Numbers don't lie, but people sure do. If you've spent more than five minutes on social media lately, you've probably seen a dozen different charts claiming to explain the percentage of crime by race in america. Most of them are cherry-picked. Some are just flat-out wrong. To really get what’s happening, you have to look at the raw data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program, and honestly, the reality is a lot more layered than a thirty-second soundbite suggests.

Crime isn't a monolith.

When we talk about "crime," we’re usually mashing together everything from shoplifting and public intoxication to aggravated assault and homicide. The demographic breakdown changes wildly depending on which category you're looking at. In 2023, the FBI’s expanded data showed that White individuals accounted for about 67% of all arrests in the United States. Black or African American individuals accounted for roughly 26%. But those broad strokes hide the details that actually matter for public policy and community safety.

Breaking Down the Numbers by Category

If you look at the 2022 and 2023 FBI arrest tables—which are the most recent "complete" sets we have since the NIBRS transition—the percentage of crime by race in america starts to show specific trends.

For violent crimes like murder and non-negligent manslaughter, the numbers are often what spark the most heated debates. In recent years, Black Americans—who make up roughly 13% to 14% of the U.S. population—have accounted for about 50% of homicide arrests. White Americans make up about 45% to 48% of those same arrests. These are stark figures. You can't just ignore them. However, when you pivot to different types of crime, the leaderboard flips.

Take "Driving Under the Influence" (DUI). White individuals make up the vast majority of these arrests, often exceeding 80% in various reporting years. Liquor law violations and arson also trend heavily toward the White demographic.

It's kinda fascinating how we categorize "danger." We tend to fixate on the crimes that happen on a street corner but ignore the ones that happen behind a steering wheel, even though both can be equally lethal.

Property Crime and Theft

Property crime is a different beast entirely. We’re talking about burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft. In this arena, the gap narrows. White individuals typically represent about 55-60% of arrests for property crimes, while Black individuals represent around 30-35%.

🔗 Read more: How Did Black Men Vote in 2024: What Really Happened at the Polls

What’s often missed in the percentage of crime by race in america conversation is the Asian and Native American data. Asian Americans consistently show the lowest arrest rates across almost every single category, often hovering around 1% to 2% of total arrests, despite making up roughly 6-7% of the population. Native Americans and Alaska Natives, conversely, face disproportionately high arrest rates in specific rural jurisdictions, particularly regarding alcohol-related offenses, though their national percentage remains low due to their smaller total population.

The Poverty Variable Nobody Likes to Mention

You can’t talk about these percentages without talking about money. Or the lack of it.

Most criminologists, like those at the Brennan Center for Justice, argue that race is often a proxy for socioeconomic status. If you take two neighborhoods with the exact same poverty rate, same unemployment rate, and same number of single-parent households—one Black and one White—the crime rates tend to look remarkably similar. The problem is that in America, poverty is not distributed evenly.

Because of historical factors—redlining, the GI Bill's uneven application, and the "war on drugs"—poverty is more concentrated in Black communities. When you concentrate poverty, you concentrate crime. It’s a pressure cooker.

Think about it this way: a kid in an affluent suburb who gets caught with a bag of weed might get a "don't do it again" from a cop who knows his dad. A kid in a high-crime, low-income urban area gets a pair of handcuffs and a permanent record. That record then makes it impossible to get a job, which leads to... well, more crime. It’s a feedback loop that inflates the arrest percentages for certain groups while masking them for others.

Why the FBI Data Is (Kinda) Incomplete

Here’s a dirty little secret about the percentage of crime by race in america: the data is only as good as the police departments reporting it.

The FBI doesn’t just snap its fingers and get these numbers. Local precincts have to volunteer them. In 2021, when the FBI switched to a new reporting system called NIBRS, a huge chunk of the country—including massive departments like the LAPD and the NYPD—didn’t report their data in time. This created a massive "data gap."

💡 You might also like: Great Barrington MA Tornado: What Really Happened That Memorial Day

While participation has bounced back significantly in 2024, we still have "blind spots."

