It is a strange sight if you're driving west of Phoenix. Out in the middle of the scorching Sonoran Desert, miles from any significant body of water, sit three massive concrete domes. This is the Palo Verde AZ nuclear power plant, and honestly, it shouldn't exist where it does. Most nuclear plants are hugging a coastline or perched next to a massive river because reactors are thirsty. They need millions of gallons of water to stay cool. But here, in a landscape defined by cactus and heatwaves, we have the largest power producer in the United States.

How? It’s basically a feat of engineering stubbornness.

While other plants are shutting down or struggling with aging infrastructure, Palo Verde remains the backbone of the Western grid. It doesn't just power Arizona; it keeps the lights on in California, New Mexico, and parts of Texas. It’s a beast. Since it started humming back in the 80s, it has produced more carbon-free electricity than any other single site in the country. But with the Southwest facing a historic megadrought and the energy market shifting toward renewables, people are starting to ask if this desert giant can actually survive the next few decades.

The Water Secret Nobody Talks About

Most people assume a nuclear plant in the desert must be draining the groundwater or sucking the Salt River dry. It’s not. In fact, Palo Verde is the only nuclear plant in the world that doesn’t use "fresh" water for cooling.

They use poop.

Well, treated sewage to be more specific. The plant has a long-standing agreement with the city of Phoenix and several surrounding municipalities. They take the treated effluent—water that people have flushed down their toilets or sent down their drains—and pipe it 28 miles through a massive pipeline to the plant. This is the ultimate "reduce, reuse, recycle" flex. The plant treats that water again at an on-site facility before it ever touches the cooling towers.

Without this specific arrangement, the Palo Verde AZ nuclear power plant wouldn’t have been built. Period. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) wouldn't have allowed it, and the local optics would have been a nightmare. Even today, the plant consumes about 20 billion gallons of this reclaimed water every year. Think about that volume for a second. It's a staggering amount of liquid moving through the desert to keep those fuel rods from getting too hot.

Why Arizona's Heat is a Feature, Not a Bug

Operating a reactor in 115-degree weather sounds like a recipe for a meltdown, or at least a massive efficiency loss. But the engineers at Palo Verde have actually turned the desert environment into a laboratory for extreme performance. Because the ambient air is so dry, the cooling towers work incredibly well through evaporation.

🔗 Read more: Finding an OS X El Capitan Download DMG That Actually Works in 2026

It's actually more efficient than plants in humid places like Florida or South Carolina.

The Economic Engine of Maricopa County

Money talks. And Palo Verde shouts.

The plant is operated by Arizona Public Service (APS), but it’s actually owned by a consortium of utilities including Salt River Project (SRP), El Paso Electric, and Southern California Edison. This isn't just a local utility project; it’s a regional investment. Economically, the impact is massive. We are talking about nearly 2,500 full-time employees. These aren't just "jobs," they are high-paying, specialized roles for nuclear engineers, security forces, and technicians.

The annual economic impact on Arizona is estimated at over $2 billion.

When the plant does its refueling outages—usually twice a year—the local economy gets a "refueling" of its own. Thousands of contractors descend on the Tonopah area. They fill up the hotels, they eat at the diners, and they buy gas. For a few weeks, this quiet patch of desert becomes a bustling industrial city. It's easy to forget that while we debate the pros and cons of nuclear energy, there are thousands of families whose entire livelihood depends on those three units staying online.

Safety Concerns and the "What If" Factor

Nuclear power always carries a weight of anxiety. It’s the nature of the beast. Mention the Palo Verde AZ nuclear power plant in a crowded room in Phoenix, and someone will eventually bring up Chernobyl or Fukushima. It’s unavoidable.

But here is the reality of the safety culture at the site.

💡 You might also like: Is Social Media Dying? What Everyone Gets Wrong About the Post-Feed Era

The plant is built to withstand things that simply don't happen in Arizona. We don't get tsunamis. We don't have major tectonic fault lines running directly under the reactors like they do at Diablo Canyon in California. The primary "threat" is the heat and the potential for long-term water shortages.

