Imagine being 23 years old and walking into a recording studio with almost nothing written. You’ve got a couple of singles under your belt, but your label wants a full LP. Now.

Basically, that’s how Otis Redding ended up at Stax Recording Studios in Memphis on July 9, 1965. What followed wasn't a weeks-long production with endless retakes and corporate oversight. It was a 24-hour sprint that somehow produced Otis Blue/Otis Redding Sings Soul, an album that didn't just top the R&B charts—it fundamentally changed how the world understood "soul" as a genre.

Honestly, the timeline is insane. Aside from the opener "Ole Man Trouble," the entire record was tracked between 10 a.m. on Saturday and 2 p.m. on Sunday. And the band even left in the middle of the night to play their own local gigs!

The Myth of the "Planned" Masterpiece

We often think of legendary albums as these carefully curated projects. You know, months of songwriting and "finding the sound." Otis Blue was the opposite. Otis arrived with only three original songs ready to go. The rest? Decided on the fly.

The house band—the legendary Booker T. & the M.G.’s—were the backbone here. You’ve got Steve Cropper on guitar, Donald "Duck" Dunn on bass, Al Jackson Jr. on drums, and Booker T. Jones on the keys. Throw in Isaac Hayes on piano and the Mar-Key horns, and you have a room full of people who could communicate through nods and rhythm.

They weren't just backing Otis; they were chasing him.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

Because the sessions were so compressed, the album has this "live" grit that most 1965 records lacked. It’s raw. It’s unpolished. You can almost hear the sweat hitting the floor during the transition in "Shake." Most soul LPs back then were just a few hits padded out with filler. Not this one. Every track feels essential, partly because there was no time to record anything that wasn't.

Taking on the Giants

One of the boldest things about Otis Blue is the tracklist. Otis decided to cover his idol, Sam Cooke, who had been killed less than a year prior.

Covering "A Change Is Gonna Come" was a massive risk. Cooke’s version was orchestral, smooth, and mournful. Otis turned it into something rugged. His voice breaks. He growls. He takes that "urbane" soul and drags it into the Georgia red clay. It’s not better or worse than Cooke’s—it’s just more human.

Then there’s the Rolling Stones cover.

When Otis recorded "(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction," he reportedly hadn't even heard the Stones' original version. He just had the lyrics. He didn't know the iconic fuzzed-out guitar riff, so the Mar-Keys just played the line on horns. It turned a rock anthem into a 90-mph soul stomp. Rumor has it the Stones actually preferred his version.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

The "Respect" Factor

Most people hear "Respect" and immediately think of Aretha Franklin. That’s fair—she owns that song now. But on Otis Blue, you hear the original blueprint.

Otis wrote it as a man coming home asking for a little recognition from his woman. It’s faster, more frantic, and way more "stomp-heavy" than Aretha’s feminist anthem. In his own words, the song took about a day to write and only 20 minutes to arrange. They nailed it in one take.

It’s kind of funny looking back. Otis was basically the King of Soul, but he often called himself a blues singer. That’s why the album has that dual title: Otis Blue for the mood, and Otis Redding Sings Soul so the marketing guys knew where to put it in the bins.

