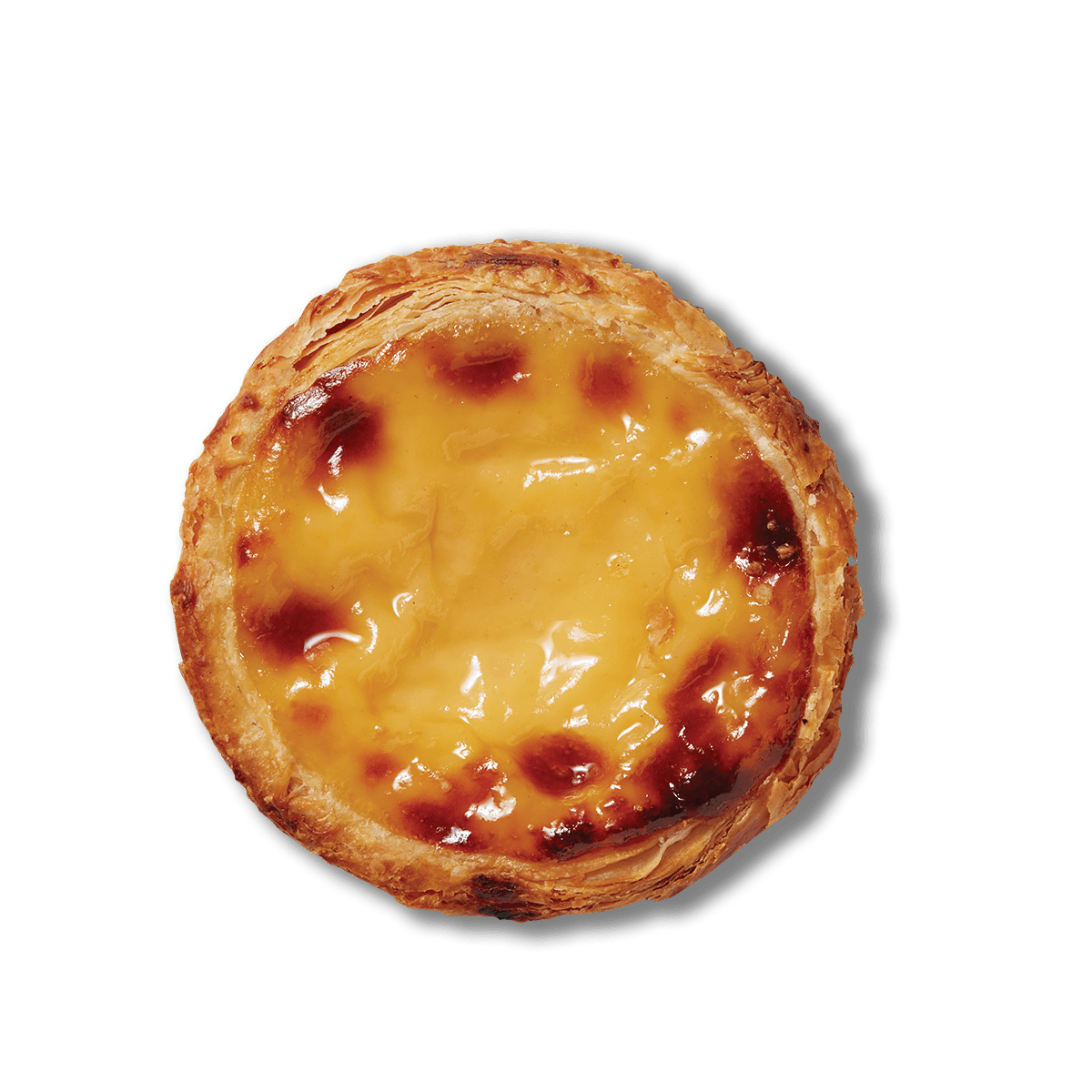

It’s thick. It’s yellow. It tastes exactly like a custard tart that’s been liquefied and spiked with a bit of fire. If you’ve spent any time in a Lisbon souvenir shop or scrolled through a "What to eat in Portugal" TikTok feed lately, you’ve definitely seen those little bottles of pastel de nata liqueur. People usually buy them because the bottle looks cute or they want to take a piece of their vacation home, but once they get it into their kitchen, they realize they have absolutely no idea what to do with it besides taking a room-temperature shot that feels a bit like drinking boozy pancake batter.

