So, you've got an API. Or maybe you're trying to connect to one. You see that field asking for an OpenAPI API key and you just want to get the code running. I get it. We’ve all been there, staring at a 401 Unauthorized error at 2 AM, wondering why the string of gibberish we pasted isn't working.

But here is the thing.

Most people treat these keys like a simple password. They aren't. Not really. An API key in the context of the OpenAPI Specification (OAS) is a specific type of credential that bridges the gap between your code and a remote server's resources. It’s the digital handshake that says, "Hey, I'm allowed to be here, and here is who is paying the bill." If you mess this up, you aren't just breaking your app; you're potentially handing over the keys to your entire cloud infrastructure or customer database.

The Messy Reality of API Keys

When we talk about an OpenAPI API key, we’re usually talking about one of two things. First, there is the actual string used to authenticate requests. Second, there is the way that key is defined inside an OpenAPI document (that YAML or JSON file formerly known as Swagger).

The specification itself—now version 3.1.0 as of the latest stable releases—is very particular about how you describe these keys. It doesn't just say "use a key." It asks where it lives. Is it in the header? The query string? A cookie? Honestly, if you're putting your keys in the query string, you’re basically shouting your password across a crowded room. Don't do that. URL logs are everywhere, and once that key is in a log file, it’s compromised.

Why standardizing matters

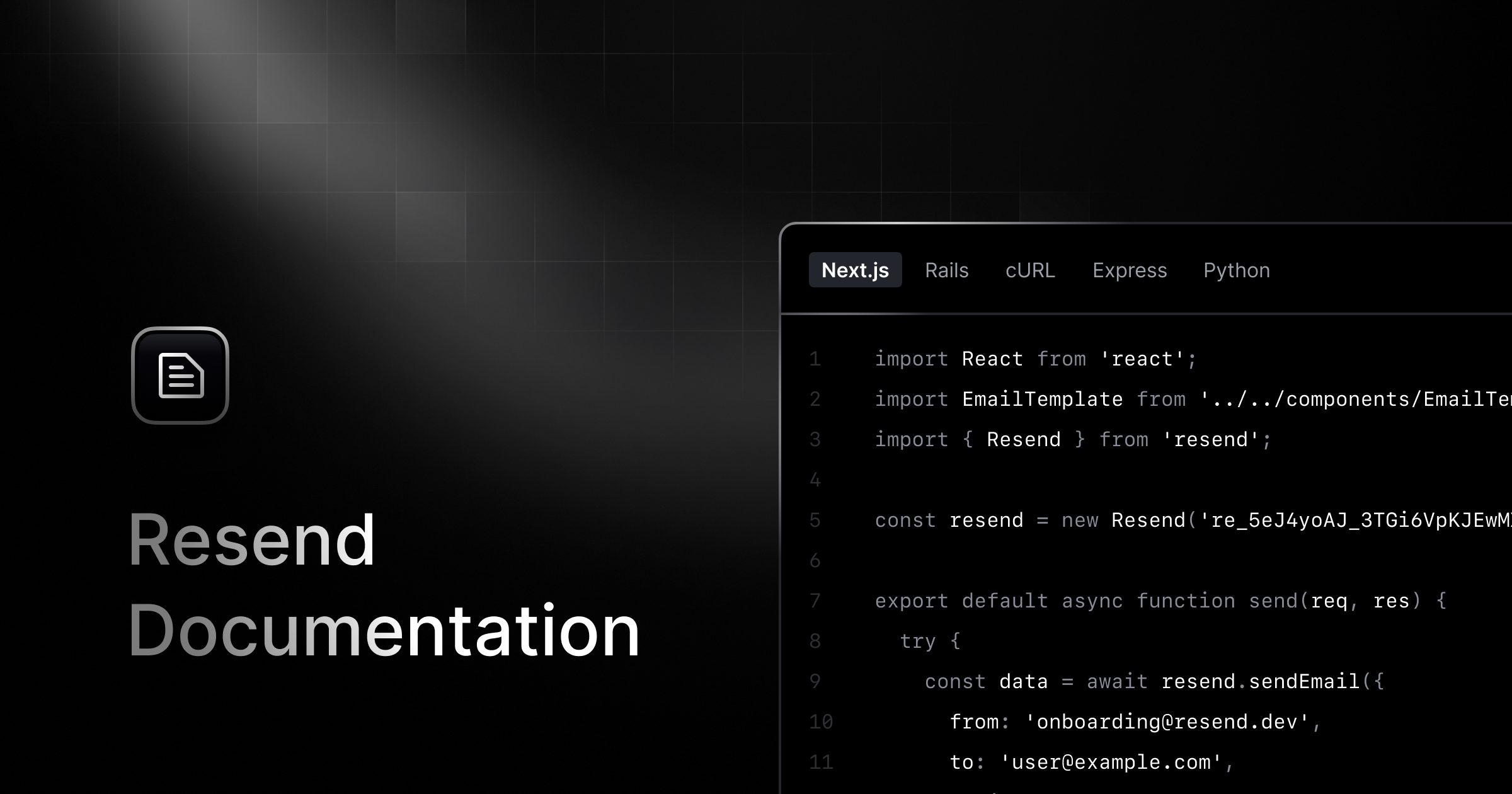

Back in the day, every dev had their own weird way of doing auth. One guy wanted it in a custom X-API-TOKEN header. Another wanted it buried in a JSON body. OpenAPI fixed this by creating a uniform way to tell tools like Postman or ReDoc exactly where to find the OpenAPI API key.