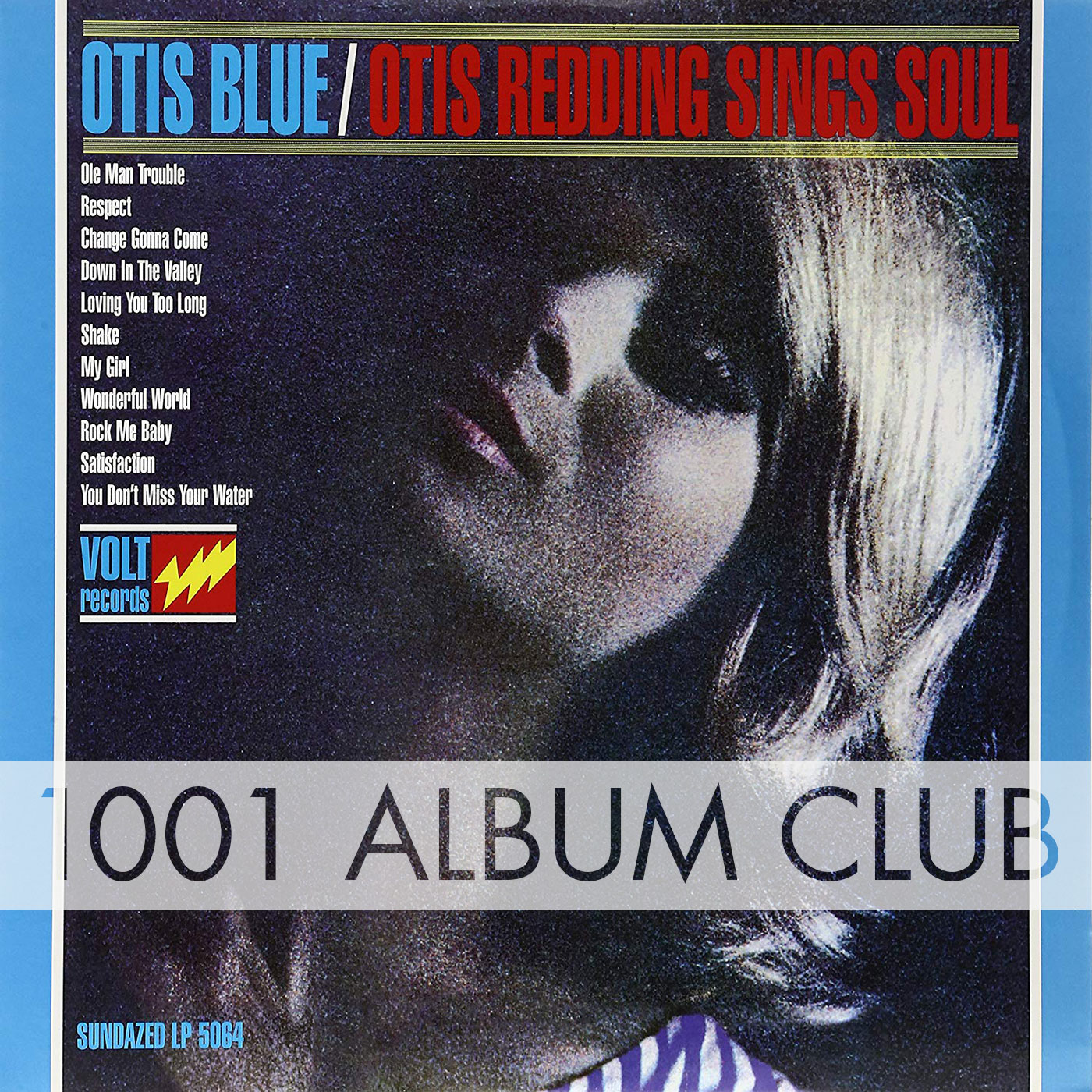

That Controversial Cover Art

If you look at the original 1965 cover, you might notice something weird. There’s a white woman on it.

The woman, often identified as German model Dagmar Dreger, had nothing to do with the music. Volt (the Stax subsidiary) put her there because they thought a "crossover" image would help the album sell to white audiences. It’s a jarring reminder of the industry’s racial dynamics in the mid-sixties.

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

Despite that, the music inside was unapologetically Black. It was the first soul album to really prove that the LP format could be an artistic statement, not just a way to sell 45s. It sold over 250,000 copies—a massive number for Stax at the time—and it turned Otis into a global superstar before his tragic death in 1967.

Why It Still Hits in 2026

We live in an era of "perfect" digital production. You can fix every flat note and nudge every drum beat into place. Otis Blue is the antidote to that.

When you listen to "I've Been Loving You Too Long," you aren't hearing a polished studio product. You’re hearing a man standing in a room in Memphis, pouring his guts out into a microphone while a band tries to keep up with his emotional intensity.

If you want to truly experience this album, here is how you should do it:

- Listen to the Mono Mix First: The stereo version from back then is "hard panned"—vocals in one ear, instruments in the other. It feels disconnected. The mono mix is where the punch is. It sounds like a single, unified wall of sound.

- Compare the Covers: Queue up the Sam Cooke originals, then the Otis versions. Notice how he changes the timing. He sings behind the beat, stretching syllables until they almost snap.

- Watch the Monterey Pop Footage: If the album hooks you, go find his 1967 Monterey Pop performance. He performs "Shake" and "Respect" from this album, and you can see the exact moment he wins over the "Love Crowd."

Otis Blue isn't just a collection of songs. It’s a 33-minute snapshot of a genius at the absolute peak of his powers, working against a clock and winning. Put it on, turn it up, and let that horn section do its work.