You just spent five bucks on a latte. Most people think that coffee cost them five dollars. It didn't.

In the real world, that coffee cost you a fractional share of an index fund, or maybe ten minutes of sleep you sacrificed to stand in line, or perhaps the apple you could’ve bought instead to actually feel healthy. This isn't just semantics. It’s the core of opportunity cost in economics, and if you aren't thinking about it daily, you’re basically flying your life’s plane with a broken altimeter.

Economists like Friedrich von Wieser—the guy who actually coined the term Opportunitätskosten—weren't just trying to make life complicated. They realized that because resources are finite, every "yes" is a "no" to something else. Choice is a trade-off. Always.

The Invisible Price Tag of Your Time

We’re obsessed with "out-of-pocket" costs. We look at a price tag and decide if the item is worth that number. But that’s amateur hour.

A professional looks at the opportunity cost.

Think about LeBron James. Should he mow his own lawn? Even if he’s the fastest lawn-mower in the world, the answer is a hard no. Why? Because the hour he spends behind a mower is an hour he isn't training, filming a commercial, or resting his body for a game where he earns tens of thousands of dollars per minute. His opportunity cost for mowing the lawn is literally thousands of dollars.

For you, it might be different. If you’re a freelance graphic designer making $75 an hour, spending three hours cleaning your house has an opportunity cost of $225. If you can hire a cleaner for $100, you’re actually losing $125 by doing it yourself.

It feels counterintuitive to spend money to save money. But the math doesn't lie.

Why Businesses Fail at Opportunity Cost

Corporate boardrooms are notorious for ignoring this. They get "tunnel vision."

👉 See also: Getting a music business degree online: What most people get wrong about the industry

Imagine a company that spends $10 million developing a new software. After two years, they realize it’s only going to return $11 million. They think, "Hey, we made a million bucks! Success!"

Wrong.

If they had put that same $10 million and two years of engineering talent into a different project that would have returned $20 million, they didn't "make" a million. They lost $9 million in potential value. This is the difference between accounting profit and economic profit. Accounting profit is what your tax guy sees. Economic profit is what the winners see.

The Sunk Cost Trap

Most people confuse opportunity cost with sunk costs. A sunk cost is money already gone—like a non-refundable movie ticket for a film that sucks.

If you sit through the movie because you "already paid for it," you’re paying twice. You paid with your money, and now you’re paying with two hours of your life that you could’ve used to grab dinner with a friend or read a book. The opportunity cost in economics tells us to ignore the past and only look at the value of the next best alternative from this moment forward.

The Formula (Sorta)