- Redundancy: Every system has a backup, and those backups have backups.

- Security: If you’ve ever tried to drive near the perimeter, you know the security is intense. It's basically a fortress.

- Waste Storage: This is the big sticking point. Since the U.S. still hasn't figured out a permanent national repository (looking at you, Yucca Mountain), the spent fuel stays on-site. It sits in "dry casks"—massive concrete and steel silos—out in the sun.

Is it ideal? No. Most experts agree that leaving radioactive waste scattered at plants across the country isn't the best long-term strategy. But for now, those casks are incredibly robust. They are designed to survive plane crashes, earthquakes, and extreme heat without leaking a drop of radiation.

Debunking the Radiation Myths

You aren't going to grow a third arm living in Buckeye.

Living near a nuclear plant actually exposes you to less radiation than you’d get from a couple of cross-country flights or even just the natural "background" radiation coming from the soil and the sun. The monitoring at Palo Verde is constant. There are sensors everywhere, and the results are public record. Honestly, the biggest risk to the surrounding community isn't a radiation leak; it’s the traffic on the I-10 during a shift change.

The Future: 2045 and Beyond

Palo Verde’s licenses were originally set to expire years ago, but the NRC granted 20-year extensions. This means the reactors are cleared to run until the mid-2040s.

But then what?

The energy landscape is messy right now. Arizona is a prime spot for solar, obviously. We have plenty of sun. But solar doesn't work at 2:00 AM when everyone's air conditioning is still blasting to combat the 95-degree nighttime lows. Battery storage is getting better, but it's not yet at the scale where it can replace the 3.9 gigawatts of steady, "baseload" power that Palo Verde spits out 24/7, regardless of whether the sun is shining or the wind is blowing.

📖 Related: Gmail Users Warned of Highly Sophisticated AI-Powered Phishing Attacks: What’s Actually Happening

Hydrogen: The Next Chapter?

There is some really cool stuff happening with hydrogen production at the site. The Department of Energy has been looking at the Palo Verde AZ nuclear power plant as a potential "hydrogen hub." Since the plant produces so much excess heat and electricity, they can use it to split water molecules and create clean hydrogen fuel.

This could be a game-changer.

Instead of just being a "power plant," Palo Verde could become a "fuel factory" for the trucking and shipping industries. It would give the site a purpose even as the grid becomes more saturated with solar and wind. It's a way to pivot from the 20th-century model of "big central power" to a 21st-century "energy platform."

Why This Matters to You Right Now

If you live in the Southwest, your electricity bill is directly tied to the health of this plant. When one of the units goes down for maintenance, the utilities have to buy power on the "spot market," which is almost always more expensive and usually involves burning natural gas.

Palo Verde keeps prices stable.

It also keeps the air cleaner. Arizona has some of the worst air quality in the country during the summer months due to ozone and dust. If we replaced Palo Verde with gas plants, the carbon footprint of the state would skyrocket overnight. We’re talking about preventing roughly 13 million metric tons of CO2 emissions every year. That’s the equivalent of taking nearly 3 million cars off the road.

Actionable Steps for the Energy-Conscious Arizonan

If you want to understand how your local energy ecosystem works, don't just take my word for it. You can actually get involved or learn more through a few direct channels.

- Check the NRC Reports: The Nuclear Regulatory Commission publishes "Daily Power Reactor Status Reports." You can see exactly what percentage of power each unit at Palo Verde is generating at any given moment. It’s a fascinating look at the "heartbeat" of the grid.

