You're staring at a chemistry problem and the numbers just aren't clicking. It's frustrating. You know sodium is plus one, and you’re pretty sure oxygen is minus two, but then you hit the middle of the board—the transition metals—and everything goes sideways. Why does iron get to have two different personalities? Why does lead act like a rebel? Periodic table ionic charges aren't just random numbers assigned by some bored scientist in the 1800s; they are the literal "handshakes" of the universe.

If you don't get these charges right, you can't balance an equation. If you can't balance an equation, you can't predict a reaction. Basically, you're flying blind.

The Octet Rule is Kind of a Lie (But a Useful One)

We're all taught the Octet Rule in high school. It’s the idea that every atom wants eight valence electrons to be "happy" and stable, like the noble gases in Group 18. While that’s a great starting point, it’s honestly a bit of a simplification that trips people up later.

Atoms don't have "feelings." They have energy states. An atom will gain or lose electrons—creating those periodic table ionic charges—simply because it's energetically cheaper to do so.

Take Fluorine. It has seven electrons in its outer shell. It is desperately "hungry" for one more. Getting that eighth electron releases a massive amount of energy, which is why Fluorine is so reactive it can literally set water on fire. On the flip side, Lithium has one lonely electron in its outer shell. It’s much easier for Lithium to just toss that one electron away than to try and scavenge seven more. This is why Group 1 elements are always +1. They are the minimalists of the chemical world.

Where the Patterns Actually Work

For the representative elements—the tall columns on the left and right—the charges are actually super predictable. You've probably seen the shortcut: Group 1 is +1, Group 2 is +2. Then you skip the middle "valley" and hit Group 13, which is +3.

🔗 Read more: I Forgot My iPhone Passcode: How to Unlock iPhone Screen Lock Without Losing Your Mind

But wait.

The pattern breaks as you move down. In Group 14 (the Carbon group), things get weird. Carbon usually shares electrons (covalent bonding) rather than forming ions. But then you look at Lead (Pb) at the bottom. Lead can be +2 or +4. This is due to something called the Inert Pair Effect. Basically, those s-orbital electrons are buried so deep that they sometimes refuse to join the party, leaving only the p-electrons to do the work.

- Group 15 (Nitrogen group) usually takes 3 electrons to hit that magic number eight, giving them a -3 charge.

- Group 16 (Oxygen/Chalcogens) wants 2, so they're -2.

- Group 17 (Halogens) are the most aggressive electron-stealers, consistently -1.

The Chaos of the Transition Metals

The d-block. The "middle" of the table. This is where most students lose their minds.

Unlike the representative elements, transition metals are like the "multitaskers" of chemistry. They can lose different numbers of electrons depending on who they are reacting with. Iron (Fe) is the classic example. It can be $Fe^{2+}$ (Ferrous) or $Fe^{3+}$ (Ferric).

Why? Because of the d-orbitals.

💡 You might also like: 20 Divided by 21: Why This Decimal Is Weirder Than You Think

In these elements, the energy level of the 4s electrons and the 3d electrons is incredibly close. An atom might lose its 4s electrons first, but then it realizes that by losing one more from the 3d shell, it can reach a more stable, half-filled d-orbital state. It’s all about reaching the lowest possible energy.

Chromium is even weirder. It can be +2, +3, or even +6. When you see Chromium-6 (hexavalent chromium), you should probably run—it’s the stuff from the Erin Brockovich story. It’s highly oxidative and toxic because it’s "missing" six electrons and will do anything to get them back, including ripping them out of your DNA.

Real Talk: The Electronegativity Factor

You can't talk about periodic table ionic charges without mentioning electronegativity. This is the "tug-of-war" strength of an atom. Linus Pauling, a two-time Nobel laureate, developed the scale we use today.

If two atoms have a massive difference in electronegativity, the stronger one just steals the electron. Boom. Ionic bond. If they are close, they share. This is why the bottom-left of the table (Francium) and the top-right (Fluorine) are the ultimate opposites. Francium is the most "generous" (it has the lowest electronegativity) and Fluorine is the most "selfish."

Common Mistakes You’re Probably Making

- Mixing up Charge and Oxidation State: While they are often the same number, they aren't the same concept. Charge is a physical property of an ion. Oxidation state is more like a "bookkeeping" method chemists use to track electrons during reactions.

