You’re standing at the meat counter, or maybe you’re looking at a whole hog carcass hanging in a cold room, and it hits you. Most of us have no idea what we’re actually looking at. We know "bacon" and we know "pork chops," but the actual breakdown of parts of a hog is a masterpiece of biological efficiency that most modern grocery shoppers have completely lost touch with. It’s kinda wild when you think about it. We’ve been domesticated alongside these animals for roughly 9,000 years, yet if I asked the average person where a St. Louis-style rib comes from versus a baby back, they’d probably just point vaguely at the middle of the animal and hope for the best.

Understanding the hog isn't just for farmers or industrial processors. If you want to save money—and honestly, who doesn't right now?—knowing these cuts is your secret weapon. You can buy a whole pork loin for a fraction of the price of pre-cut chops. But you have to know what you’re doing with the knife.

The Primal Cuts: It All Starts Here

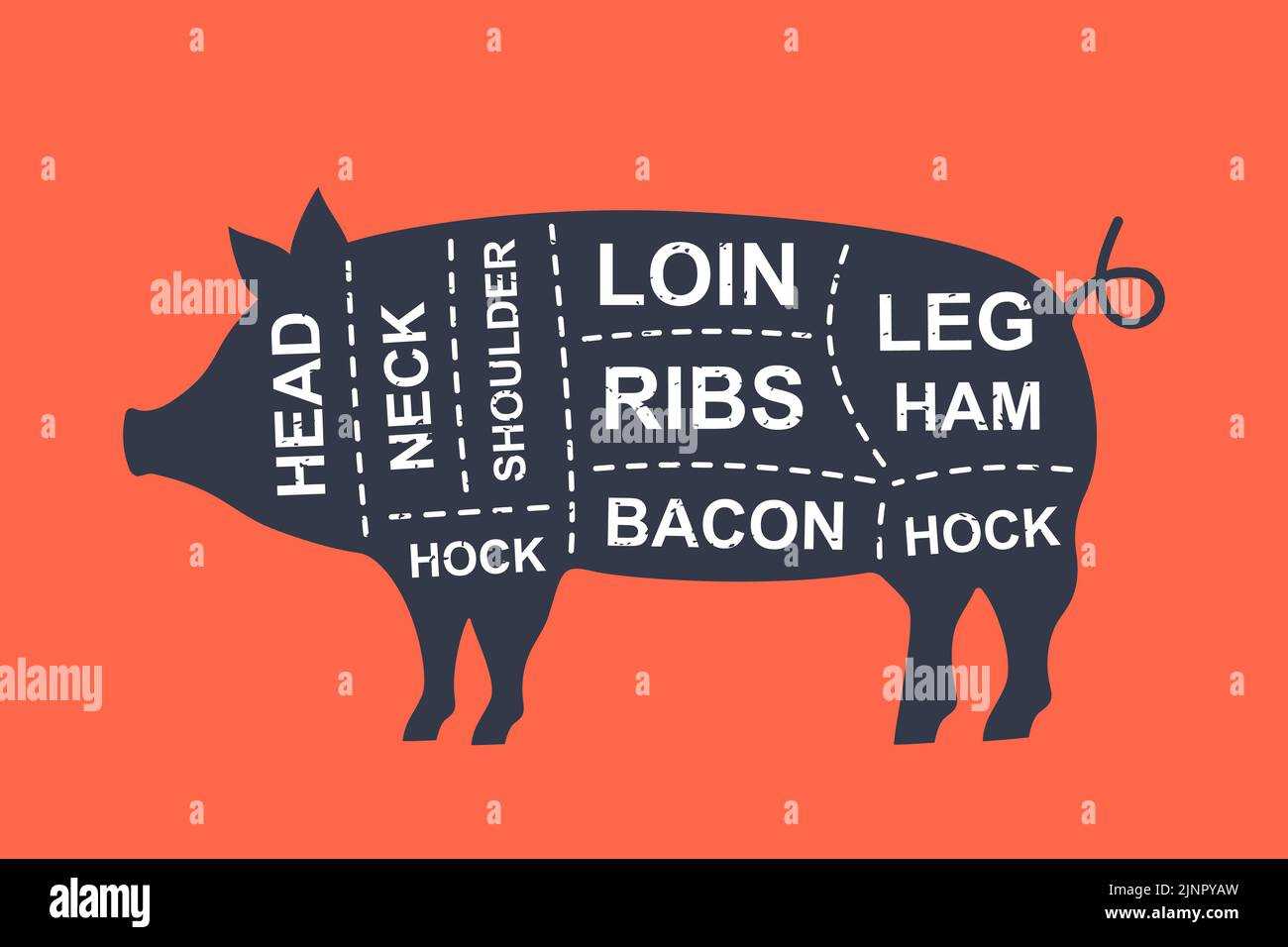

Before we get into the weird stuff like the "secret" butcher's cuts, you have to understand the four main pillars. In the industry, we call these the primals. Basically, they are the four big sections the carcass is split into before it becomes the recognizable packages you see under plastic wrap.

First, you've got the Shoulder. This is the workhorse. It’s further divided into the Picnic Shoulder (the lower part) and the Boston Butt (the upper part). Wait, why is it called a "butt" if it's on the front of the pig? History is weird. Back in the day, these cheaper cuts were packed into barrels called "butts" for shipping. The name stuck. The Boston Butt is arguably the most forgiving piece of meat on the planet. Because it's packed with intramuscular fat and connective tissue—specifically collagen—you can basically ignore it in a smoker for ten hours and it’ll still taste incredible. If you try that with a loin, you’re eating shoe leather.

Then there’s the Loin. This is the long stretch of muscle along the back. It’s where the high-dollar stuff lives. Think tenderloin, loin roasts, and those iconic bone-in chops. It’s lean. It’s delicate. It’s also the most commonly overcooked part of the hog.

Moving Down the Line

The Belly is exactly what it sounds like. It’s the underside. This is where bacon comes from, obviously, but it’s also the source of spare ribs. The fat-to-meat ratio here is through the roof. Finally, you have the Leg, which most people just call the Ham. Most hams you buy are cured or smoked, but a fresh "green" ham is a massive, lean roast that is criminally underrated in American kitchens.

Why the Shoulder is Actually the Best Part

