Your knee is basically a mechanical masterpiece that’s somehow expected to hold up your entire body weight while you sprint, pivot, or just haul groceries up the stairs. It’s the largest joint you own. Honestly, it’s a bit of a design miracle, but it’s also remarkably fragile if you don't understand how the different parts of human knee actually interact. Think of it like a high-end suspension system on an off-road vehicle—if one bolt shears or a single spring loses its tension, the whole ride turns into a noisy, painful mess.

Most people think of the knee as a simple hinge. It’s not. It’s a "modified hinge," which means it doesn't just swing back and forth; it also rotates and slides. This complexity is why the parts of human knee are so prone to injury. When you look at the anatomy, you're seeing a violent collision of bone, cartilage, and cables that have to work in perfect sync or you’re headed for an MRI.

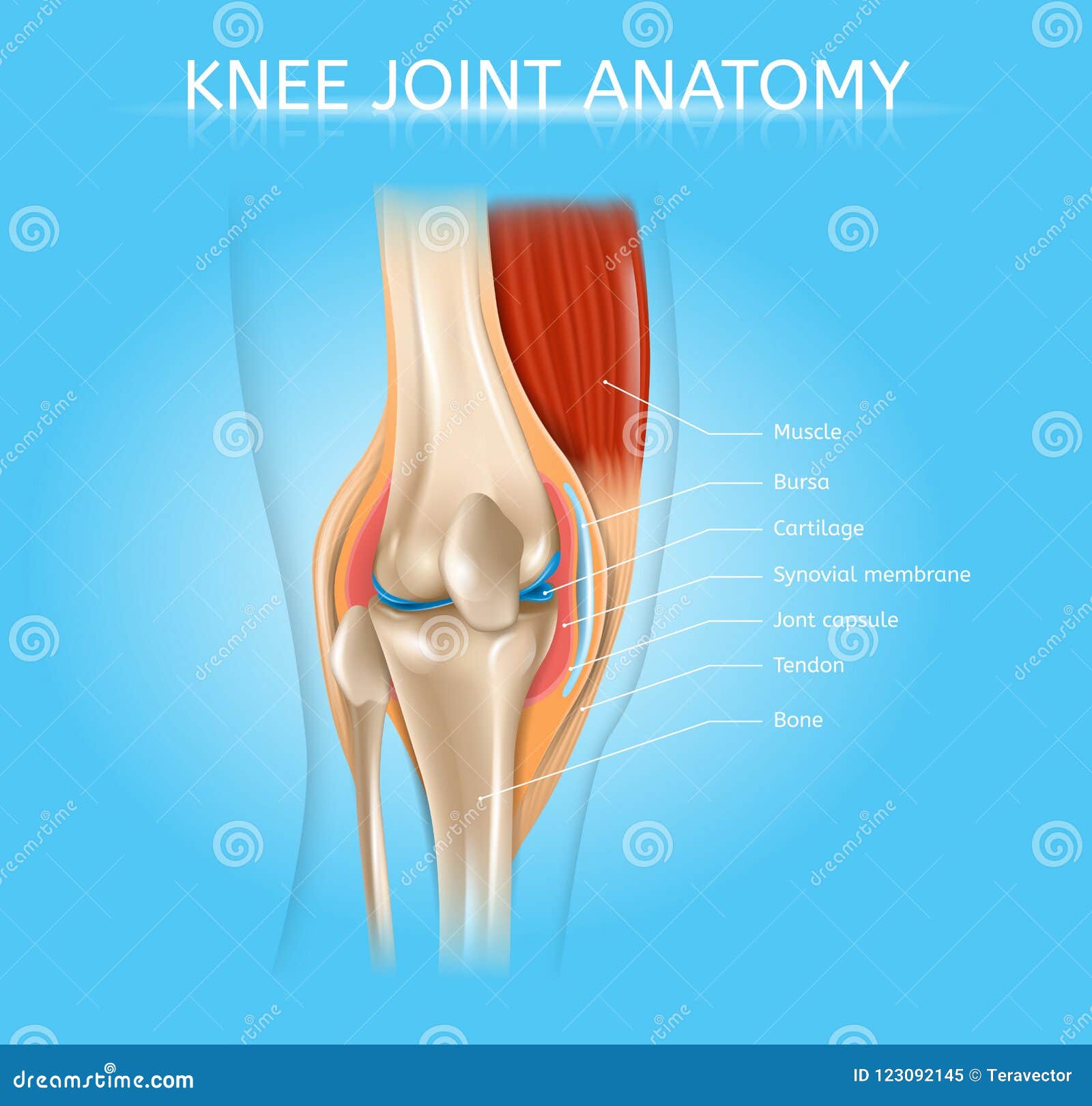

The Bones: The Foundation of the Knee

At the core, you’ve got three main players. There's the femur (your thigh bone), the tibia (the shin bone), and the patella, which most of us just call the kneecap. The fibula is there too, that thin bone on the outside of your lower leg, but it doesn't actually sit inside the joint. It mostly acts as an anchor for ligaments.

The femur is a beast. It’s the longest and strongest bone in your body, ending in two rounded knobs called condyles. These condyles sit on top of the tibia’s flat surface, known as the tibial plateau. If you’ve ever seen a knee replacement surgery—or even just a model—you’ll notice how precarious this looks. It’s basically a round ball sitting on a flat shelf. Without the other parts of human knee holding it together, your leg would just slide right off itself.

Then there's the patella. This little sesamoid bone lives inside a tendon. It’s not just there for protection; it acts as a lever. By sitting in front of the joint, it increases the mechanical advantage of your quadriceps muscle, making it easier for you to kick or stand up from a chair. Without a kneecap, you'd need about 30% more muscle power just to straighten your leg.

Ligaments: The Cables Holding the Chaos Together

If the bones are the frame, the ligaments are the heavy-duty steel cables. You probably know the ACL. It’s the one athletes are terrified of tearing. The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) sits right in the middle of the joint, preventing the tibia from sliding too far forward. It’s tiny—about the size of a Pink Pearl eraser—but it handles immense torque.

