You’re sitting at a dimly lit bar. The air smells like stale hops and wood polish. You lean over the scuffed mahogany and say it. "One whiskey, one bourbon, one beer." It’s more than just a drink order; it’s a rhythmic demand for a reset. Most people think George Thorogood wrote it. He didn't. This song has a history that stretches back through decades of American blues and R&B, surviving on the grit of storytellers who knew exactly what it felt like to be broke, homeless, and thirsty.

Music is weird like that. A song can travel through three different artists, changing its skin every time, until it becomes a permanent part of the cultural lexicon.

Where One Whiskey One Bourbon One Beer Actually Started

The year was 1953. Amos Milburn, a jump blues pianist with a voice like smooth velvet, released "One Scotch, One Bourbon, One Beer." Written by Rudy Toombs, it wasn't exactly the hard-rocking anthem we know today. It was a mid-tempo swing. Milburn was the king of "drinking songs" in the early fifties, having already hit it big with tracks like "Bad, Bad Whiskey."

The lyrics tell a simple, painful story. A man is at a bar. He's got problems. He wants to drown them. Honestly, the original version is almost polite compared to what came later. Milburn’s protagonist is trying to find a way to forget a woman, and he's doing it with a selection of spirits that would give a modern mixologist a panic attack.

Then came John Lee Hooker.

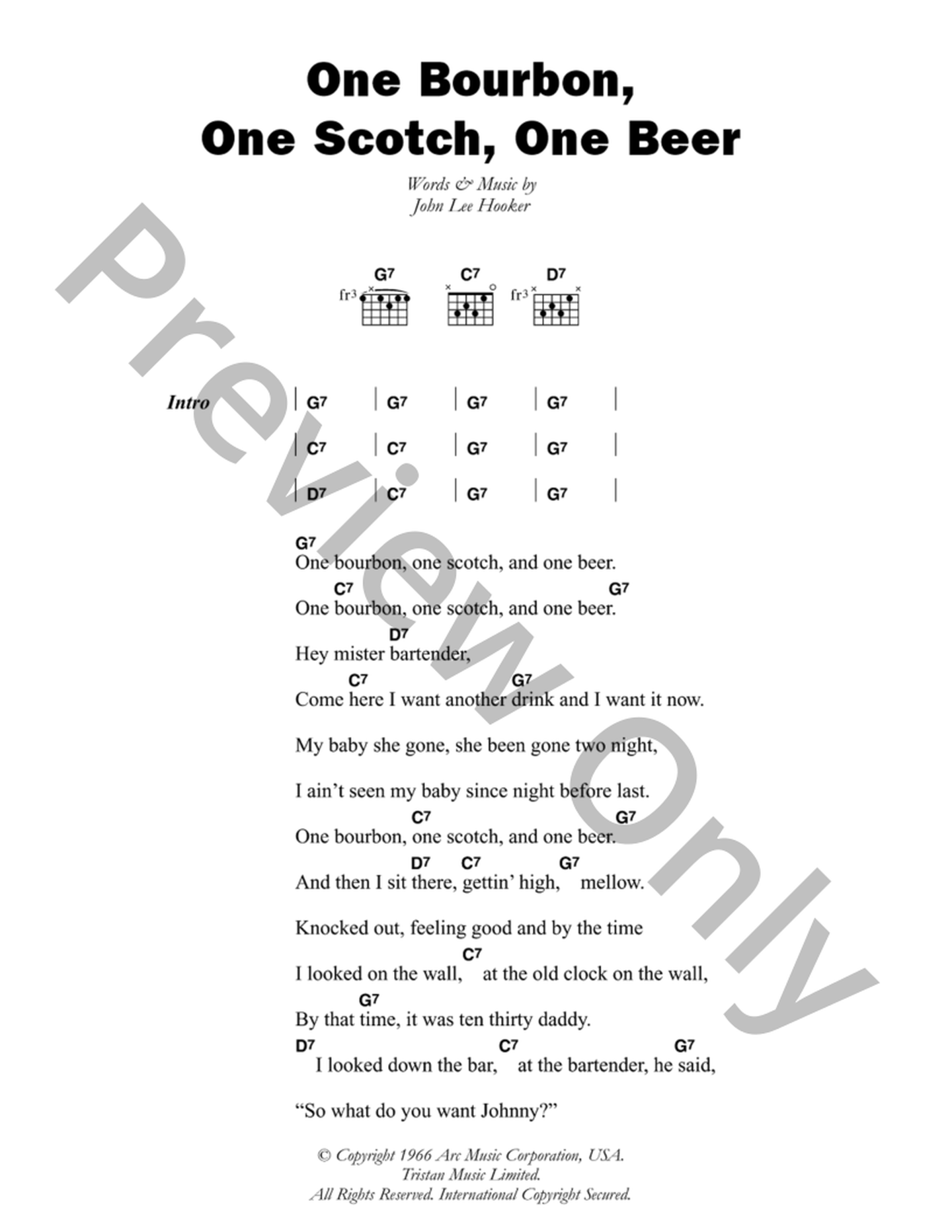

If Milburn gave the song its bones, Hooker gave it its soul—and its darkness. In 1966, John Lee Hooker recorded his version, titled "One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer." He flipped the order. He added the narrative. That long, rambling, spoken-word intro about being behind on the rent and getting kicked out by a landlord who "wasn't no good" turned a catchy tune into a cinematic masterpiece of the blues. Hooker's guitar stomps. It doesn't just play notes; it marches.

