It is 1935. You are sitting at a kitchen table. Before you lies a square of oilcloth or a simple cardboard sheet, hand-drawn with names like "Baltic Avenue" and "Marvin Gardens." You don't know it yet, but you are looking at the original monopoly board layout, a design that would basically define the American Dream—and its frustrations—for the next century.

Most people think Charles Darrow just sat down one day and hallucinated the streets of Atlantic City into a board game. Honestly, that's the corporate myth. The reality is a lot messier, involving a Quaker woman named Elizabeth Magie, a patent for something called "The Landlord’s Game," and a community of people in Atlantic City who were playing a folk version of the game long before Parker Brothers ever touched it. The layout we know today is actually a snapshot of 1930s New Jersey real estate, frozen in time by a combination of history and a few very specific spelling errors.

The Geography of the Original Monopoly Board Layout

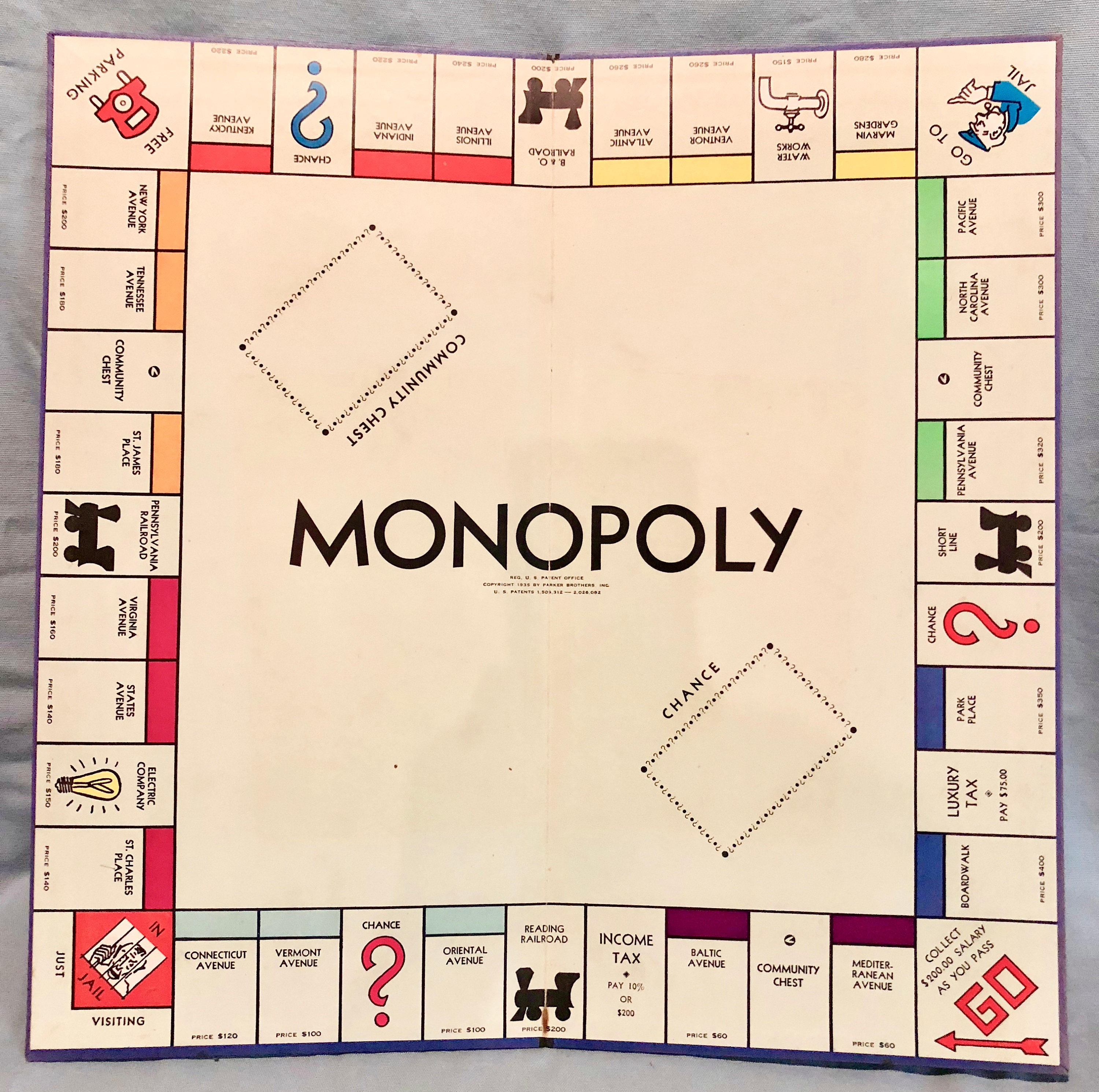

If you look at the board, it isn't random. It’s a map. The properties on the original monopoly board layout are grouped by color, but they also follow the actual geography of Atlantic City. Start at GO and move clockwise. You begin in the "slums" of the city. Mediterranean and Baltic Avenues were located in the north end, specifically the areas where the city’s Black population lived during the era of segregation. These were the cheapest spots on the board because they were the least desirable parts of the city at the time.

As you move around the first corner, things change. The light blues—Oriental, Vermont, and Connecticut—represent the transition toward the more residential and commercial sectors. But here’s a weird fact: "Oriental Avenue" isn't even a street name in Atlantic City anymore. It was renamed during a period of urban renewal. If you tried to find it today, you'd be looking for a while.