Then you have its partner, the PCL (Posterior Cruciate Ligament), which stops the tibia from sliding backward. These two cross each other like an "X," which is why they’re called "cruciate" (Latin for cross). They provide the internal stability that keeps your femur from drifting.

On the sides, you have the collateral ligaments. The MCL (Medial Collateral) is on the inside of your knee, and the LCL (Lateral Collateral) is on the outside. These are your side-to-side stabilizers. If you get hit from the side during a football game, the MCL is usually what takes the hit. It's surprisingly good at healing itself compared to the ACL because it has a better blood supply.

Biology is weird like that. Some parts of human knee are built to bounce back, while others are "one and done" without a surgeon’s help.

Cartilage and the Meniscus: The Shock Absorbers

You can’t have bone rubbing on bone. That’s a recipe for a nightmare called osteoarthritis. To prevent this, the ends of your bones are coated in articular cartilage. This stuff is slicker than ice on ice. It’s a white, glossy tissue that allows the bones to glide over each other with almost zero friction.

✨ Don't miss: Night guard for jaw clenching: What you're probably getting wrong about your teeth

But the real stars of the show are the menisci.

You have two of them: the medial and lateral meniscus. They are C-shaped pads of fibrocartilage that act like wedges. Because the femur is round and the tibia is flat, the meniscus fills that gap, distributing your weight across a larger surface area. If you didn't have them, the pressure on your tibial plateau would be high enough to literally crush the bone over time.

Dr. Robert LaPrade, a world-renowned complex knee surgeon, often emphasizes that the meniscus is the "brain" of the knee. It’s sensitive, it provides feedback, and once it’s gone, you can’t really grow it back. Most "wear and tear" people feel in their 40s is just the meniscus slowly fraying like an old rug.

Why Your Knee Makes Those Weird Noises

Is it bad if your knee pops? Not necessarily. That sound—crepitus—is often just gas bubbles popping in the synovial fluid or a tendon snapping over a bony prominence. However, if the popping comes with pain or swelling, one of the parts of human knee is likely snagged.

