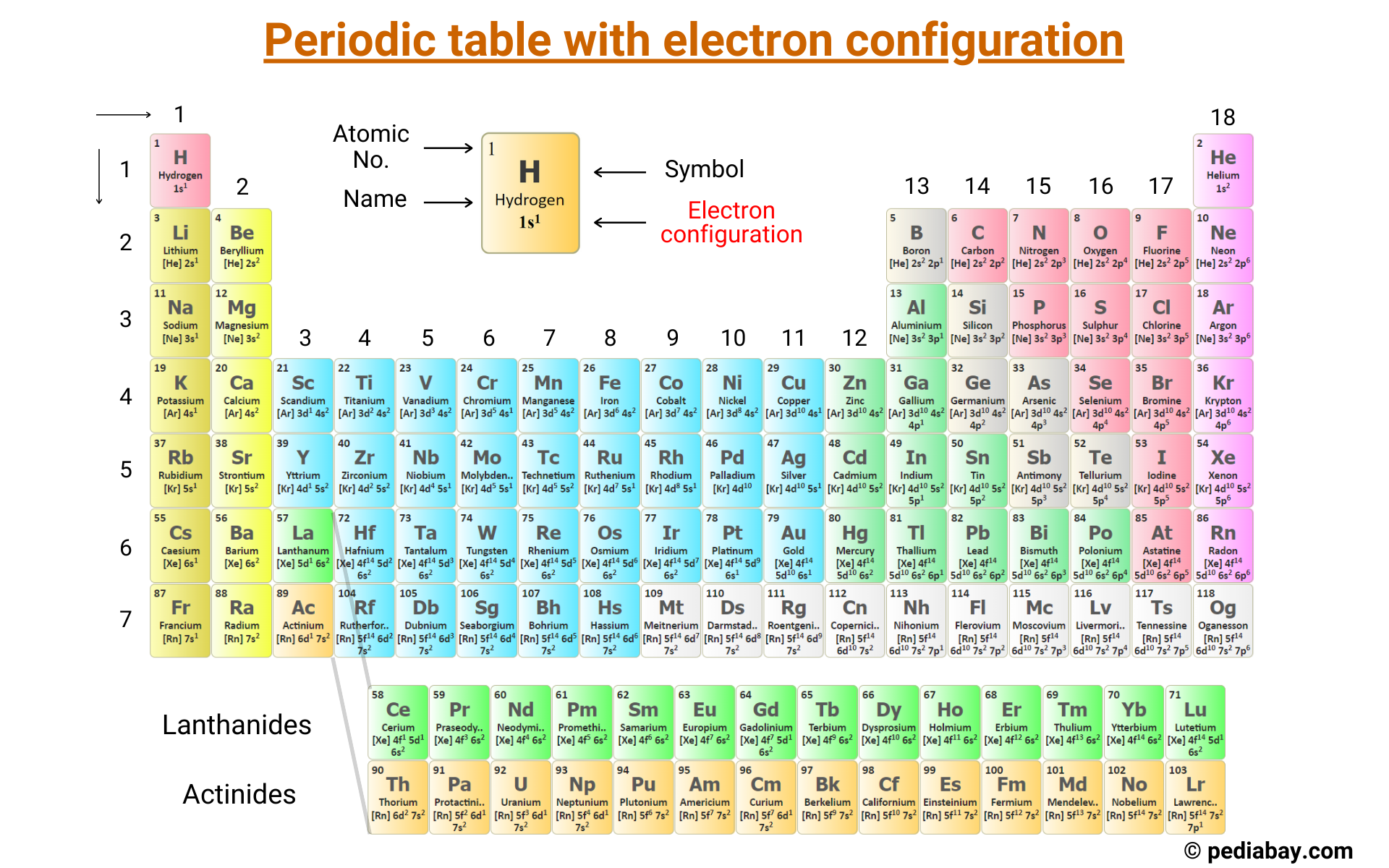

You probably remember staring at that giant, colorful chart on the wall of your high school chemistry class. It looked like a Tetris game gone wrong. Most people see the periodic table with electron configuration as a bunch of random boxes and numbers, but honestly, it’s more like a map of how the universe is glued together. It’s not just a list of elements. It’s a blueprint of where electrons "live."

Chemistry is messy. But the table is surprisingly organized once you realize it’s built on the behavior of subatomic particles.

The Real Logic Behind the Blocks

Ever wonder why the periodic table has those weird gaps at the top? It’s because of the $s$, $p$, $d$, and $f$ blocks. Electrons aren’t just floating around like flies. They follow strict rules, specifically the Pauli Exclusion Principle and Hund’s Rule.

Take Hydrogen. It’s the simplest thing in existence. One proton, one electron. Its configuration is $1s^1$. Simple, right? But as you move across to Helium ($1s^2$), you’ve filled that first "room." That’s why Helium is so chill—it doesn't want to react with anyone because its shell is full. It’s the introverted element of the gas world.

The periodic table with electron configuration is basically a giant apartment complex. The "periods" (the horizontal rows) tell you which floor you’re on. The "groups" (the vertical columns) tell you how many electrons are hanging out in the outermost hallway, also known as the valence shell. This is why Group 1 elements like Lithium and Sodium are so explosive when they touch water. They have one lonely electron in their outer shell and they are desperate to get rid of it.