Honestly? Most people are drinking it wrong.

The Weird History of a Tart in a Bottle

Portuguese custard tarts, or pastéis de nata, have been around since before the 18th century, thanks to the monks at the Jerónimos Monastery in Belém. They used egg whites to starch their clothes, which left them with a massive surplus of yolks. Naturally, they made sweets. But the liqueur version? That’s a much newer phenomenon. It’s not some ancient monastic secret. It’s a clever bit of modern distilling aimed at capturing the vanilla, cinnamon, and burnt-sugar essence of the world's most famous pastry. Brands like Licor 35 and Casal dos Jordões have basically cornered the market by figuring out how to emulsify dairy (or dairy-adjacent flavors) with alcohol without it curdling on the shelf.

It's a technical feat. Getting that specific "crust" flavor—that hint of toasted puff pastry—into a liquid is hard.

Most versions sit around 14.5% to 15% ABV. That’s lower than a heavy fortified wine like Port, but higher than your average beer. It’s meant to be a digestif, something you sip after a heavy meal of bacalhau or frango assado. But because it’s so sweet, it’s polarizing. Some people think it’s a masterpiece of confectionery science; others find it cloying.

What is actually inside the bottle?

You’d think it’s just melted tarts, but the reality is more about chemistry. Most brands use a base of neutral spirit or sometimes a grape-based brandy. Then comes the cream base. To get the flavor right, they use a heavy hand of lemon zest and cinnamon, because that’s what separates a Portuguese custard tart from a standard French flan.

The lemon provides the high notes. The cinnamon provides the warmth.

If you look at the back of a bottle of Licor 35—probably the most recognizable brand with its bright yellow label—you won't find a list of "crushed pastries." You’ll find milk derivatives, sugar, and flavorings. It’s a processed product, sure, but so is Baileys, and we don't hold that against the Irish. The magic is in the proportions.

Why You Shouldn't Just "Shoot It"

If you take a room-temperature shot of pastel de nata liqueur, you are going to get a sugar rush and a slightly syrupy coating on your tongue that lingers for an hour. It’s too much. Instead, the Portuguese (and the few bartenders globally who have started playing with this stuff) treat it like a component rather than a solo act.

Think about it this way: you wouldn't drink a cup of straight maple syrup. You put it on things.

The Coffee Connection

The best way to use this stuff, hands down, is in coffee. In Portugal, there’s a long tradition of the mazagran or the café com cheirinho (coffee with a "little scent" of alcohol, usually aguardente). Swapping the harsh aguardente for a splash of pastel de nata liqueur transforms a standard espresso into something that feels like a dessert.

- The "Nata Macchiato": Pull a double shot of espresso and stir in 20ml of the liqueur. No sugar needed.

- The Iced Version: Shake it with cold brew and plenty of ice. The dilution from the melting ice actually helps open up the cinnamon notes.

Using Pastel de Nata Liqueur in Cocktails (That Aren't Gross)

Bartenders are usually skeptical of "gimmick" liqueurs. They’re hard to balance because they bring so much sugar to the party. However, if you treat this liqueur as a replacement for simple syrup and cream in a recipe, it starts to make sense.

Consider the Espresso Martini. Usually, it’s vodka, espresso, and Kahlúa. If you swap the Kahlúa for pastel de nata liqueur, you get a "Pastel Martini" that has a much creamier mouthfeel and a distinct cinnamon finish that Kahlúa lacks.

The Portuguese Flip

A traditional Flip cocktail uses a whole egg, sugar, and a spirit. It’s frothy and rich. You can bypass the mess of the egg by using the liqueur.

- Mix 40ml of aged rum (the funkier, the better—think something from Madeira or a Jamaican pot still).

- Add 30ml of pastel de nata liqueur.

- Shake violently with ice.

- Strain into a chilled glass and grate fresh cinnamon on top.

The freshness of the cinnamon is vital. The stuff already in the bottle is "cooked" tasting; the fresh dust on top gives you that olfactory hit you get when walking past a bakery in Santa Maria Maior.

Myths vs. Reality: Does it actually expire?

People ask this all the time because of the cream content. Unlike a bottle of Gin or Vodka that will survive a nuclear winter, pastel de nata liqueur has a shelf life. Most manufacturers recommend finishing the bottle within six months to a year after opening.

