Blaze Foley was a ghost before he even died. Most folks know him as the guy who lived in a treehouse, the duct-tape messiah who inspired Townes Van Zandt’s "Blaze’s Blues" and Lucinda Williams’ "Drunken Angel." But if you really want to understand the man, you have to look at the Oval Room Blaze Foley connection. It’s more than just a song title. It’s a snapshot of a guy who couldn't help but sabotage his own luck, even when the lights were brightest.

He was a big man. Loud. Smelled like cigarettes and cheap wine.

The "Oval Room" refers to a specific period and a specific place—the Oval Room at the Austin City Council, or more broadly, the political and social atmosphere of Austin in the late 1980s that Blaze found so utterly repulsive. He wasn't exactly a political analyst. He was a provocateur. When Blaze sang about the Oval Room, he wasn't just talking about architecture; he was taking aim at the "big shots" and the phonies.

Why the Oval Room Sessions Almost Never Happened

History is funny about Blaze Foley. Most of his tapes were lost, stolen, or literally confiscated by the DEA. The Oval Room Blaze Foley recordings represent one of those rare moments where the stars aligned—briefly—before everything went to hell again.

He recorded at the Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. Imagine that. This erratic, homeless songwriter who taped his shoes together with silver duct tape, standing in the same rooms where Aretha Franklin and The Rolling Stones tracked legendary hits. It should have been his big break. It should have made him a star.

But it didn't.

The story goes that the executive producer got caught up in a massive drug bust. The feds moved in. They seized everything. They didn't care about some Texas outlaw’s master tapes; they wanted the assets. For years, those recordings were just a rumor, a ghost story told in Austin bars like the Hole in the Wall or the Cactus Cafe.

People forget how hard it was to be Blaze.

He didn't have a permanent address. He’d sleep on a couch, or under a pool table, or literally in a tree. When he walked into a room to record, he brought all that weight with him. The "Oval Room" track itself is a biting, satirical look at the Reagan era. Blaze had this weird, deep baritone that sounded like it was coming from the bottom of a well. It was honest. Too honest for radio at the time, probably.

The Political Snarl of a Drunken Angel

"Oval Room" is a protest song. Plain and simple.

🔗 Read more: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

Blaze had a deep-seated hatred for the way the world was moving. He saw the "suits" in Austin and DC as the enemy of the working man and the artist. Honestly, he was kind of right, even if he expressed it by getting kicked out of every bar in town. He watched his friends struggle while the people in the "Oval Room"—the decision-makers—seemed totally detached from reality.

He wrote about "The President" with a sneer that you can still hear in the grainy bootlegs. It wasn't about being a Democrat or a Republican. It was about being an outsider. Blaze was the ultimate outsider. He was the guy who would walk into a fancy party and start telling everyone exactly why they were fake.

He didn't care about "networking." He cared about the truth.

The Tragedy of January 1989

You can't talk about the music without talking about the end. It’s impossible.

Blaze was shot and killed in February 1989. He was defending an elderly friend, Concho Casillas, from his own son. That’s the tragedy of Blaze Foley—he died being a "good guy" in a situation that was messy, violent, and completely avoidable. He was 39.

