You’ve probably read The Road. Maybe you’ve even braved the scalp-hunting carnage of Blood Meridian. But there’s a thinner, leaner book sitting in the middle of Cormac McCarthy’s early bibliography that makes those two look like bedtime stories.

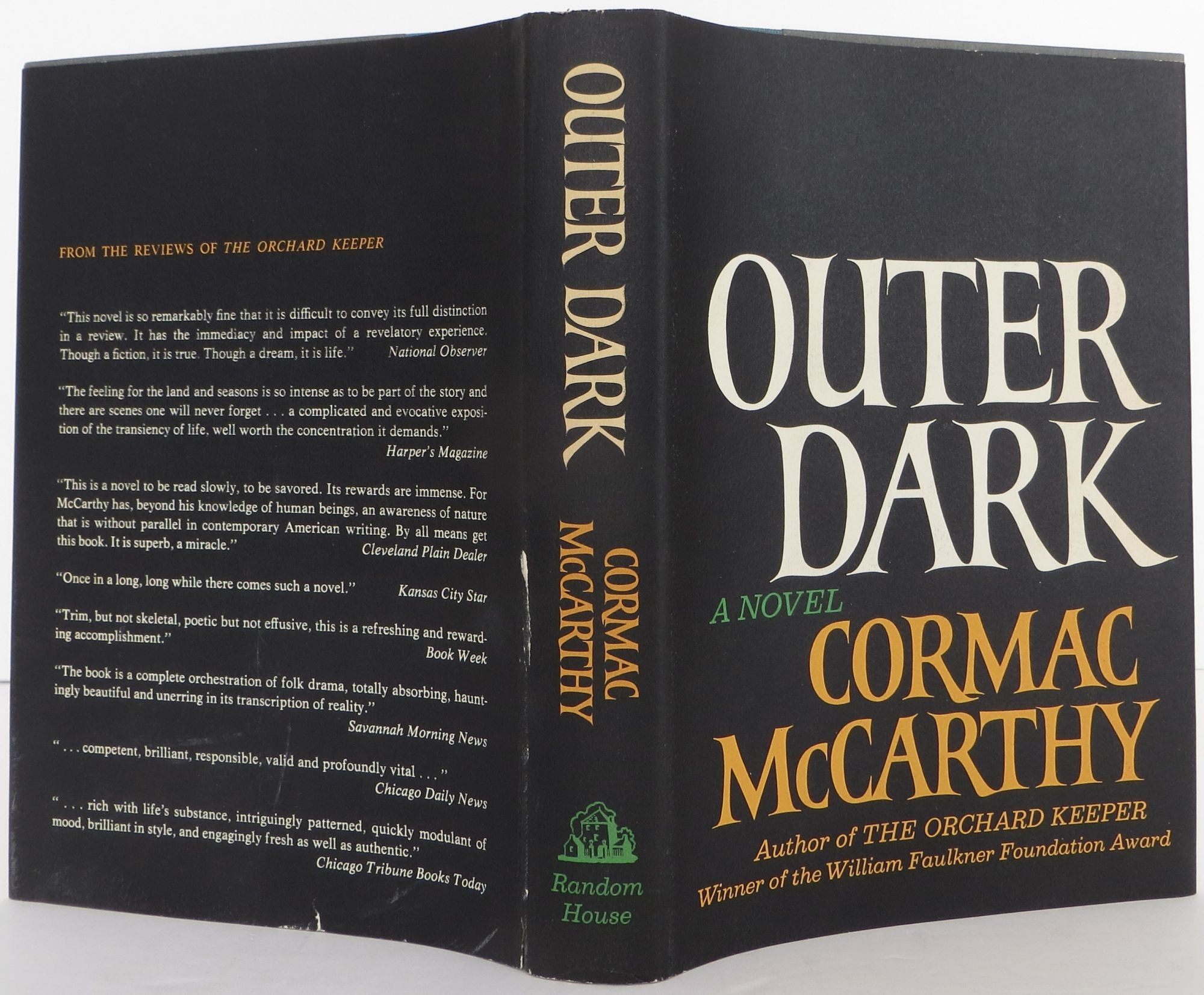

Outer Dark is basically a nightmare written in the cadence of the King James Bible. Published in 1968, it was McCarthy’s second novel, written while he was living on a Rockefeller Foundation grant in Ibiza, Spain. It’s a strange, claustrophobic story. Honestly, it’s less of a novel and more of a fever dream set in a version of Appalachia that feels like it’s located about three inches from the gates of hell.