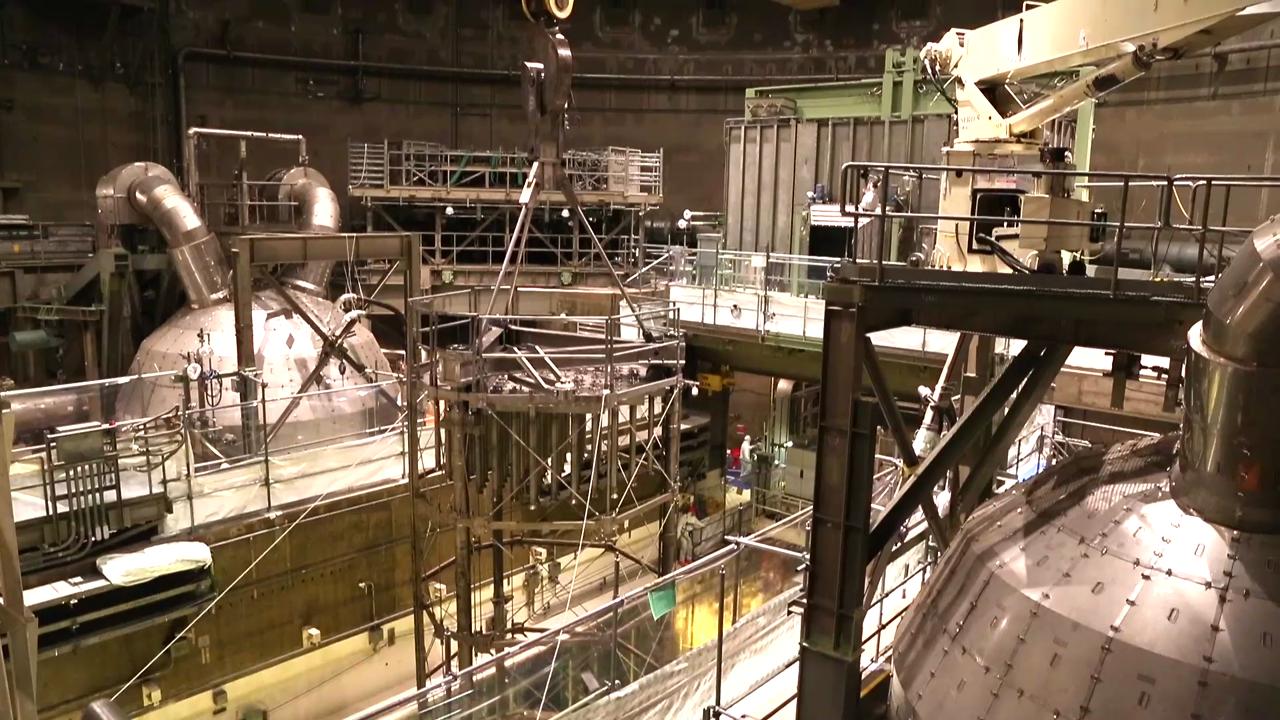

- Tour the Energy Education Center: While you can't just wander into the reactor core for obvious reasons, APS operates an Energy Education Center that offers programs for students and the public. It’s the best way to see the scale of the operation without being tackled by security.

- Monitor the ACC: The Arizona Corporation Commission (ACC) is where the real decisions happen. They decide how much you pay for power and what the "energy mix" should look like. If you care about the future of nuclear vs. solar, their public meetings are where your voice actually matters.

- Analyze Your Bill: Look at your "Fuel Mix" disclosure on your utility statement. Most Arizona residents will see that a massive chunk—often 20% to 30%—of their "clean" energy is actually coming from Palo Verde.

The Palo Verde AZ nuclear power plant is a paradox. It’s a high-tech marvel in a primitive landscape. It’s a water-hungry beast that thrives on waste. And it’s a 40-year-old facility that might just be the key to our future energy transition. Whether you love nuclear or hate it, you have to respect the sheer audacity of building a power plant that uses the city's leftovers to keep the desert cool.

As we move toward 2050, the conversation around Palo Verde will only get louder. The licenses will eventually come up for renewal again, or the talk of decommissioning will start for real. Until then, the domes will keep sitting out there in Tonopah, quietly churning out the electrons that make modern life in the desert possible.