If you ask a competitive BBQ circuit pro like Myron Mixon or Aaron Franklin about their favorite parts of a hog, they aren’t going to point at the tenderloin. They’re going for the shoulder. Specifically the Boston Butt.

Here’s the thing about pork fat: it has a lower melting point than beef fat. When you slow-cook a shoulder, that fat renders out and bastes the meat from the inside. But the real magic is the connective tissue. Through a process called hydrolysis, collagen turns into gelatin at around $160°F$ to $180°F$. This gives the meat that "silky" mouthfeel that makes pulled pork so addictive.

👉 See also: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

- The Picnic: Often overlooked. It’s tougher than the butt and usually comes with the skin on. Great for crackling.

- The Hock: This is the joint where the foot attaches. It’s all bone, skin, and tendons. You don’t eat it as a main; you throw it in a pot of collard greens or beans and let it give up its soul to the broth.

The Loin and the Rib Confusion

Let's clear this up once and for all because the "rib" terminology is a mess.

Baby back ribs are not from baby pigs. They’re called "back" ribs because they are attached to the loin—high up on the hog’s back. They are shorter, curved, and leaner. Spare ribs, on the other hand, come from the belly. They are flatter, meatier, and have a lot more gristle. If you trim the sternum and cartilage off a spare rib, you get a "St. Louis Cut."

The loin itself is the source of the Pork Tenderloin. This is the psoas major muscle. It does almost no work, which is why it’s so soft. But because it has almost zero fat, it’s remarkably easy to ruin. If you hit $150°F$ internal temperature, you’ve gone too far. Aim for $145°F$ with a good rest.

The "Fifth Primal": The Head and the Odd Bits

We live in a culture that’s a bit squeamish about the head, but honestly, you’re missing out on some of the most flavorful parts of a hog.

The Jowl is basically bacon but better. It’s the cheek. In Italy, they cure it to make Guanciale. If you’ve ever had a truly authentic Pasta alla Carbonara, that funky, silky fat came from the hog’s jowl. It’s richer than belly bacon and holds its structure better when rendered.

Then there’s the Ears and Snout. These are high-cartilage areas. In many Asian cuisines, particularly Filipino (think Sisig), these are chopped and fried until crispy. The texture is the selling point here—crunchy, chewy, and intensely savory.

And we can’t talk about the head without mentioning Head Cheese. It’s not cheese. It’s a terrine made from the meat of the head, set in its own natural gelatin. It’s a bit "old world," but for a charcuterie fan, it’s the gold standard of nose-to-tail eating.