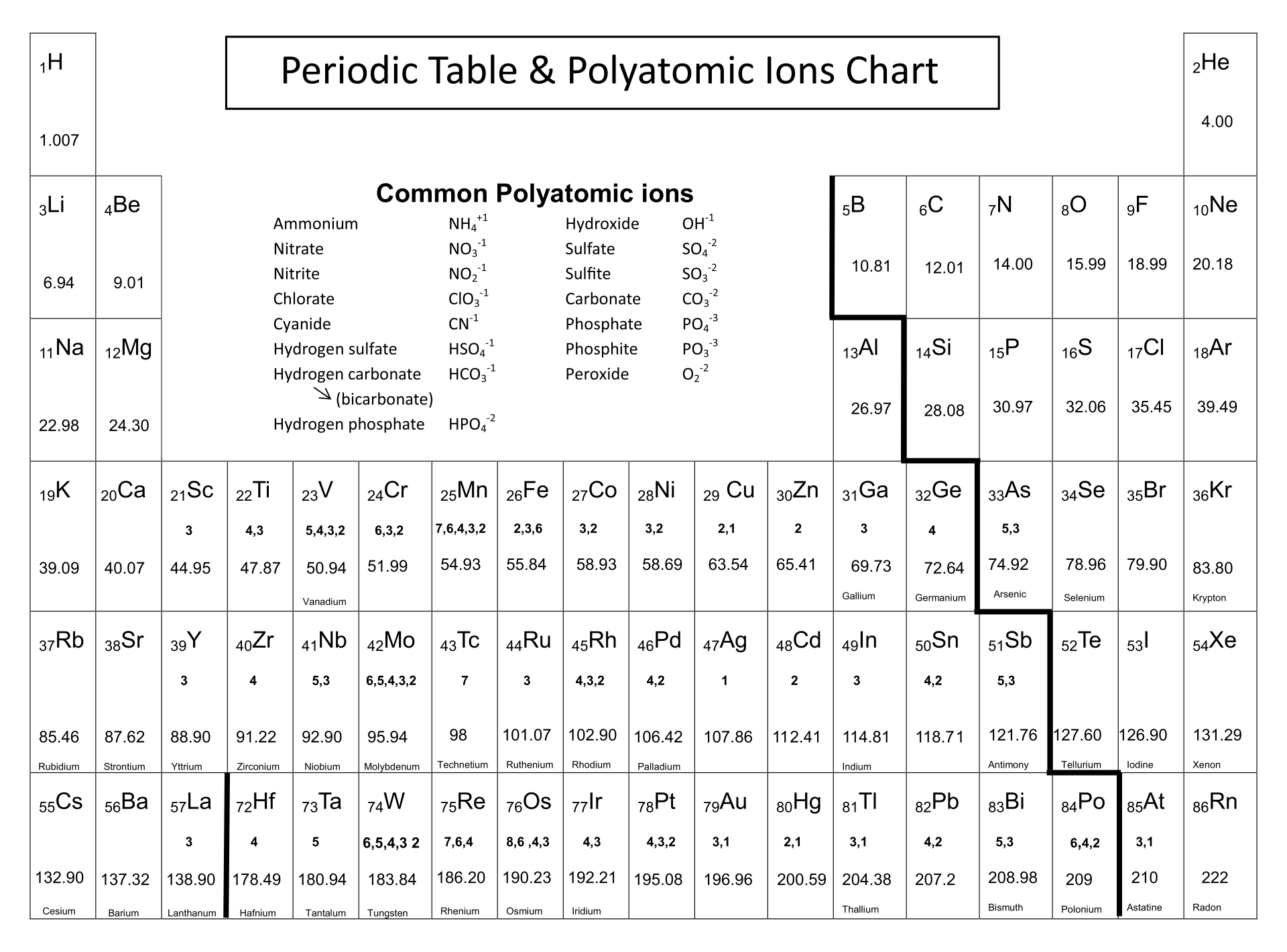

- Forgetting Polyatomic Ions: Not every ion is a single atom. Sulfate ($SO_4^{2-}$) or Ammonium ($NH_4^+$) act as a single unit with a locked-in charge. If you try to break these apart based on the periodic table alone, you're going to have a bad time.

- Ignoring the Roman Numerals: If you see "Copper(II) Chloride," that (II) is the charge. People often try to look at the periodic table to find Copper's charge, but transition metals tell you exactly what they are doing in their name.

How to Use This Knowledge Right Now

Stop trying to memorize every single element. It’s a waste of brain space. Instead, memorize the "anchor" points.

📖 Related: When Can I Pre Order iPhone 16 Pro Max: What Most People Get Wrong

Know your Halogens are -1. Know your Alkali metals are +1. Use those as your fixed points to solve for the "unknowns" in a molecule. If you have $FeCl_3$, and you know each Chlorine is -1 (which it is, because it's in Group 17), then the Iron must be +3 to make the molecule neutral. It's just simple algebra disguised as science.

Look at your periodic table not as a chart of names, but as a map of energy. The further an atom is from the edges (the Noble Gases), the more "unstable" and "charged" it wants to become.

Actionable Steps for Mastering Charges

- Print a blank table: Try to fill in the charges of the representative groups from memory. Do it until it takes you less than thirty seconds.

- The "Cross-Over" Trick: When writing formulas like Aluminum Oxide, take the charge of Aluminum (+3) and make it the subscript for Oxygen. Take the charge of Oxygen (-2) and make it the subscript for Aluminum. You get $Al_2O_3$. It works 90% of the time.

- Check the d-block exceptions: Silver (Ag) is almost always +1. Zinc (Zn) is almost always +2. Cadmium (Cd) is +2. These are the "hidden" constants in the middle of the chaos.

- Download a Chem-App: Use something like "Polyatomic" or a high-end Periodic Table app that shows "common oxidation states." Seeing the list of possibilities for Manganese (it has like five!) helps you realize that it’s okay to be confused—Manganese is confusing.

Chemistry is just a game of keeping track of where the tiny negative particles go. Once you realize the periodic table ionic charges are just the rules of that game, the whole subject starts to feel a lot less like magic and a lot more like logic.

Next Steps for Mastery:

Focus your next study session specifically on Polyatomic Ions. Since these groups of atoms carry their own charges ($PO_4^{3-}$, $NO_3^-$), they are the missing link between understanding simple periodic charges and actually being able to name complex chemical compounds. Grab a flashcard app and drill the top 10 polyatomics—it will make the transition metals feel much less intimidating.