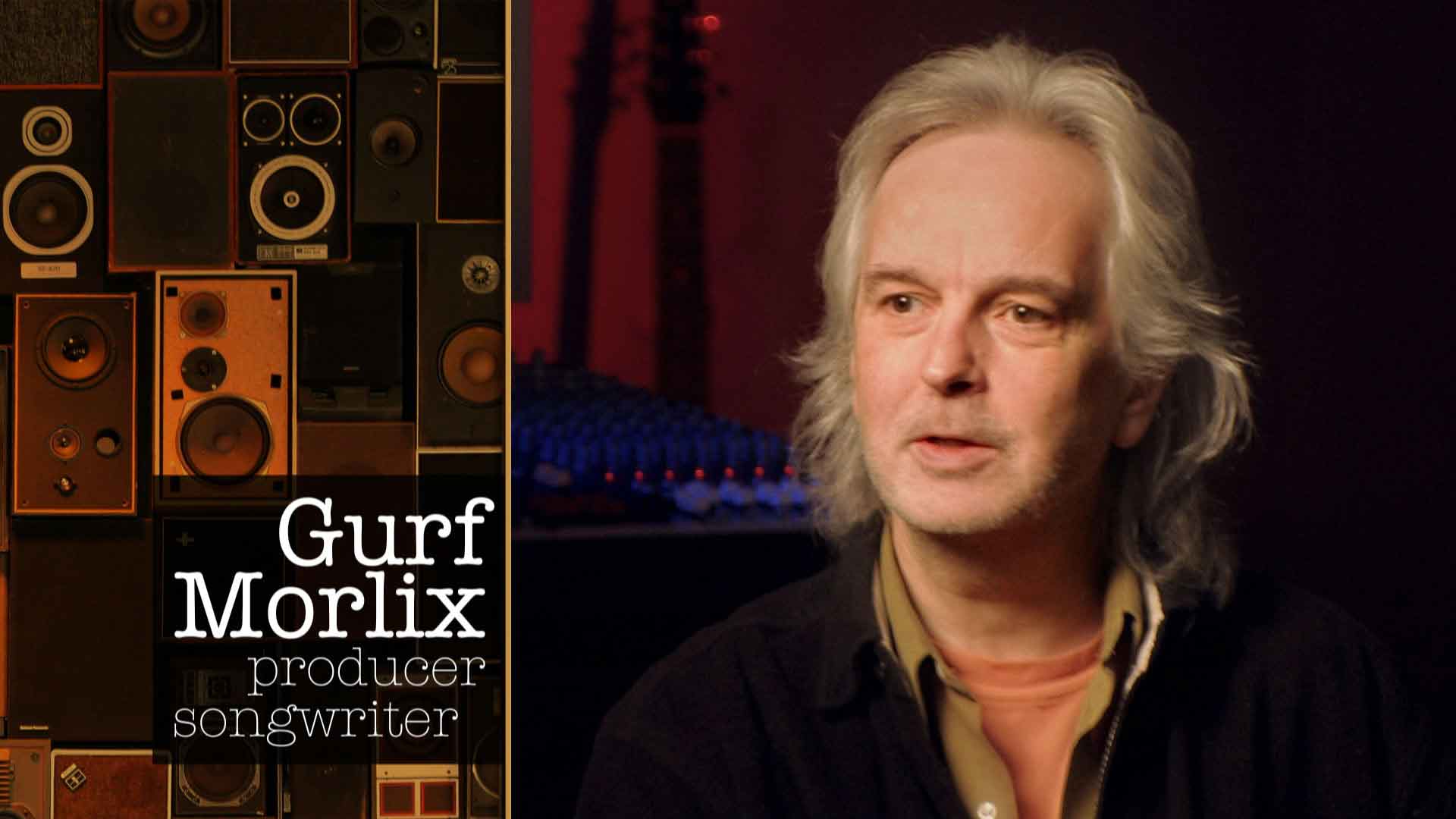

The music he left behind, including the Oval Room Blaze Foley tracks, became his only legacy. For a long time, that legacy was kept alive by just a few people. Gurf Morlix, perhaps his most loyal friend and collaborator, spent years trying to get Blaze’s music heard. Gurf was the one who actually sat in the studio with him, trying to keep him focused long enough to lay down a vocal track.

Have you ever tried to herd cats? Recording Blaze was harder.

He’d get distracted. He’d get angry. He’d get drunk. But when he hit that one note—that perfect, resonant low C—everything else vanished. The room went quiet. You realized you were in the presence of a genius who just happened to be a disaster of a human being.

The Missing Tapes and the DEA

Let's talk about the DEA bust again because it sounds like something out of a movie.

💡 You might also like: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

The album City Lights was supposed to be his masterpiece. It contained "Oval Room" and "Cold, Cold World." When the label’s owner was arrested for cocaine trafficking, the DEA didn't just take the money. They took the tapes. They were sitting in a government locker somewhere for years.

Can you imagine? Some of the best songwriting in Texas history, sitting next to bags of evidence and confiscated handguns.