Why the Transition Metals are the Weird Middle Children

If you look at the middle of the table—the $d$-block—things get a little funky. This is where we find Chromium and Copper. If you follow the standard Aufbau Principle, which says electrons fill the lowest energy levels first, you’d expect Chromium to end in $4s^2 3d^4$.

But nature loves symmetry.

Instead, Chromium "cheats" and takes one electron from the $s$ orbital to half-fill its $d$ orbital, resulting in $4s^1 3d^5$. Why? Because having a half-full subshell is more stable. It’s like how you might feel more balanced with a bag in each hand rather than two bags in one. This isn't just a textbook quirk; it’s the reason why these metals have the specific magnetic and conductive properties that power our modern world. Without this specific electron arrangement, your smartphone wouldn't have a vibration motor and your electric car's battery wouldn't hold a charge.

The Lanthanides and Actinides: The "Basement" Elements

Down at the very bottom, there are two rows that look like they were kicked out of the main party. These are the $f$-block elements. We call them the Lanthanides and Actinides.

For a long time, people thought these were just "rare earths" that didn't matter much. We were wrong. Neodymium ($[Xe] 4f^4 6s^2$) is the reason we have tiny, powerful magnets. High-tech manufacturing relies entirely on the periodic table with electron configuration to predict how these $f$-block elements will behave when they're shoved into alloys. These elements have electrons filling deep, inner shells, which shields them in a way that creates unique optical and magnetic signatures.

Common Misconceptions About Electron Shells

People often think electrons orbit the nucleus like planets around the sun. That’s the Bohr model. It’s easy to draw, but it’s mostly wrong.

In reality, we’re talking about orbitals, which are probability clouds. An electron in a $p$-orbital is moving in a figure-eight shape. In a $d$-orbital, it’s often a four-leaf clover shape. When we talk about the periodic table with electron configuration, we are actually mapping out these clouds of probability.

- The Octet Rule isn't a law. It’s more like a strong suggestion. Elements like Sulfur can actually "expand" their octet because they have access to $d$-orbitals, which lets them hold more than eight electrons.

- Energy levels overlap. This is the big one. The $4s$ orbital actually fills before the $3d$ orbital. It sounds counterintuitive, but $4s$ is slightly lower in energy.

- Valence electrons are the only ones that "talk." The inner electrons (core electrons) are basically dead weight in a chemical reaction. They just shield the nucleus.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you’re trying to master this, stop memorizing and start looking for the patterns.

- Look at the row number. That's your principal quantum number ($n$).

- Look at the block ($s, p, d, f$).

- Count across the block to find the exponent.

For example, if you want the configuration for Carbon: It’s in the second row, in the $p$-block, and it’s the second element in that block. So, you start from the beginning: $1s^2$ (Helium's spot), then $2s^2$ (Beryllium's spot), then $2p^2$ (Carbon's spot). Put it together: $1s^2 2s^2 2p^2$.

📖 Related: Why Variety Die and Stamping Processes Are Quietly Carrying Modern Manufacturing

The Future of the Table

We are currently at element 118, Oganesson. Its electron configuration is $[Rn] 5f^{14} 6d^{10} 7s^2 7p^6$. It’s the end of the current table. Scientists are already trying to synthesize elements 119 and 120, which would start a brand new row—the 8th period.

There’s a lot of debate about whether the periodic table with electron configuration will even hold up at those extreme levels. When you get atoms that big, the electrons start moving at relativistic speeds (a significant fraction of the speed of light). This changes their mass and how they behave. Gold is yellow and Mercury is a liquid at room temperature precisely because of these relativistic effects on their electrons. If the table keeps growing, the "rules" we learned in school might start to break.

Practical Steps for Mastery

To really get comfortable with this, you should try the "Noble Gas Shorthand" immediately. Nobody wants to write out the full configuration for Lead ($Pb$). It’s exhausting. Instead, find the Noble Gas in the row above it (Xenon) and just write $[Xe]$ followed by the remaining electrons: $[Xe] 4f^{14} 5d^{10} 6s^2 6p^2$.

- Practice with Ions: Remember that when an atom becomes an ion, it loses or gains electrons to look like a Noble Gas. A Sodium ion ($Na^+$) has the same configuration as Neon.

- Visualize the Orbitals: Use 3D simulators online to see the shapes. It’s much easier to understand why the $p$-block has six elements when you see the three different $p$-orbitals ($x, y, z$) that each hold two electrons.

- Identify the Exceptions: Focus on Copper and Chromium. These are the "trick" questions on every exam and the keys to understanding real-world metallurgy.

The periodic table with electron configuration isn't just for scientists in lab coats. It's the dictionary for the language of matter. Once you can read it, you can understand why things burn, why metals conduct, and why some gases are deadly while others keep us alive.

Go find a high-resolution version of the table that specifically labels the subshells. Spend ten minutes tracing the path from Hydrogen to Lawrencium. You’ll start to see the rhythm of the universe in a way that simple memorization never allows.