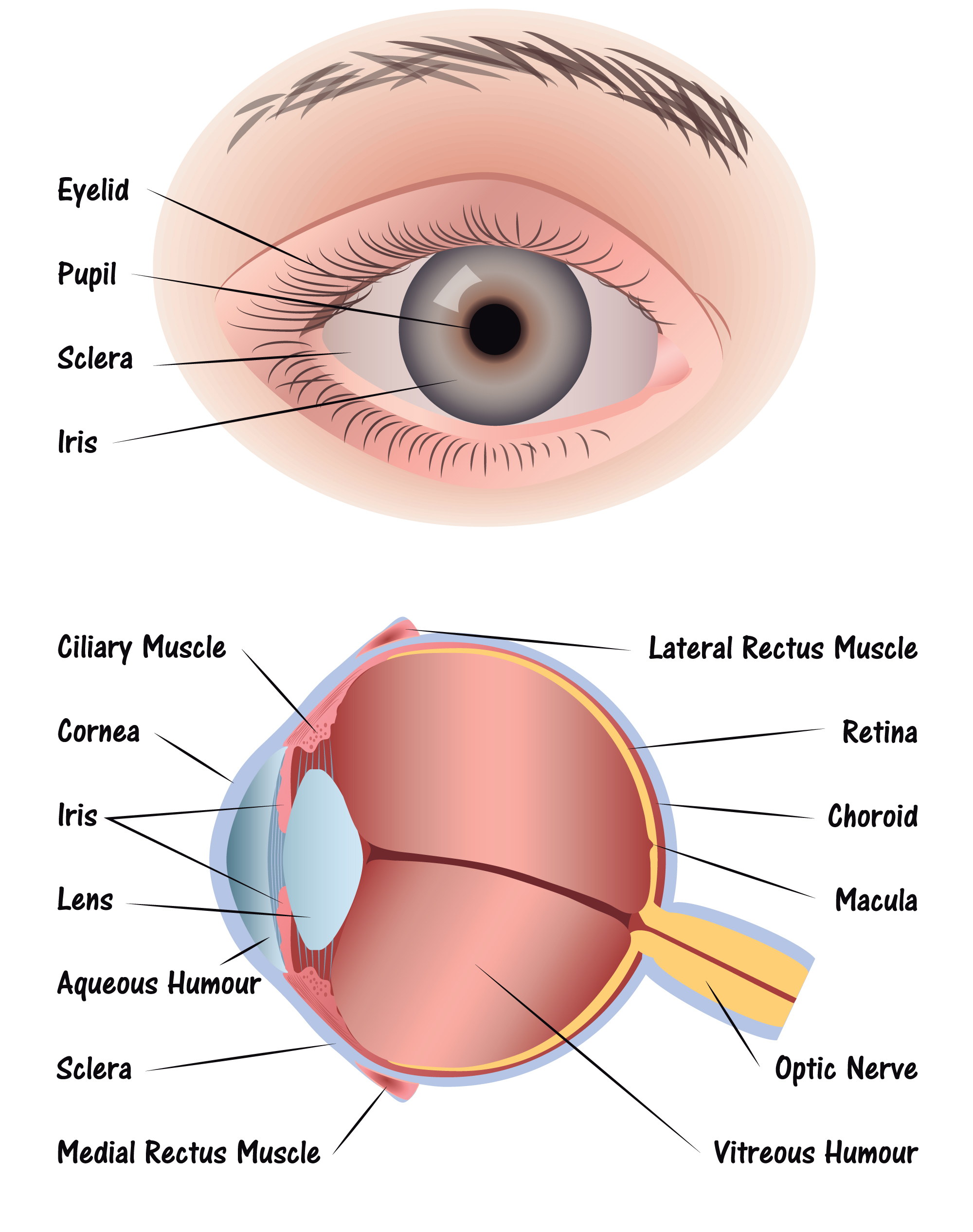

You’ve probably seen the diagram. It’s that cross-section of a giant, floating orb that looks more like a weirdly layered onion than something that helps you see the world. In high school biology, it was just another thing to memorize for the midterm. But honestly, if you’re dealing with blurry vision, weird floaters, or just wondering why your eyes get so dry after staring at a screen for eight hours, the parts of the eye diagram actually start to matter quite a bit. It isn't just a map. It’s a complex mechanical system where if one tiny piece gets slightly out of alignment, everything goes sideways.