And for the love of everything holy, keep it in the fridge once it’s open.

If you see it starting to separate or if the color shifts from a vibrant "egg-yolk yellow" to a duller beige, it’s time to toss it. The fats in the dairy can go rancid. It’s not going to kill you, but it’ll taste like a bad memory.

Beyond the Glass: Baking with the Stuff

If you bought a bottle and realized you hate drinking it, don't pour it down the sink. It’s a secret weapon for bakers. Because it’s essentially stable, alcoholic custard, you can use it to soak sponge cakes or spike a frosting.

Try replacing the milk in a French Toast recipe with a 50/50 mix of milk and liqueur. The alcohol burns off, leaving behind a caramelized crust that tastes more like a real pastel de nata than the liqueur does on its own. It’s a weirdly meta way to eat breakfast.

Finding the Good Stuff

Not all pastel de nata liqueurs are created equal. You’ll find "tourist traps" in plastic bottles at the airport that taste like chemicals. If you want the real deal, look for these names:

Licor 35: The gold standard. It’s the one that popularised the category. It’s balanced and has a very distinct "crust" flavor that others miss. It was created by Paulo Ferreira, who spent over a year trying to get the recipe right so it wouldn't taste like "just another cream liqueur."

Liqueur of Portugal (various artisanal brands): Sometimes you’ll find smaller batches in local garrafeiras (wine shops). These often have a higher alcohol burn but use better quality cinnamon.

Casal dos Jordões: They are known for their organic Port wines, but their foray into liqueurs is surprisingly high-quality, focusing more on the natural sweetness of the grapes as a base.

Is it a "Real" Portuguese Tradition?

Purists will tell you no. If you ask a 90-year-old grandmother in Alfama if she drinks pastel de nata liqueur, she’ll probably laugh and offer you a Ginjinha (cherry liqueur) instead. Ginjinha is the actual historical liqueur of Lisbon.

Pastel de nata liqueur is a child of the 21st century. It’s a response to the global obsession with the pastry itself. But just because it’s new doesn't mean it’s bad. It’s a fun, kitschy evolution of Portuguese food culture. It represents the country's ability to take its most iconic symbol and turn it into something portable.

A Quick Word on Temperature

If you insist on drinking it neat, it must be ice cold. Not "cool." Ice cold. Keep the bottle in the back of the fridge. Use a small glass. Don't add ice cubes to the glass—they melt and make the liqueur look watery and unappealing. Use whiskey stones or just chill the glassware beforehand.

How to Spot a "Fake" Experience

In Lisbon, you might see places offering "Pastel de Nata shots" in chocolate cups. This is peak tourism. While it’s tasty, the chocolate completely masks the nuances of the liqueur. If you want to actually taste the cinnamon and the citrus notes of the pastel de nata liqueur, skip the chocolate cup.

Drink it from a glass.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Bottle

If you’ve got a bottle sitting on your bar cart, or you're planning to buy one, here is how to actually enjoy it without getting a sugar headache.

First, check the production date. If it’s been on a dusty shelf for three years, leave it there. Freshness matters for cream liqueurs.

👉 See also: Why 2 Home Farm Alkrington is More Than Just a Postcode

Second, do a side-by-side. Buy a real pastel de nata from a bakery. Take a bite. Then take a tiny sip of the liqueur. You’ll notice the liqueur is much heavier on the lemon. Use this knowledge to your advantage—add a twist of lemon peel to any drink you make with it to bridge that gap.

Third, stop thinking of it as a shot. Start thinking of it as a "syrup plus." Use it over vanilla bean ice cream. Use it in your Sunday morning latte. Use it to deglaze a pan when making caramelized apples.

The complexity of pastel de nata liqueur is often buried under its own sweetness. By diluting it, chilling it, or mixing it with bitter elements like coffee or dark spirits, you actually get to taste the craftsmanship that went into the bottle. It’s a tribute to a pastry that took centuries to perfect, so it deserves a bit more respect than a quick gulp at the airport gate.

Go find a bottle of Licor 35, grab some high-quality espresso, and skip the sugar. That’s the closest you’ll get to a Lisbon morning without buying a plane ticket. Just remember to put the cork back in tight and shove it in the fridge, or you’ll be greeted by a very funky surprise in a few months.