Most people skip it. They shouldn’t.

If you’re looking for a plot that makes you feel good about humanity, look elsewhere. This isn’t that. It starts with incest and ends with something much worse. But in between, there is some of the most hauntingly beautiful prose ever put to paper.

The Plot Most People Get Wrong

People often describe Outer Dark as a simple story about a brother and sister. It isn't. It’s a story about a sin that takes on a physical, murderous shape.

Here’s the setup: Culla and Rinthy Holme are siblings living in a shack in the deep woods. Rinthy is pregnant with Culla’s child. When the baby is born, Culla takes the infant out into the woods and leaves it to die in the dirt. He tells Rinthy the baby died of natural causes and he buried it.

📖 Related: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

He lied.

Rinthy eventually finds the empty "grave" and realizes the truth. She sets out on a quest to find the child, believing a wandering tinker has taken him. Culla, haunted by a "black sun" dream and a crushing weight of guilt he won't admit to, flees in the opposite direction.

They wander through a landscape that feels like a purgatory. Rinthy is greeted with kindness by almost everyone she meets. She is an innocent. Culla, on the other hand, is followed by a "grim triune"—three nameless, murderous strangers who seem to be a manifestation of his own evil.

Why the Setting Matters

The world of Outer Dark is intentionally blurry. There are no dates. There are no maps. While the dialect screams Tennessee or the Carolina mountains, the environment is a weird mashup. One minute they are on a mountain ridge, the next they are in a swamp with "water moccasins" and "alligators."

McCarthy wasn't being lazy. He was creating a dreamscape.

👉 See also: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

This isn't historical fiction. It's an allegory. The "outer dark" refers to the biblical place of punishment, a void outside the kingdom where there is "weeping and gnashing of teeth." Culla isn't just walking across the South; he’s walking through the consequences of his own soul.

The Grim Triune: Who Are They?

The most terrifying part of the book is the three strangers. They appear in italicized chapters, moving through the countryside like a virus. They kill without reason. They eat "anonymous stew."

Some scholars think they are the Furies from Greek myth. Others say they are an inverted Holy Trinity. Honestly? They feel like the prototype for Judge Holden from Blood Meridian or Anton Chigurh from No Country for Old Men. They represent the sheer, cold indifference of the universe.

When Culla finally meets them at the end of the book, he has to watch as they do the unthinkable to his child. It’s one of the most brutal scenes in American literature. And the worst part? They don't kill Culla. They let him live.

They leave him to wander a road that ends in a "dismal swamp." No redemption. No light. Just more road.

✨ Don't miss: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

Why This Book Still Matters

You've got to appreciate how McCarthy handles Rinthy. In a lot of his later books, women are almost non-existent. But in Outer Dark, Rinthy is the heartbeat. She’s the only character with a moral center, even if that center is built on a foundation of tragedy.

Her journey is a search for love. Culla’s journey is a flight from truth.

The contrast is what makes the book work. Rinthy finds the "good" in people—farmers give her food, a lawyer gives her a place to sit. Culla finds the "bad"—he’s blamed for crimes he didn't commit, chased by mobs, and nearly drowned. The world treats you according to what you carry inside.

Actionable Insights for Readers

If you’re going to pick up a copy of Outer Dark, here is how to handle it:

- Don't read it for the plot. Read it for the atmosphere. If you try to track the logic of where they are going, you’ll get frustrated.

- Pay attention to the names. Culla and Rinthy aren't named until deep into the book. Names have power in McCarthy's world.

- Keep a dictionary handy. He uses words like "incunabular," "miasma," and "teratoid." It’s part of the spell.

- Don't look for a happy ending. There isn't one. The book is meant to be a "parable of the damned."

If you want to understand the roots of modern "grimdark" fiction or why McCarthy is considered a master of the Southern Gothic, you have to read this. It’s shorter than his later epics, but it lingers much longer.

Check your local used bookstore for the Vintage International edition. It has the best cover art and usually fits in a back pocket. Start with the first page and try not to look away.