Synovial fluid is the "oil" in the machine. It’s a thick, viscous liquid that lubricates the joint and nourishes the cartilage. Cartilage doesn't have its own blood supply, so it relies on this fluid to bring in nutrients. This is why movement is medicine. When you move, you're basically "pumping" the fluid into the cartilage.

- Fact Check: Sitting all day actually starves your knee cartilage of nutrients.

- Pro Tip: If your knee locks up and won't move, that’s usually a "bucket handle tear" of the meniscus getting caught in the hinge. See a doctor. Fast.

Muscles: The Power Plants

You can have the strongest ligaments in the world, but if your muscles are weak, your knee is a ticking time bomb. The quadriceps on the front and the hamstrings on the back are the primary movers.

The "quads" are responsible for straightening the leg. They pull on the patella, which pulls on the tibia. If your quads are weak, the patella doesn't track correctly in its groove, leading to "runner's knee."

The hamstrings are the brakes. They help the ACL prevent the shin bone from sliding forward. This is why many physical therapists, like those following the "Prehab" protocols, focus heavily on hamstring and glute strength for ACL injury prevention. If your butt and hams are strong, they take the load off the ligaments.

Don't forget the calves (gastrocnemius). They actually cross the back of the knee joint and contribute to its stability. It’s all connected. You can’t fix a knee problem by only looking at the knee. You have to look at the hip and the ankle too.

Common Misconceptions About Knee Health

People love to say that running ruins your knees. Science actually says the opposite.

A study published in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy found that recreational runners actually had lower rates of hip and knee osteoarthritis compared to sedentary individuals. Running, when done with proper progression, actually strengthens the parts of human knee by thickening the cartilage and strengthening the surrounding bone.

✨ Don't miss: Red 40 Revealed: Why It’s in Everything and How to Spot It

The danger isn't the running; it’s the "too much, too soon" approach.

Another myth: "I have bone-on-bone, so I shouldn't exercise."

While it sounds scary, movement often reduces pain by increasing blood flow and strengthening the muscles that act as secondary stabilizers. You’re not "wearing it out" like a brake pad; you’re a biological organism that adapts to stress.

How to Protect Your Knee Parts Long-Term

If you want to keep your original parts well into your 80s, you need a strategy. You can't just hope for the best.

First, manage your weight. This isn't a lecture; it's physics. For every pound you lose, you take about four pounds of pressure off your knee joint during every step. If you’re running or jumping, that pressure is multiplied by seven or eight.

Second, work on your "terminal knee extension." This is the ability to fully straighten your leg. If you lose those last few degrees of extension due to swelling or tightness, your quad can't fire properly, and the whole mechanics of the parts of human knee go out the window.

Third, balance training. Stand on one leg while you brush your teeth. This forces the tiny "proprioceptive" nerves in your ligaments to fire, teaching your brain how to stabilize the joint instantly if you trip on a curb.

Actionable Steps for Knee Longevity

- Assess your mobility: Sit on the floor with your legs straight. Can you push the back of your knee all the way into the floor? If not, work on your calf and hamstring flexibility.

- Strengthen the VMO: The Vastus Medialis Obliquus is the teardrop-shaped muscle on the inside of your thigh. It’s the primary stabilizer for the kneecap. Split squats and "Poliquin step-ups" are gold for this.

- Update your footwear: If your shoes are worn out on one side, they’re forcing your knee into a permanent tilt. Change them every 300-500 miles if you're active.

- Cross-train: If you only run, your joints only experience one type of stress. Throw in some swimming or cycling to lubricate the joint without the impact.

- Listen to the "Heat": A warm knee is an inflamed knee. If one knee feels noticeably warmer than the other after a workout, you’ve overstressed the internal tissues. Back off and use ice or compression.

Taking care of the parts of human knee isn't just about avoiding surgery; it's about maintaining your freedom. When your knees go, your world gets very small. Keep the hinges oiled, the cables tight, and the motor strong.