The Thorogood Transformation

By the time George Thorogood and the Delaware Destroyers got their hands on it in 1977, the song was ready to explode. Thorogood did something brilliant. He took the "House Rent Boogie" narrative from John Lee Hooker and stitched it directly onto the "One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer" framework.

💡 You might also like: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

He also simplified the order to one whiskey one bourbon one beer.

Why does this version stick? It’s the attitude. Thorogood plays the part of the lovable loser perfectly. You can almost see the landlord knocking on the door while George hides under the bed. When he finally makes it to the bar at "a quarter to ten," the sense of relief is palpable. It’s a blue-collar anthem because it treats the bar as a sanctuary. A place where the clock doesn't matter, even if the bartender is trying to close up.

The Anatomy of the Order

Let's talk about the drinks themselves. This isn't a cocktail flight at a speakeasy in Brooklyn. This is a suicide mission for your liver.

- The Whiskey: Usually implies a rye or a generic blended whiskey in the context of the 1950s. It’s the sharp, biting start.

- The Bourbon: Sweeter, heavier, corn-based. It’s the American heart of the order.

- The Beer: The chaser. The long drink. The thing that keeps you hydrated while the spirits do the heavy lifting.

Mixing these three is a recipe for a legendary hangover. But in the song, it's a symbolic gesture. You aren't drinking for the notes of vanilla or the "mouthfeel." You're drinking to reach a destination.

Why the Song Still Dominates Jukeboxes

People love a tragedy they can dance to. The narrative of being fired from a job and having a landlord who has "no heart at all" is universal. Even in 2026, the struggle to make rent is a real thing. When Thorogood growls about his "lifestyle" being in jeopardy, he’s speaking for every person who has ever felt the squeeze of the economy.

Musically, it’s a masterclass in tension and release. The song stays on one chord for an incredibly long time. That’s a classic blues trick. It builds a sense of monotony and frustration—just like a boring job or a long day—until the chorus hits. When the chorus finally breaks through, it feels like a physical weight lifting off your shoulders.

📖 Related: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

Interestingly, John Lee Hooker actually liked Thorogood's version. He saw it as a way for the blues to reach a younger, whiter, louder audience. It worked.

Misconceptions and Barroom Debates

One of the biggest arguments people have over their third pint is whether the song is about three separate drinks or a specific way of ordering. Some purists argue that you’re supposed to drink them in a specific sequence. Others say it’s just a "Boilermaker" with an extra shot.

The truth is found in the lyrics. The protagonist is trying to get as much alcohol as possible before the "stop clock" hits. It’s about urgency.

- The Scotch vs. Whiskey Debate: Milburn and Hooker both mentioned Scotch. Thorogood went with "Whiskey." Scotch was seen as a bit more "uptown" in the mid-century. General whiskey felt more "pool hall."

- The Rent Context: In Hooker’s version, the landlord is a woman. In Thorogood’s, the landlord is a "he." Both are equally ruthless.

- The Timeline: The song spans roughly 25 years of evolution before it reached its final "radio" form.

How to Listen (And Drink) Responsibly

If you’re going to appreciate one whiskey one bourbon one beer, you have to do it right. Don't listen to it on tinny smartphone speakers. This song requires bass. It requires a bit of grit.

If you're actually at a bar and decide to order the "Thorogood Special," warn your bartender. It’s a lot of liquid. Most modern bartenders will give you a look that says "I know exactly what song you were listening to on the way here."

Expert Insight: The Cultural Impact

Musicologist Ted Gioia has often noted how the blues functions as a cathartic tool. This song is the epitome of that. It doesn't offer a solution to the man's problems. He still doesn't have a job at the end of the track. He still doesn't have a place to stay. But for those eight minutes and twenty-six seconds (on the Move It on Over album), he has the floor. He has our attention.

👉 See also: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

The song bridges the gap between the 1940s jump blues and the 1970s arena rock. That’s a massive span. It proves that the "three drinks" motif is one of the most durable tropes in American songwriting.

Actionable Steps for the Modern Listener

You don't need to lose your job to appreciate the history of this track.

First, go back and listen to Amos Milburn’s 1953 original. Notice the piano work. It’s incredible. It’s sophisticated. It’s "drinking clothes" music.

Second, find a live recording of John Lee Hooker performing the song. He often improvised the dialogue. Every performance was a slightly different story about a different landlord. It turns the song into a living, breathing piece of oral history.

Finally, check your local dive bar's jukebox. If one whiskey one bourbon one beer isn't on there, you're in the wrong bar.

When you're looking for the song on streaming services, remember the slight title variations. Searching for "One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer" will usually get you the Hooker and Thorogood versions, while the Milburn version often hides under "One Scotch, One Bourbon, One Beer."

The next time you're stressed about work or the bills are piling up, put on the Thorogood version. Turn it up until the windows rattle. It won't pay your rent, but it'll make the situation a lot easier to handle for a few minutes.

Just make sure you have a ride home.