Eyes are weird. They’re basically liquid-filled cameras made of protein and water.

Most people think vision happens in the eye. That’s not really true. The eye is just the data collector. It grabs light, bends it, and turns it into electrical zaps that your brain has to figure out later. If you look at a standard anatomical chart, you’ll see about a dozen main labels, but the interaction between those parts is where the real magic—and the real problems—happen.

The Front Line: Cornea and Iris

The cornea is the clear window at the front. It’s the only living tissue in the human body that doesn't contain blood vessels. Think about that for a second. If it had blood vessels, you’d be looking through a red haze all day. Instead, it gets oxygen directly from the air and nutrients from the "aqueous humor," which is the watery fluid sitting right behind it. When you get a "scratched eye," you're usually talking about a corneal abrasion. Because the cornea is packed with nerve endings, it hurts like absolute hell. It’s actually one of the most sensitive parts of your entire body.

Then you have the iris. This is the part everyone cares about because it determines if you have "dreamy" blue eyes or "soulful" brown ones. But the iris is just a muscle. It’s a circular sphincter that controls the size of your pupil.

When you walk into a dark room, your iris relaxes, making the pupil larger to let in more light. Move into bright sunlight, and it cinches shut. This is why "dilation" at the eye doctor is so annoying. They use drops to paralyze that iris muscle so it stays wide open, allowing the doctor to see into the back of the eye without the "window" constantly trying to close on them.

The Lens and the Focusing Struggle

Right behind the iris sits the lens. In a parts of the eye diagram, it looks like a little transparent M&M. Unlike the lens in a Nikon camera, which is made of glass or plastic, your biological lens is flexible. It changes shape.

When you look at something close up, like your phone, tiny muscles called ciliary muscles squeeze the lens, making it fatter. This increases its refractive power. This process is called accommodation.

📖 Related: Products With Red 40: What Most People Get Wrong

Here’s the catch: as we get older, that lens starts to lose its flexibility. It becomes more like a piece of stiff plastic than a soft gel. This is why almost everyone over the age of 45 eventually needs reading glasses. It's not that your eyes are "broken," it's just that the lens has physically hardened and can no longer "fatten up" to focus on close objects. This is also where cataracts happen. Over time, the proteins in the lens start to clump together. It’s a lot like an egg white turning opaque when you cook it. Eventually, that clear window becomes a foggy mess.

The Vitreous Humor: The Jelly Center

The vast majority of the eye’s volume isn't actually "hardware." It’s a space filled with a clear, jelly-like substance called the vitreous humor. It’s mostly water and collagen. Its main job? Keeping the eye round. Without that internal pressure, the eyeball would collapse like a deflated soccer ball.

If you’ve ever seen "floaters"—those little wiggly lines or dots that drift across your vision—you’re actually seeing shadows. As we age, the vitreous jelly starts to liquefy and shrink. Sometimes, tiny clumps of collagen fibers cast shadows on the retina. You aren't seeing bugs; you're seeing the debris inside your own eye's internal fluid.

Most floaters are harmless. However, if you suddenly see a massive "curtain" falling over your vision or a sudden explosion of new floaters, that’s a medical emergency. It usually means the vitreous is pulling away from the back of the eye so hard that it’s tearing the retina.

The Retina: The High-Tech Sensor

If the eye is a camera, the retina is the digital sensor. It’s a thin layer of tissue that lines the back of the eye. It’s incredibly delicate—sorta like wet tissue paper.

The retina is packed with photoreceptors: rods and cones.

- Rods handle low light and peripheral vision.

- Cones handle color and fine detail.

In the very center of the retina is a tiny spot called the macula. This is the "high-definition" zone of your vision. When you read a book or look at a face, you are using your macula. This is why Macular Degeneration is so devastating. The person might still have their peripheral vision (thanks to the rest of the retina), but the center of their world becomes a dark, blurry hole.

