Ever looked at the periodic table and felt like it was lying to you? Most people assume that as you add more protons, neutrons, and electrons to an atom, the thing just naturally gets bigger. It makes sense, right? If you put more stuff in a bag, the bag expands. But chemistry is weird. In the world of the periodic table of elements atomic size, more "stuff" often leads to a smaller footprint.

It’s counterintuitive.

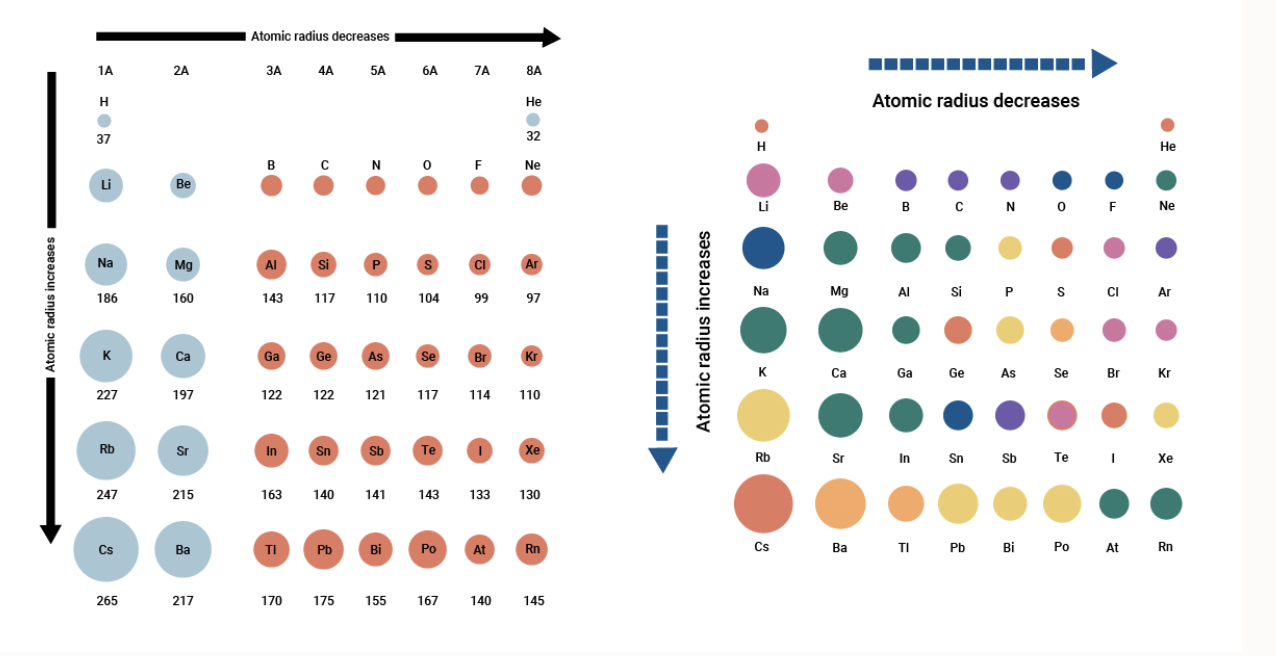

If you move from left to right across a single row—what scientists call a period—you’re literally adding mass. You’re adding protons to the nucleus. You’re adding electrons to the shells. Yet, the atom shrinks. This isn’t a mistake or a rounding error. It’s the result of a high-stakes tug-of-war between the center of the atom and its outer edges.

Understanding this isn't just for passing a chemistry quiz. It’s the reason why your smartphone battery works and why certain metals are soft enough to cut with a butter knife while others are used to build skyscrapers.

The Shrinking Act: Periodic Table of Elements Atomic Size Explained

The main driver here is something called Effective Nuclear Charge ($Z_{eff}$). Think of the nucleus like a giant magnet and the electrons like little metal bearings. As you move across a row, you keep adding "magnet strength" (protons) to the center. However, you aren't adding new shells for the electrons to sit in. They stay roughly the same distance away.

Because the "magnet" in the middle is getting stronger but the electrons aren't moving further out, the nucleus pulls those electrons in tighter. It’s a literal squeeze. By the time you get to the right side of the table, like Fluorine or Neon, the atom is significantly more compact than the Lithium or Beryllium you started with on the left.

It’s a bit like a crowded elevator.

If everyone stays on the same floor but the gravity suddenly doubles, everyone is going to be hunched closer to the ground. That’s basically what’s happening to the electron cloud. This trend is one of the most reliable "rules" in science, though there are always those pesky transition metals that like to break the mold.

Why Going Downward Changes Everything

Now, if you look at the columns—the groups—the story flips. This is where the "bag" analogy actually works. As you go down a column, you’re adding entire new layers of electrons. Chemists call these principal energy levels.