Furthermore, "arrest data" is not "crime data." An arrest means a police officer decided there was probable cause. It doesn't always mean a crime was committed, and it certainly doesn't account for crimes that go unsolved. If police spend 90% of their time patrolling one specific neighborhood, they’re going to find more crime there. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. This doesn't mean the crimes aren't happening, but it means the percentage of arrests might not perfectly mirror the percentage of people actually breaking the law.

The Hispanic/Latino Data Problem

Another thing that muddies the water? The way we track Hispanic identity.

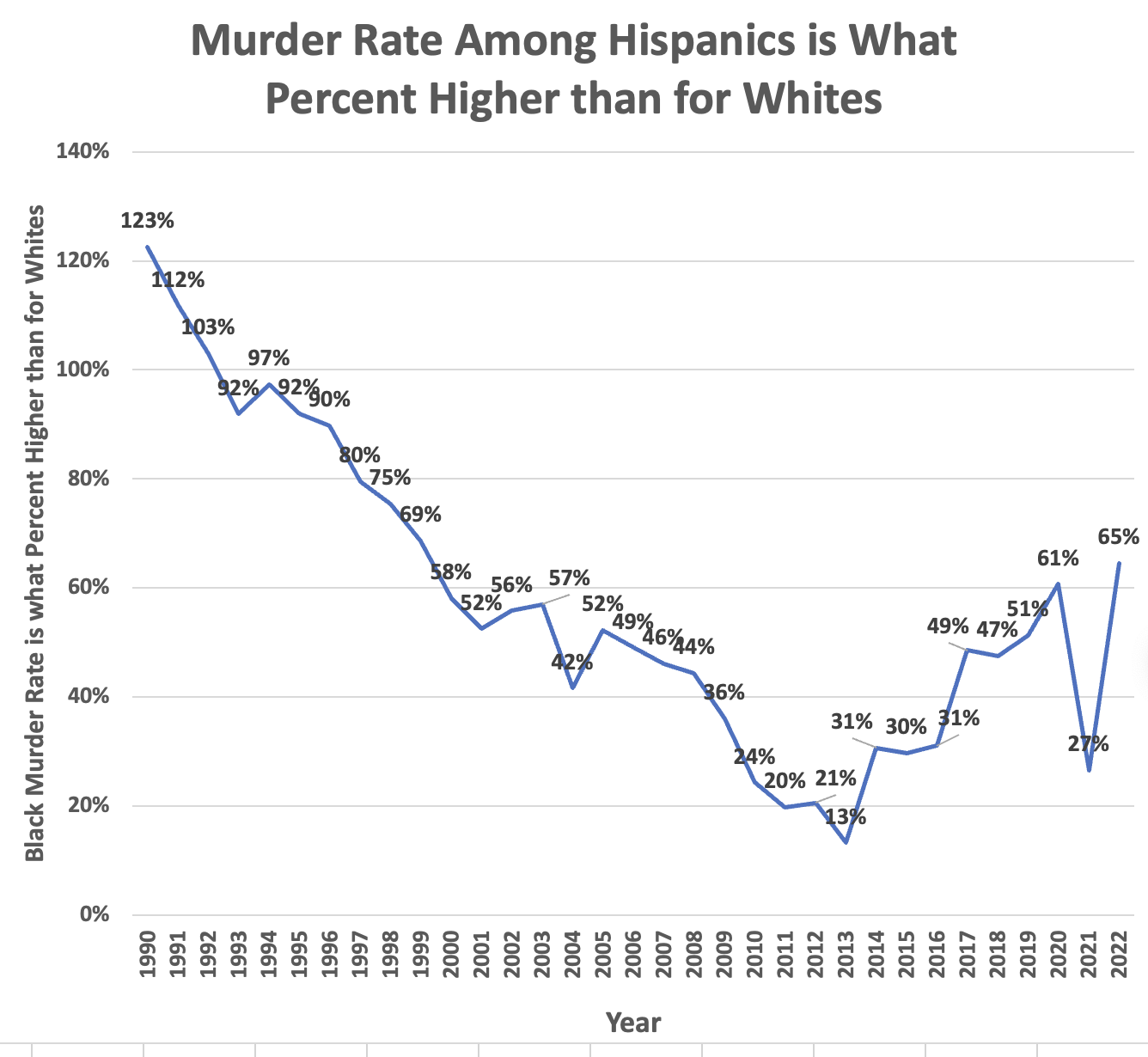

In many older FBI datasets, "Hispanic" was treated as an ethnicity, not a race. This meant a person could be "White and Hispanic" or "Black and Hispanic." In many police reports, Hispanic suspects were simply checked off as "White." This significantly inflates the White crime percentage in states like Texas, California, and Arizona. The DOJ has been trying to fix this by mandating better reporting, but the historical data is a mess because of it. If you're looking at a chart from 2015, those "White" crime numbers almost certainly include a massive number of Hispanic individuals.

Victimization: The Other Side of the Coin

We usually focus on who is doing the crime, but the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) tells us who is suffering from it.

Crime is overwhelmingly intraracial.

This is a point that gets lost in the political shouting matches. White people are most likely to be victimized by White people. Black people are most likely to be victimized by Black people. For example, in 2022, roughly 80% of White homicide victims were killed by White offenders, and about 90% of Black homicide victims were killed by Black offenders.

📖 Related: Election Where to Watch: How to Find Real-Time Results Without the Chaos

Violence is usually local and personal. It’s about proximity. You are most likely to be harmed by someone you know or someone who lives near you. Since America remains fairly residentially segregated, the "race" of crime usually follows the "race" of the neighborhood.

What This Means for 2026 and Beyond

Looking at the percentage of crime by race in america shouldn't be about winning an argument. It should be about figuring out where to put resources.

If we see a spike in a specific type of crime in a specific demographic, the answer usually isn't "that group is inherently more criminal." That's a lazy take. The real answer is usually found in looking at the closing of local factories, the rise of a new synthetic opioid, or the lack of after-school programs.