✨ Don't miss: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

Comparing the Cuts: A Quick Reality Check

If you’re looking for a specific result, you need the right part. You can't just swap them out and expect the same dinner.

For Grilling (Fast and Hot):

You want the Loin or the Tenderloin. These cuts don't have the connective tissue that needs time to break down. If you put a piece of belly on a high-heat grill without a plan, you’re going to start a grease fire.

For Smoking (Low and Slow):

Shoulder (Butt or Picnic) or the Belly. These need the "stall"—that period where moisture evaporates and temperatures plateau—to properly tenderize.

For Braising (Wet Heat):

Shanks or Hocks. These are the "legs" basically. They are tough as nails until they sit in a liquid for three hours. Then the meat just falls off the bone in these beautiful, long strands.

The Secret "Butcher's Cuts" You Need to Ask For

Most people walk into a grocery store and see the same five things. But if you go to a real butcher—someone who actually breaks down whole animals—you can find the "secret" parts of a hog.

One of these is the Secreto. It’s a thin, fan-shaped muscle hidden near the shoulder. It’s heavily marbled and often called the "wagyu of pork." In Spain, it’s a delicacy. In America, it often gets ground into sausage because people don't know what it is. If you see it, buy it. Sear it fast, slice it thin across the grain.

Another is the Iberico Pluma. This is the "end" of the loin near the shoulder. It’s got more fat than the rest of the loin and a much deeper flavor.

🔗 Read more: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

Nutritional Nuance and the "Other White Meat" Myth

Remember those commercials from the 90s? They tried to brand pork as "The Other White Meat" to compete with chicken. It was a marketing genius move but a culinary disaster. It encouraged farmers to breed hogs that were leaner and leaner, which eventually led to pork that tasted like... well, nothing.

The truth is that pork is red meat. Myoglobin levels in the muscle determine this. While the loin is quite lean (comparable to a skinless chicken breast), other parts of the hog are nutrient-dense powerhouses. Pork is an incredible source of B-vitamins, especially Thiamin ($B_1$), which helps your body turn carbs into energy.

The fat isn't the enemy either. About $45%$ of the fat in a hog is monounsaturated (the same kind found in olive oil). When you eat a pastured hog—one that actually got to run around and eat acorns or grass—the nutritional profile changes even more, offering higher levels of Omega-3 fatty acids.

Why "Nose to Tail" Matters in 2026

We're seeing a massive shift back to whole-animal butchery. It’s better for the environment, it’s more ethical, and it’s frankly more interesting for your palate. When we only eat the loin, we waste the majority of the animal.

Using the parts of a hog like the skin (for chicharrones), the bones (for tonkotsu-style ramen broth), and the organs (like the liver for pâté) honors the animal. It also forces you to become a better cook. Anyone can grill a chop. It takes skill to turn a trotter into a delicacy.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Trip to the Butcher

Don't just walk in and ask for "pork." Be specific. Here is how you should handle your next purchase to get the most value:

- Buy the whole loin. If it's on sale, grab the $8-10$ pound vacuum-sealed bag. Take it home, cut the center into thick chops, and save the ends for a roast or for dicing into stir-fry meat. You'll save at least $30%$ over buying individual chops.

- Ask for "Skin-On" Shoulder. If you’re roasting, that skin protects the meat and becomes a salty, crunchy treat. Most supermarkets trim it off, but it’s the best part.

- Look for "Heritage Breeds." If you see Berkshire (Kurobuta) or Mangalitsa, try it. The fat distribution in these breeds is vastly different from the standard "industrial" hog. The meat is darker, redder, and actually tastes like something.

- Save the bones. If you buy bone-in cuts, never throw the bones away. Keep a bag in your freezer. When it’s full, simmer them with an onion and a carrot for six hours. The resulting stock will make any soup you make taste like it came from a Michelin-star kitchen.

- Experiment with Jowl. Next time you’re making breakfast, skip the standard belly bacon and look for smoked jowl. It’s cheaper and more flavorful.

The parts of a hog offer a world of variety that goes far beyond a ham sandwich. Whether you're chasing the perfect bark on a smoked butt or trying to master the delicate sear of a secreto, understanding the anatomy is the first step toward better eating. Stop buying the same three cuts. Talk to your butcher, try the "weird" bits, and stop overcooking your loin. Your dinner table will thank you.