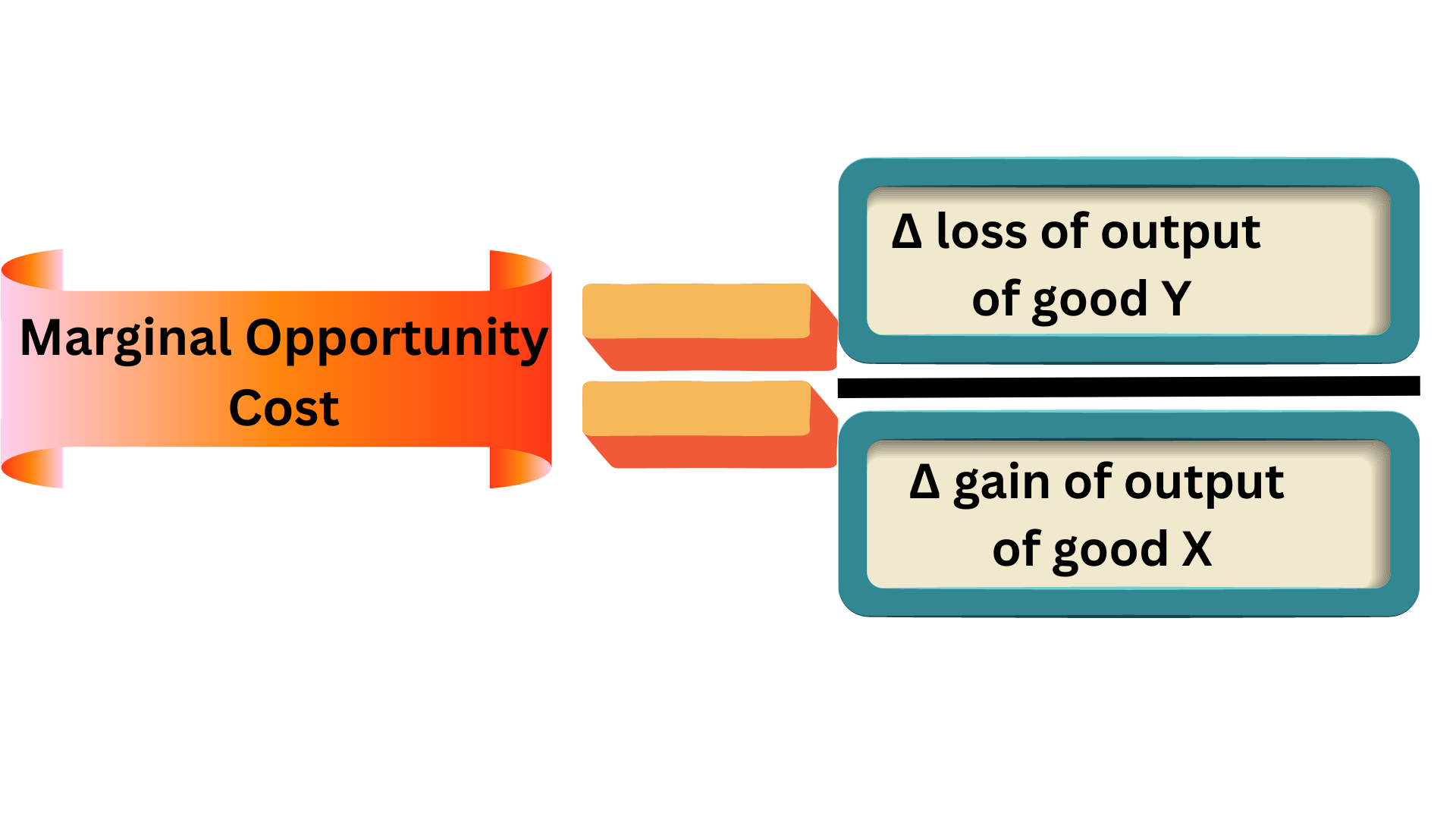

There’s a textbook way to look at this, though life is rarely as clean as a whiteboard. Generally, you’re looking at:

$Opportunity Cost = FO - CO$

In this case, $FO$ is the Return on the Best Foregone Option and $CO$ is the Return on the Chosen Option.

✨ Don't miss: We Are Legal Revolution: Why the Status Quo is Finally Breaking

But honestly? Don't get bogged down in the math. Just ask: "What am I giving up right now?"

Real-World Nuance: Education vs. The Workforce

Take the decision to get an MBA.

The tuition might be $120,000. That’s a lot. But that’s not the real cost. The real cost is the $80,000 salary you gave up for two years while you were studying. So the "economic cost" of that degree is actually $280,000 ($120k tuition + $160k lost wages).

Does the degree increase your lifetime earnings by more than $280k? If yes, it’s a good move. If no, you’re just paying for a very expensive piece of paper and some networking events.

It’s Not Always About Money

This is where people get tripped up. Opportunity cost applies to your sanity, your health, and your relationships.

- Dating: Spending six months in a "meh" relationship has a massive opportunity cost. You’re unavailable to meet the person who actually makes you happy.

- Social Media: Scrolling TikTok for two hours isn't free. It costs you the workout you didn't do or the deep work session that would have moved your career forward.

- Sleep: Staying up to finish a Netflix series has an opportunity cost of cognitive clarity the next morning.

We often choose the "low-friction" option because it's easy. But easy today usually makes tomorrow harder.

The Scarcity Reality

The reason opportunity cost in economics is a fundamental pillar—right up there with supply and demand—is scarcity. If we had infinite time and infinite money, opportunity cost wouldn't exist. You’d do everything.

But you can't.

🔗 Read more: Oil Market News Today: Why Prices Are Crashing Despite Middle East Chaos

You have roughly 4,000 weeks in a human life. Every week you spend at a job you hate is a week you aren't building something you love. That’s a high price to pay.

Actionable Steps for Better Decision Making

Stop looking at prices and start looking at trade-offs.

Audit your Tuesday. Look at your calendar. For every block of time, identify what you didn't do. If you spent three hours in a meeting that resulted in zero action items, your opportunity cost was three hours of actual productivity.

The "Hell Yes" Rule. If something isn't a "Hell Yes," it’s a "No." This is a practical application of opportunity cost. By saying no to the "okay" opportunities, you keep your resources available for the "great" ones.

Calculate your hourly rate. Even if you’re salaried, know what your time is worth. Use that number to decide if you should drive 20 minutes across town to save $5 on gas. (Hint: You shouldn't. The gas you save is worth less than the 40 minutes of your life you just burned).

Explicitly name the alternative. When making a big purchase or career move, literally write down: "By doing A, I am specifically giving up the chance to do B and C." Making the invisible visible changes how your brain processes the risk.

Economics isn't just about graphs and interest rates. It's the study of choice. When you master the concept of opportunity cost, you stop being a passive observer of your life and start becoming the architect of your time. Every choice has a ghost—the version of events that didn't happen. Start making sure the ghost isn't better than the reality.