👉 See also: Why Sometimes You Just Need a Hug: The Real Science of Physical Touch

The retina takes the light it receives and converts it into electrical signals. These signals travel through the optic nerve. Interestingly, the spot where the optic nerve connects to the retina has no photoreceptors. This is your "blind spot." Your brain is just really good at "Photoshopping" that hole out of your daily life so you don't notice it.

The Sclera and the Choroid: The Support System

The white of your eye is the sclera. It’s tough, fibrous, and meant for protection. It’s the "shell" of the orb. Underneath the sclera sits the choroid.

The choroid is basically a massive plumbing system of blood vessels. It provides oxygen and nourishment to the outer layers of the retina. Without the choroid, the retina would starve and die within minutes. In many animals, the choroid has a reflective layer called the tapetum lucidum, which is why a cat's eyes glow in the dark. Humans don't have that, which is why we’re pretty terrible at seeing in total darkness compared to our feline friends.

Why the Diagram Often Misleads Us

Most parts of the eye diagram you find online or in textbooks are 2D and static. They make the eye look like a series of separate parts glued together. In reality, it’s a pressurized system.

Glaucoma is a perfect example of why the "system" view matters. Your eye is constantly producing fluid (aqueous humor) in the front chamber and draining it out through a tiny meshwork. If that drain gets clogged, the pressure inside the entire eye rises. Because the sclera is so tough, the pressure can't go "out." It goes "back." It ends up crushing the delicate fibers of the optic nerve.

By the time someone notices they're losing vision from glaucoma, the damage is usually permanent. This is why eye exams involve that annoying "puff of air" or a little blue light touching your eye—they’re measuring the internal pressure to make sure the "plumbing" is working right.

Real-World Protection for Your Anatomy

Understanding the anatomy is cool, but how do you actually keep these parts from breaking down?

✨ Don't miss: Can I overdose on vitamin d? The reality of supplement toxicity

UV Protection isn't just for fashion. The lens and the retina are particularly sensitive to ultraviolet light. Cumulative UV exposure is a major risk factor for both cataracts and macular degeneration. If your sunglasses don't say "100% UV Protection" or "UV400," they’re basically just tinted plastic that's doing nothing for your eye health.

The 20-20-20 Rule. Your ciliary muscles (the ones that squeeze the lens) get "cramps" just like any other muscle. If you stare at a screen for four hours, those muscles are locked in a state of contraction. Every 20 minutes, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds. This allows the muscles to relax and the lens to flatten out.

Omega-3s and the Tear Film. The very outermost part of the eye isn't even a tissue—it’s the tear film. It has three layers: oil, water, and mucus. If the oil layer (produced by the Meibomian glands in your eyelids) is weak, your tears evaporate too fast. This leads to chronic dry eye. Eating healthy fats and staying hydrated helps maintain that "oil slick" that keeps your eyes lubricated.

Stop rubbing your eyes. Seriously. Rubbing your eyes aggressively can actually thin the cornea over time, leading to a condition called keratoconus where the cornea bulges out into a cone shape. It can also rupture tiny blood vessels in the conjunctiva (the clear membrane over the white part), giving you that "bloody eye" look.

Moving Beyond the Chart

The human eye is an engineering marvel that manages to be both incredibly resilient and frustratingly fragile. While a parts of the eye diagram gives you the names of the "players," it's the chemistry and physics between them that allow you to read these words right now.

If you're noticing changes—even small ones—don't ignore them. Most eye conditions are significantly easier to treat when they’re caught before the anatomy itself is permanently altered.

Next Steps for Your Eye Health:

- Check your sunglasses: Verify they have a UV400 rating; if not, replace them before the next sunny season.

- Audit your screen setup: Ensure your monitor is at least an arm's length away to reduce the constant strain on your ciliary muscles.

- Schedule a dilated exam: If it's been more than two years, get an exam where they actually look at the retina and optic nerve, not just a "which is better, one or two" vision test.

- Monitor "Floaters": If you see a sudden "shower" of sparks or black dots, go to an emergency eye clinic immediately to rule out a retinal tear.