Imagine putting on five winter coats. You’re going to look a lot bigger than you did in a t-shirt. Even though the nucleus is getting way stronger as you go down from Hydrogen to Cesium or Francium, the "shielding effect" takes over. All those inner layers of electrons act like a physical barrier, blocking the pull of the nucleus. The outer electrons are just too far away to feel the tug.

So, they wander out. They take up space.

This creates a clear diagonal trend: the atoms in the bottom-left corner of the table, like Francium, are the absolute giants. The atoms in the top-right, like Helium, are the tiny specks. If you compare a Cesium atom to a Helium atom, it’s like comparing a beach ball to a marble.

The Lanthanide Contraction: A Weird Exception

Sometimes nature gets tired of following its own rules. There’s this phenomenon called the Lanthanide Contraction. It happens with the heavy elements—those rows that usually sit at the bottom of the chart.

Because the "f-orbitals" are really bad at shielding the nucleus, the pull of the center is way stronger than it should be. The result? Elements in the sixth period end up being almost the same size as the elements directly above them in the fifth period. This is why Hafnium and Zirconium are like twins; they have nearly identical atomic radii, which makes them incredibly difficult to separate in industrial processes.

Real-World Impact: Why Size Matters

You might wonder why anyone cares about a few picometers of space. But atomic size dictates reactivity.

👉 See also: Data Strike Christmas 2024: What Most People Get Wrong About the Digital Blackout

Take Cesium. Because it’s so huge, its outermost electron is barely hanging on. The nucleus is so far away that it has almost no grip on that electron. This makes Cesium violently reactive. Drop it in water, and it doesn't just fizz; it explodes.

On the flip side, look at Fluorine. It’s tiny. Its nucleus is right there, practically touching the outer edge. It is desperate to grab another electron to fill its shell. This "greed" for electrons, driven by its small size, makes it the most reactive non-metal on the planet.

- Batteries: Lithium is used in batteries partly because it’s small and light, allowing ions to move quickly.

- Catalysts: In your car's catalytic converter, the size of Platinum or Palladium atoms determines how well they can grab onto exhaust gases.

- Medicine: Doctors use certain large-atom isotopes for imaging because their size influences how they move through the human body.

Measuring the Unmeasurable

How do we even know how big an atom is? It’s not like we can use a ruler. Atoms don't have hard edges; they’re more like fuzzy clouds of probability.

Scientists usually measure the distance between the nuclei of two identical atoms that are bonded together. They take that distance and cut it in half. That’s the atomic radius. But even that changes depending on whether the atom is in a metallic bond, a covalent bond, or just bouncing around as a noble gas. It’s a bit of an estimate, but it’s an incredibly precise one.

The Heavy Metal Problem

As we get into the super-heavy elements—the ones humans have to create in particle accelerators—the periodic table of elements atomic size rules start to get even wonkier.

Relativistic effects start to kick in.

In these massive atoms, the inner electrons are moving so fast (significant fractions of the speed of light) that they actually gain mass. This extra mass makes the electrons pull closer to the nucleus, shrinking the atom more than the standard trends would predict. Elements like Copernicium or Oganesson might not behave like the rest of their "family" simply because their electrons are moving too fast to care about the usual rules of chemistry.

Practical Steps for Mastering Atomic Trends

If you're trying to use this information for a project, a test, or just to understand materials science better, don't just memorize the chart. Understand the "why."

- Check the Shells first. If you’re comparing atoms in different rows, the one further down the table is almost always bigger because it has more layers.

- Check the Protons second. If they are in the same row, count the protons. More protons mean a stronger "magnet" and a smaller atom.

- Watch for Ions. Remember that an atom changes size instantly if it loses or gains an electron. A positive ion (cation) is always smaller than its neutral version because it lost a whole "coat." A negative ion (anion) is always bigger because the electrons start pushing each other away.

- Visualize the Diagonal. Draw a line from the top-right (Helium) to the bottom-left (Francium). Size increases as you move toward Francium.

Basically, size in the atomic world is a balance of power. It’s a fight between the number of layers you’re wearing and how hard the center of your being is trying to pull those layers inward.

To really see this in action, look up the "Atomic Radius vs. Atomic Number" graph. You’ll see a beautiful, repeating "sawtooth" pattern. Each peak is an Alkali metal (the giants) and each valley is a Noble gas (the tiny ones). It’s one of the most visual proofs we have that the universe is organized by very specific, albeit slightly weird, mathematical laws.

Next Steps:

To deepen your understanding, compare the atomic radii of the Group 1 elements against Group 17. Note the massive disparity. Then, investigate how "ionic radius" differs from atomic radius, as this shift is what actually drives chemical bonding in salts and minerals. Keep a periodic table handy and try to predict which element is larger between Phosphorus and Germanium—it’s harder than it looks because you have to balance both the row and the column shifts.