It’s about "Security Scheme Objects."

Basically, you define the security in a components section. You give it a name—let's call it ApiKeyAuth—and you tell the world it’s an apiKey type.

How to actually define the key in your Spec

Let's look at how this actually looks in a real YAML file. You can't just wing it. If the indentation is off by two spaces, the whole parser breaks and your documentation looks like garbage.

components:

securitySchemes:

MySpecialApiKey: # This is just a label

type: apiKey

in: header

name: X-API-KEY # This is the actual header name the server looks for

You've defined it. Great. But that doesn't apply it to your endpoints. You still have to go to the global level of your document or specific paths and add a security requirement. It's a two-step process.

- Define the tool.

- Use the tool.

If you forget step two, your documentation will tell users they don't need authentication, but your server will keep kicking them out. It’s a classic "it works on my machine" moment that drives frontend developers insane.

The Security Debt Nobody Talks About

We need to talk about hardcoding. Just stop.

I’ve seen enterprise-level repositories with an OpenAPI API key sitting right there in a config.js file. It’s embarrassing. Tools like TruffleHog or GitHub’s secret scanning pick these up in seconds. Hackers have scripts running 24/7 just waiting for a "commit" notification to scrape fresh keys.

Instead, use environment variables. Use a vault. Use literally anything except a plain text file.

Rotation is your friend

Keys shouldn't live forever. Think of them like milk. They go sour.

A good practice is "key rotation." You should have a system where you can generate a new OpenAPI API key and retire the old one without taking down your entire production environment. This usually involves a "grace period" where both keys work.

When API Keys Aren't Enough

Sometimes, an API key is just too weak. It’s essentially a "long-lived password." If someone steals it, they have it until you revoke it.

For high-stakes data—think healthcare or banking—you should be looking at OAuth2 or OIDC. But for a simple weather app or a CMS? A well-managed OpenAPI API key is usually fine. Just recognize the limitations. A key identifies the project or the app, but it rarely identifies the user. If you need to know exactly which human is clicking the button, a simple API key won't give you that nuance.

Common Pitfalls and How to Dodge Them

Let's get practical. You're building an integration. You've got your key. Here is where it usually goes sideways:

- Case Sensitivity: Some servers expect

x-api-key, others expectX-API-Key. OpenAPI lets you specify the exact string, so match it perfectly. - The "Bearer" Confusion: People often mix up API keys with Bearer tokens. If your security scheme is

type: httpandscheme: bearer, that is technically different from anapiKeytype in the spec. Using them interchangeably in your docs will confuse your users. - Rate Limiting: Your key is usually tied to a bucket. If you’re hitting a 429 Too Many Requests error, it’s not because your OpenAPI API key is broken; it's because you're being too chatty.

Making it Human-Friendly

If you’re the one providing the API, please, for the love of all that is holy, give your users a way to name their keys.

When I look at a dashboard and see "Key 1," "Key 2," and "Key 3," I have no idea which one is for my staging server and which one is for the production app I built three years ago. Let users add a label. Let them see the "Last Used" date. These small UI choices make the developer experience ten times better.

A Note on Public APIs

If you're using an OpenAPI API key in a client-side application—like a React app running in a browser—the key is public. Period.

Anyone can open the Network tab in Chrome and see it. If your API key allows for destructive actions (like deleting records), you cannot put it in a frontend app. You need a backend proxy. The frontend talks to your server (with its own auth), and your server talks to the third-party API using the secret key.

Implementation Steps for Success

Ready to do this right? Here is the workflow I suggest.

First, decide on the header name. X-API-KEY is standard, but Authorization is also common (though often reserved for Bearer tokens).

Second, update your OpenAPI definition. Ensure the securitySchemes are correctly mapped to your paths. Use a linter. Spectral is a great tool for this; it’ll catch if you’ve defined a security scheme but haven't actually applied it anywhere.

Third, set up a local .env file. Put your OpenAPI API key in there and add .env to your .gitignore. This is the single most important step for your sanity and security.

Finally, test the documentation. If you're using Swagger UI, click the little "Authorize" padlock icon. Paste your key. Try an endpoint. If it works there, it’ll work for your users.

📖 Related: Why iPhone 14 Pro Gold Still Matters in 2026

Moving Forward

Security isn't a "set it and forget it" thing. It's a process.

As you scale, you might find that simple keys don't cut it anymore. You might need scoped keys—keys that can only read but not write, or keys that only work from certain IP addresses. The OpenAPI Specification supports these nuances through multiple security objects and scopes.

The best thing you can do right now? Go check your main repo. Search for "key" or "secret." If you find a hardcoded OpenAPI API key staring back at you in plain text, move it to an environment variable immediately. Your future self (and your security team) will thank you.

Once that's cleared up, look into implementing a usage dashboard so you can see who is using which key and why. Observability is the only way to catch an abnormality before it becomes a headline. Stay safe out there, keep your headers clean, and always, always validate your YAML before you push.