Eventually, some versions surfaced. Lost tapes were found in the backs of cars. Friends had cassette dubs. This is why Blaze Foley’s discography is such a mess. You have the Live at the Austin Outhouse recordings, which are raw and gritty. Then you have the more polished studio attempts that feel like they’re trying to turn a wild animal into a house pet.

The Oval Room Blaze Foley versions we have now are a miracle of audio restoration and sheer persistence by fans who refused to let his voice die.

The Sound of Duct Tape and Heartbreak

What does it actually sound like?

It sounds like wood and smoke. Blaze’s guitar playing was deceptively simple. He used a thumb-pick and a lot of steady, alternating bass lines. It’s that "Big Bill Broonzy" influence that he never quite let go of.

In "Oval Room," the irony is thick. He’s mocking the pomp and circumstance of power while he himself is likely wearing a suit he found in a dumpster. There’s a specific kind of Texas humor in there, too. It’s dry. It’s dark. It’s the kind of humor you develop when you know you’re never going to win.

Some people compare him to Woody Guthrie. I think that’s a bit too neat. Blaze was more chaotic. Guthrie had a mission; Blaze just had a feeling. He felt everything too much. That’s why he drank. That’s why he fought. And that’s why his songs about the "Oval Room" and the political landscape of the 80s still resonate. The names of the politicians have changed, but the distance between the people in the room and the people on the street is exactly the same.

The Impact on Modern Americana

Without Blaze, you don't get a lot of the modern outlaw country scene.

📖 Related: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

Kings of Leon covered him. Ben Harper covered him. Ethan Hawke even directed a movie about him. But back when he was actually singing about the Oval Room, he was a nobody. He was a nuisance. He was the guy the cops would pick up for public intoxication and vagrancy.

It’s easy to romanticize him now. It’s harder to remember that he was a real person who suffered. He was lonely. He was often broke. When you listen to the Oval Room Blaze Foley sessions, you aren't just listening to "alt-country" or "folk." You're listening to a man who had nothing else but his songs.

He used to say he was "going to be a star," but he said it with a wink, like he knew the joke was on him. He knew the people in the Oval Room would never let him in. And honestly? He probably wouldn't have gone in even if they invited him. He would have stayed outside with the losers and the poets.

How to Listen to Blaze Foley Today

If you’re looking to dive into the Oval Room Blaze Foley catalog, don’t just grab the first "Greatest Hits" you see. You have to hunt for it.

The Sittin' by the Road collection and the Oval Room releases are the places to start. They capture that Muscle Shoals era. They show what could have been if the world hadn't gotten in the way.

- Look for the 1984 recordings. These are the ones that have that specific grit.

- Listen for the background noise. On the live tracks, you can hear the clinking of beer bottles. That’s the real Blaze Foley experience.

- Compare the versions. He’d play the same song differently every night depending on how much he’d had to drink or who was in the audience.

The "Oval Room" isn't just a song. It’s a symbol of everything Blaze stood against. It’s a reminder that the best art often comes from the people who have the least to lose.

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Fan

If you want to truly appreciate the legacy of Blaze Foley and the "Oval Room" era, here is how you should actually approach it:

- Seek out the "Lost Tapes" first. Don't go for the polished covers by famous artists. Start with the man's own voice. The Oval Room album, released long after his death, contains the heart of his political and social commentary.

- Watch the documentary 'Duct Out of Water.' It’s essential. It features the people who actually knew him—the ones who shared the "Oval Room" era with him in Austin. It strips away the myth and shows the man.

- Read 'Living in the Woods in a Tree' by Sybil Rosen. Sybil was the love of his life. Her memoir gives context to the songs that no music critic ever could. It explains why he was the way he was.

- Support local songwriters. Blaze died with nothing. The best way to honor his memory isn't just by buying his records, but by going to a dive bar and tipping the guy in the corner playing for tips. That was Blaze. That will always be Blaze.

The music of the Oval Room Blaze Foley sessions is a permanent part of the American songbook now. It doesn't matter that the DEA took the tapes or that the label went bust. The songs were too strong to stay buried. They crawled out of the evidence lockers and into the ears of anyone who ever felt like they didn't belong.

Blaze Foley didn't need an Oval Room. He just needed a guitar and someone to listen. And finally, people are listening.