💡 You might also like: The PS4 Limited Edition Pro Consoles Worth Hunting For Today

The Weird Case of Marven Gardens

You’ve probably noticed the spelling of "Marvin Gardens" on your board at home. Or is it Marven? In the original monopoly board layout that Charles Darrow submitted to Parker Brothers, he misspelled it as "Marvin Gardens" with an "i." The actual place is Marven Gardens, a portmanteau of Margate and Ventnor, the two towns it sits between.

Parker Brothers never fixed it. For nearly a hundred years, millions of people have been playing on a board with a typo that Charles Darrow’s wife, Esther, supposedly made while helping him craft the early sets.

The layout is divided into four distinct sides, and each side has its own personality.

- The South Side: Cheap, gritty, but the easiest to develop.

- The West Side: The "bridge" properties, where things start getting expensive.

- The North Side: The middle-class struggle, featuring the orange and red groups.

- The East Side: The high-stakes, "rich" end of the board ending at Boardwalk.

The Philosophy Behind the Spaces

Why do we have four railroads? Why not three or five? The original monopoly board layout reflected the 1930s obsession with transportation. The Reading, Pennsylvania, B. & O., and Short Line railroads were the lifelines of the East Coast.

🔗 Read more: Why Transformers War for Cybertron Is Still the Gold Standard for the Franchise

Interestingly, the "Short Line" wasn't even a railroad. It was a bus line. But "Short Line Bus" didn't sound as cool as a locomotive, so the iconography stuck. The placement of the railroads at the exact midpoint of each side isn't just for aesthetics; it’s a mathematical trap. No matter where you are on the board, you are always within striking distance of a railroad. It keeps the cash flowing—usually away from you.

Free Parking and the Myth of the Jackpot

There is perhaps no space on the original monopoly board layout more misunderstood than Free Parking. In the official rules from 1935, Free Parking does absolutely nothing. It is a "rest" space.

The idea that you get a pile of tax money and fines when you land there is a "house rule" that started almost immediately. Game designers actually hate this rule. Why? Because it puts more money into the game, making it last for five hours instead of ninety minutes. The original layout was designed to be a "drain" on your resources. It was supposed to be a brutal simulation of how monopolies crush the little guy. By adding a jackpot to Free Parking, we’ve basically broken the math of the 1935 design.

How the Layout Actually Works (The Math Bit)

The orange properties (St. James Place, Tennessee Avenue, and New York Avenue) are statistically the most landed-on spots in the game. Why? Because they are exactly 6, 8, and 9 spaces away from Jail.

Since Jail is the most visited space on the original monopoly board layout, anyone coming out of the "Big House" is highly likely to land on an orange property. If you’re playing to win, you don't want Boardwalk. You want the oranges. The math of the 7-die roll (the most common outcome) dictates the flow of the game. The layout is a series of probability clusters.

🔗 Read more: Why The Cake Is A Lie Video Meme Still Haunts Gaming Culture Decades Later

- The Jail Loop: Most people spend their time between the second and third corners.

- The Dead Zone: The first corner is often skipped entirely by players jumping to the later stages of the board through Chance cards.

The Colors of the Original Monopoly Board Layout

Color coding wasn't always a thing. In Elizabeth Magie's "The Landlord’s Game," the precursor to Monopoly, the properties were mostly identified by name and value. Darrow added the color bars to make the original monopoly board layout easier to read at a glance. It was a stroke of UI (User Interface) genius before that was even a term.

The specific hues were chosen based on what was available in local print shops in Philadelphia and Atlantic City. The iconic green of the "expensive" properties and the deep blue of Boardwalk and Park Place became shorthand for wealth.

It's actually kind of funny. Boardwalk and Park Place are the only two properties in their color group. In every other group, you need three to build hotels. This makes the "Dark Blues" a high-risk, high-reward gambit. You only need two cards to start the slaughter, but landing on them is statistically rarer than landing on the Reds or Oranges.

Why We Don't Change It

Over the years, there have been hundreds of variations. You've got Star Wars Monopoly, Fortnite Monopoly, even "Cheaters Edition" Monopoly. But when people talk about "the" game, they mean the original monopoly board layout.

There is a psychological comfort in those names. Kentucky Avenue. Illinois Avenue. Atlantic Avenue. These names have survived because they represent a specific era of American urbanism. Even as Atlantic City itself went through massive changes—from a glamorous resort town to a struggling city and back again—the board remains a 1935 time capsule.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Player

If you want to respect the history of the original monopoly board layout while actually winning your next family game night, you have to look at the board through the eyes of a 1930s statistician.

- Focus on the Oranges: As mentioned, their proximity to Jail makes them the most lucrative real estate on the board.

- The Three-House Rule: Never build a hotel. The jump in rent from two houses to three is the largest in the game. Once you have three houses on a color group, you've reached the point of maximum efficiency. Plus, if you stay at three houses, you can "drain" the bank of plastic houses, preventing your opponents from building anything at all. It’s a ruthless strategy that fits the game’s original intent.

- Buy the Railroads: They are the only consistent income source that doesn't require further investment (houses/hotels). If you own all four, you're a force to be reckoned with.

- Avoid the Utilities: Honestly? Water Works and the Electric Company are usually a waste of cash. The ROI (Return on Investment) is terrible compared to a well-placed house on St. Charles Place.

The original monopoly board layout isn't just a game board. It is a piece of historical cartography that explains our relationship with money, luck, and land. Next time you pass GO, remember you're walking through a map of history—errors and all.

To dive deeper into the history, you should look up the legal battle between Parker Brothers and Ralph Anspach over the "Anti-Monopoly" game in the 1970s. It’s the only reason we even know about the game's true origins and Elizabeth Magie. Knowing the history changes the way you see every square on that board.