For instance, the recent surge in "Kia Boyz" style car thefts—largely perpetrated by younger, urban teens—has skewed property crime stats in the last couple of years. Is that a "race" issue? Or is it a "viral TikTok trend meeting a lack of social supervision" issue?

Moving Toward Solutions

Understanding these statistics requires a bit of intellectual honesty. You have to be able to acknowledge that some groups are overrepresented in violent crime arrests while also acknowledging that the legal system doesn't always treat every group the same. Both things can be true at once.

If you're looking to actually use this information for anything productive, here are the steps to take:

- Audit Local Data: Don't just look at national FBI stats. Go to your city’s "Open Data" portal. See which precincts are making arrests and for what. Often, a city's entire crime spike is driven by just two or three blocks.

- Support Evidence-Based Intervention: Programs like "Operation Ceasefire" or "Cure Violence" treat crime like a public health issue. They go after the "social contagion" of violence without relying solely on mass arrests.

- Look at the "Clearance Rate": This is the percentage of crimes that police actually solve. In many high-crime areas, the clearance rate for murders is below 40%. When people feel the state can't protect them or catch offenders, they are more likely to take the law into their own hands, which keeps the cycle of violence—and the arrest stats—climbing.

- Contextualize the "Why": If you see a stat that looks shocking, ask about the age demographic. Crime is a young man’s game. Most people "age out" of crime by their 30s. Areas with a younger "bubble" in the population will naturally have higher crime rates regardless of race.

The percentage of crime by race in america is a snapshot of a moment in time, influenced by geography, economy, and police policy. It's a starting point for a conversation, not the final word.

To get the most accurate picture, you should regularly check the FBI’s Crime Data Explorer and the Bureau of Justice Statistics' annual reports. They update these figures annually, and the trends often tell a more important story than a single year's data. For 2026, the focus is shifting heavily toward how AI-driven policing and tech-based theft are altering these traditional demographic lines, which will likely change the percentages we see in the coming decade.